NCAA News Archive - 2007

« back to 2007 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Three for all

Once-controversial long-range shot works way into basketball culture

Once-controversial long-range shot works way into basketball culture

|

By Greg Johnson

The NCAA News

The NCAA News

Nineteen feet, nine inches.

That is the distance of the three-point line, which some people consider among the most significant innovations in college basketball.

Its adoption for the 1986-87 season was a defining moment for the sport, if not for the NCAA.

The three-pointer is taken for granted as part of today’s game, but 20 years ago it was as controversial as changing the ball from round to square.

Starting in 1980, conferences began experimenting with the shot from varying distances before it was decided that 19 feet, nine inches, was the best distance for the college game.

The three-pointer can help underdogs stay with a more powerful team and can create stirring comebacks. But the concept had its critics before it became a fixture in the game.

“You want to know why it wasn’t popular? It’s because no one knew how to defend it,” said basketball analyst Nancy Lieberman. “If you are not comfortable, sometimes you don’t want something new. If you ask the same coaches who were against it when it was put in what they feel about it now, they would probably be totally different. That’s because they’ve played it and have used it to their advantage.”

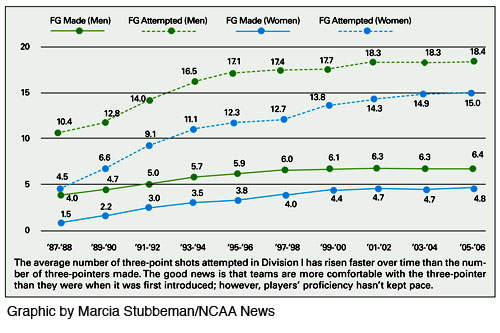

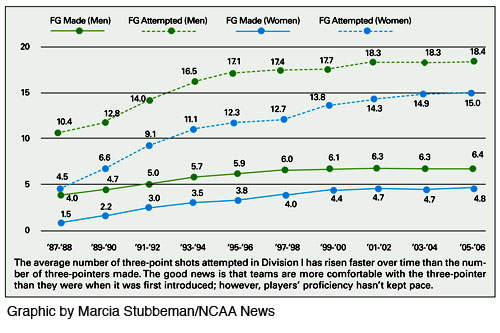

In the first year of the rule, Division I men’s basketball teams averaged 3.5 three-point field goals on 9.2 attempts. The 38.4 percent shooting percentage remains the highest for Division I men. Last year’s numbers were an all-time high 6.4 made of an also all-time high 18.4 attempted. The shooting percentage for the 2005-06 season was 35 percent, the highest since 1992-93.

Women’s teams, which adopted the rule a year after the men, averaged just 1.5 three-pointers in 4.5 attempts the first year, steadily increasing to the all-time highs of 4.8 of 15 last season. Shooting percentages have hovered between the low of 30.8 in 1995-96 to the all-time high of 34.1 in 1988-89 (though the average attempts were just 5.5 that year).

The three-pointer not only changed the way the game was scored, but also the game’s tactics and strategies.

“Help-side defense was the staple of what everyone played before the three-point shot,” said West Virginia University men’s coach John Beilein. “You pressured the ball and there were always four guys waiting to help. With the three-point shot, if someone is waiting to help you can drive and kick the ball out to a shooter. Now, you are giving up three points.”

Officials also had to adjust their mechanics.

“You have to watch the feet, the contact and then any fouls after the shot,” said Marcy Weston, former NCAA women’s basketball rules secretary and officiating coordinator. “You have to get your sequence down about what you are looking for. People coming in the game now start with that, but before you didn’t have to watch where people’s feet were.”

Like most new rules, the three-pointer required an adjustment period. Many coaches had designated players who had the green light to shoot behind the arc.

Like most new rules, the three-pointer required an adjustment period. Many coaches had designated players who had the green light to shoot behind the arc.

The first Division I men’s championship game under the new rule is a good example. Indiana University, Bloomington, defeated Syracuse University, 74-73, and the Hoosiers attempted just 11 three-pointers. But all-American guard Steve Alford was the designated shooter, hitting 7-of-10. Syracuse took only 10 three-point shots, all from guards Sherman Douglas and Greg Monroe.

Compare that to the 2005 title game between the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the University of Illinois, Champaign. North Carolina prevailed, 75-70, relying on the inside play of Sean May and an efficient 9-of-16 from three-point range. Illinois was the more perimeter-oriented team, finishing the game 12-of-40 from beyond the arc.

The three-point shot has become less of a specialty over time. Beilein, who has coached at West Virginia since 2002, is known for having multiple three-point threats on the court at all times.

“My teams have always recruited shooters even before the three-point line,” Beilein said. “After the rule change, it made it even more important to recruit shooters. I don’t think shooting was something people recruited as much. People were looking for more athleticism, quickness and defense then.”

He coached at Division II Le Moyne College when he inherited Len Rauch, an inside player with the versatility to make the three-point shot. When he took the head coaching job at Canisius University in 1992, he inherited another good shooting post player in Michael Meeks.

Then when he went to West Virgina, 6-11 center Kevin Pittsnogle was already on campus. His skills fit right in with Beilein’s system. Pittsnogle made 253 career three-pointers while shooting 41 percent.

“We ran a flex or a box-type of offense until the rule change,” Beilein said. “Then we started to spread the floor. If a kid can really shoot, he is a higher level of recruit for us. If he has the ability to make shots from the perimeter and is a big kid, the better it is for us.”

Effect on women’s game

The national trends on frequency and average number of three-pointers made at the Division I level have increased gradually through the years. Only once, in 2003-04, has the average number made been lower than the previous year.

“It was really accepted whole-heartedly, because the men had already done it,” said Weston, the senior woman administrator at Central Michigan University. “The dunk isn’t as prevalent in the women’s game, so the three-point shot added an element of excitement.”

The women’s game adopted the shot clock before the men to increase the pace of the game, and the three-pointer has continued to expand scoring.

“It opened up the game, because it allowed the post players to have a little more working room down on the box,” Lieberman said. “We can see their skills, and it makes teams make choices about whether they should double team.”

Bill Fennelly, the head women’s basketball coach at Iowa State University, heard from critics when the three-point rule entered the game.

“A lot of people thought it was a fluke or a trick shot,” Fennelly said. “The traditionalists out there couldn’t figure out why we were awarding more points for a basket because it was from farther away. For something that changed the game as dramatically as it did, there were a lot of people at the time who felt it wasn’t necessary.”

Fennelly was coaching at the University of Toledo and immediately embraced the new rule. He estimates his team attempted 30 three-point shots in the first game with the new rule.

Since he’s been at Iowa State, the three-point shot has become a significant marketing tool for his program.

“You have the loud public address announcement when someone makes one,” Fennelly said. “T-shirts get thrown to the crowd. It has dramatically changed the game. Our game is built on finesse, skill, passing and shooting. Maybe it is not as rugged and as athletic as the men’s game. But it allows someone with the skill set to shoot the ball and be a great part of what the game is about.”

While the line hasn’t moved in 20 years, some people favor a longer shot. The international distance, for example, is 20 feet, 6 inches. The NCAA has experimented with that arc but has not garnered enough momentum for a permanent change. The closest consideration came two years ago when a proposal packaged the longer three-pointer with a wider free-throw lane. Rules committees at that time agreed to leave the court markings alone until at least the 2007-08 season.

“I’m not a proponent of moving the line back, only because I don’t think anything is broken,” Beilein said. “The three-pointer and the shot clock have been ingenious as far as adding excitement to college basketball.”

That is the distance of the three-point line, which some people consider among the most significant innovations in college basketball.

Its adoption for the 1986-87 season was a defining moment for the sport, if not for the NCAA.

The three-pointer is taken for granted as part of today’s game, but 20 years ago it was as controversial as changing the ball from round to square.

Starting in 1980, conferences began experimenting with the shot from varying distances before it was decided that 19 feet, nine inches, was the best distance for the college game.

The three-pointer can help underdogs stay with a more powerful team and can create stirring comebacks. But the concept had its critics before it became a fixture in the game.

“You want to know why it wasn’t popular? It’s because no one knew how to defend it,” said basketball analyst Nancy Lieberman. “If you are not comfortable, sometimes you don’t want something new. If you ask the same coaches who were against it when it was put in what they feel about it now, they would probably be totally different. That’s because they’ve played it and have used it to their advantage.”

In the first year of the rule, Division I men’s basketball teams averaged 3.5 three-point field goals on 9.2 attempts. The 38.4 percent shooting percentage remains the highest for Division I men. Last year’s numbers were an all-time high 6.4 made of an also all-time high 18.4 attempted. The shooting percentage for the 2005-06 season was 35 percent, the highest since 1992-93.

Women’s teams, which adopted the rule a year after the men, averaged just 1.5 three-pointers in 4.5 attempts the first year, steadily increasing to the all-time highs of 4.8 of 15 last season. Shooting percentages have hovered between the low of 30.8 in 1995-96 to the all-time high of 34.1 in 1988-89 (though the average attempts were just 5.5 that year).

The three-pointer not only changed the way the game was scored, but also the game’s tactics and strategies.

“Help-side defense was the staple of what everyone played before the three-point shot,” said West Virginia University men’s coach John Beilein. “You pressured the ball and there were always four guys waiting to help. With the three-point shot, if someone is waiting to help you can drive and kick the ball out to a shooter. Now, you are giving up three points.”

Officials also had to adjust their mechanics.

“You have to watch the feet, the contact and then any fouls after the shot,” said Marcy Weston, former NCAA women’s basketball rules secretary and officiating coordinator. “You have to get your sequence down about what you are looