NCAA News Archive - 2007

« back to 2007 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Transfer data to guide future decisions

|

By Michelle Brutlag Hosick

The NCAA News

The NCAA News

Conventional wisdom dictates that to succeed academically and ultimately graduate, a student must stay in school. But does it have to be the same school?

A new study shines some light on that question and will help NCAA committees and working groups charged with developing policy to improve academic performance complete their work.

In 2002, when a working group of the Division I Board of Directors began thinking about improving the academic performance of student-athletes, members had an inkling that student-athletes — and students overall — who stayed at one institution for their entire collegiate career were more likely to graduate, graduate on time and perform better academically.

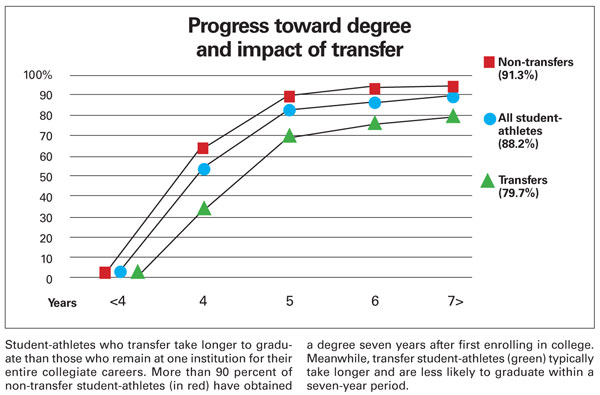

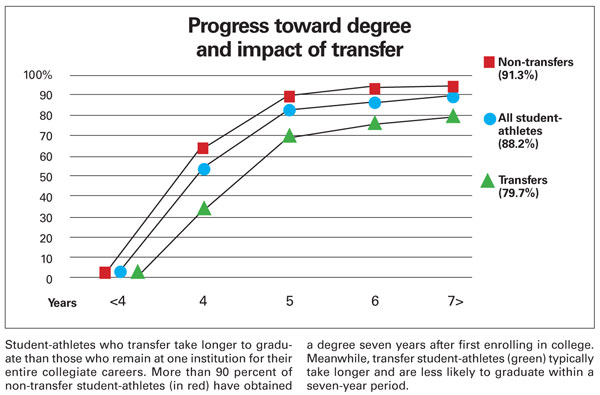

Five years later, and three years into the Academic Performance Program designed by the Committee on Academic Performance, data indeed indicate that student-athletes who transfer from one institution to another do have a lower probability of degree completion and take longer to complete the bachelor’s degree than those who remain at the institution at which they first matriculated.

The study conducted by the NCAA research staff and University of Southern California professor Jack McArdle also includes information about the impact transfer student-athletes have on team academic performance.

The research revealed that the conferences with the most incoming transfers often have the lowest Academic Progress Rates. And some of the sports with the lowest APRs — men’s basketball and baseball — have the highest number of transfer student-athletes. In those two sports in fact, more than a quarter of student-athletes have transferred into an institution, most from two-year schools. Previous research has shown that transfers from two-year institutions to four-year institutions do not perform as well academically.

The research also shows that the Football Bowl Subdivision conferences actually have fewer student-athletes transferring into their institutions, contrary to the prevailing belief that some Football Championship Subdivision schools serve as stepping stones for student-athletes looking to move to larger athletics programs.

Because tracking transfers from an institution is more difficult than monitoring incoming transfers, NCAA researchers framed the study by assuming that students leaving an institution academically eligible transferred and those leaving ineligible did not.

The data showed the rate of “transfer-out” student-athletes did not vary dramatically among conferences, while there were significant differences among leagues in incoming transfers (since some conferences tend to attract transfers from two-year institutions more than others). Baseball and men’s and women’s basketball had the highest by-sport transfer rates.

The information already has helped the Division I Baseball Academic Enhancement Working Group develop recommendations to improve the academic culture in baseball.

The study also should assist other groups as they study ways to improve academic performance of student-athletes. Those groups include CAP, the newly formed Division I Basketball Academic Enhancement Working Group, and a working group of the Academics/Eligibility/Compliance Cabinet formed to consider transfer issues in the wake of legislation requiring student-athletes to be academically eligible at their current institution before transferring and receiving financial aid at another school.

As CAP embarks on a discussion about the importance of retention to the APR, for example, data indicating the future academic success of student-athletes who transfer will be crucial. Many coaches and athletics administrators argue their programs should not be penalized for student-athletes who leave their institutions in good academic standing. CAP Chair Walter Harrison, president of the University of Hartford, finds merit in some of those arguments, but he favors retaining retention as part of the APR formula.

“When you look at specific student-athlete populations, you do see that in some instances, when you transfer, you do not succeed academically,” Harrison said.

CAP began an initial examination of the transfer data at its April meeting and will continue to discuss retention and its impact on the APR at future meetings.

APR is meant to be a real-time snapshot of the progress toward graduation for student-athletes on a particular team. Early data show that eliminating retention from the formula would significantly impact its ability to predict the future graduation success of student-athletes. Harrison welcomes the new data to help make decisions that are in student-athletes’ best interests.

“In the end, that’s what the whole academic performance program is about. It’s what’s best for the student-athlete, not what’s best for the university or the won-lost record of a particular team,” Harrison said. “We want to be careful before we discard part of the formula, but if it turns out that upon closer examination that something else is a better predictor of graduation, all of us are willing to look at that.”

As a member of the baseball working group, Harrison said the transfer rate was a particular concern in that sport; hence the recommendation, and later Board adoption of legislation requiring baseball student-athletes to serve a year in residence after transferring, just as basketball and football student-athletes do.

Also a member of the basketball working group, Harrison predicted that the data also would help inform decisions in that sport, though he suspected it might be different than in baseball, which is affected by the timing and structure of the professional draft.

The basketball group is scheduled to begin meetings next month.

The Transfer Issues Ad Hoc Working Group of the AEC Cabinet will also use the data in its review of NCAA transfer policies. Working group member Warde Manuel, athletics director at University at Buffalo, the State University of New York, said the study will help his group understand the academic impact of transferring and lead to a consistent policy that is best for student-athletes.

He said while he wasn’t surprised that it took longer for student-athletes who transferred to graduate, he did not expect the overall graduation rates to decline for student-athletes who transferred.

“Most people would say transferring is good because it helps the student — it gets them into a better position, leaving a bad situation or getting closer to home, for whatever reason they transfer,” Manual said. “The data were a little surprising in that those students who transfer showed a decline in graduation.”

It’s clear that the data culled from this study will be useful to the Association as it refines its approach to academic reform, both overall and within specific sports. Each group will study the intricacies of the impact of transferring on various subsets of the student-athlete population with an eye toward forming the best policy for student-athletes.

A new study shines some light on that question and will help NCAA committees and working groups charged with developing policy to improve academic performance complete their work.

In 2002, when a working group of the Division I Board of Directors began thinking about improving the academic performance of student-athletes, members had an inkling that student-athletes — and students overall — who stayed at one institution for their entire collegiate career were more likely to graduate, graduate on time and perform better academically.

Five years later, and three years into the Academic Performance Program designed by the Committee on Academic Performance, data indeed indicate that student-athletes who transfer from one institution to another do have a lower probability of degree completion and take longer to complete the bachelor’s degree than those who remain at the institution at which they first matriculated.

The study conducted by the NCAA research staff and University of Southern California professor Jack McArdle also includes information about the impact transfer student-athletes have on team academic performance.

The research revealed that the conferences with the most incoming transfers often have the lowest Academic Progress Rates. And some of the sports with the lowest APRs — men’s basketball and baseball — have the highest number of transfer student-athletes. In those two sports in fact, more than a quarter of student-athletes have transferred into an institution, most from two-year schools. Previous research has shown that transfers from two-year institutions to four-year institutions do not perform as well academically.

The research also shows that the Football Bowl Subdivision conferences actually have fewer student-athletes transferring into their institutions, contrary to the prevailing belief that some Football Championship Subdivision schools serve as stepping stones for student-athletes looking to move to larger athletics programs.

Because tracking transfers from an institution is more difficult than monitoring incoming transfers, NCAA researchers framed the study by assuming that students leaving an institution academically eligible transferred and those leaving ineligible did not.

The data showed the rate of “transfer-out” student-athletes did not vary dramatically among conferences, while there were significant differences among leagues in incoming transfers (since some conferences tend to attract transfers from two-year institutions more than others). Baseball and men’s and women’s basketball had the highest by-sport transfer rates.

The information already has helped the Division I Baseball Academic Enhancement Working Group develop recommendations to improve the academic culture in baseball.

The study also should assist other groups as they study ways to improve academic performance of student-athletes. Those groups include CAP, the newly formed Division I Basketball Academic Enhancement Working Group, and a working group of the Academics/Eligibility/Compliance Cabinet formed to consider transfer issues in the wake of legislation requiring student-athletes to be academically eligible at their current institution before transferring and receiving financial aid at another school.

As CAP embarks on a discussion about the importance of retention to the APR, for example, data indicating the future academic success of student-athletes who transfer will be crucial. Many coaches and athletics administrators argue their programs should not be penalized for student-athletes who leave their institutions in good academic standing. CAP Chair Walter Harrison, president of the University of Hartford, finds merit in some of those arguments, but he favors retaining retention as part of the APR formula.

“When you look at specific student-athlete populations, you do see that in some instances, when you transfer, you do not succeed academically,” Harrison said.

CAP began an initial examination of the transfer data at its April meeting and will continue to discuss retention and its impact on the APR at future meetings.

APR is meant to be a real-time snapshot of the progress toward graduation for student-athletes on a particular team. Early data show that eliminating retention from the formula would significantly impact its ability to predict the future graduation success of student-athletes. Harrison welcomes the new data to help make decisions that are in student-athletes’ best interests.

“In the end, that’s what the whole academic performance program is about. It’s what’s best for the student-athlete, not what’s best for the university or the won-lost record of a particular team,” Harrison said. “We want to be careful before we discard part of the formula, but if it turns out that upon closer examination that something else is a better predictor of graduation, all of us are willing to look at that.”

As a member of the baseball working group, Harrison said the transfer rate was a particular concern in that sport; hence the recommendation, and later Board adoption of legislation requiring baseball student-athletes to serve a year in residence after transferring, just as basketball and football student-athletes do.

Also a member of the basketball working group, Harrison predicted that the data also would help inform decisions in that sport, though he suspected it might be different than in baseball, which is affected by the timing and structure of the professional draft.

The basketball group is scheduled to begin meetings next month.

The Transfer Issues Ad Hoc Working Group of the AEC Cabinet will also use the data in its review of NCAA transfer policies. Working group member Warde Manuel, athletics director at University at Buffalo, the State University of New York, said the study will help his group understand the academic impact of transferring and lead to a consistent policy that is best for student-athletes.

He said while he wasn’t surprised that it took longer for student-athletes who transferred to graduate, he did not expect the overall graduation rates to decline for student-athletes who transferred.

“Most people would say transferring is good because it helps the student — it gets them into a better position, leaving a bad situation or getting closer to home, for whatever reason they transfer,” Manual said. “The data were a little surprising in that those students who transfer showed a decline in graduation.”

It’s clear that the data culled from this study will be useful to the Association as it refines its approach to academic reform, both overall and within specific sports. Each group will study the intricacies of the impact of transferring on various subsets of the student-athlete population with an eye toward forming the best policy for student-athletes.

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy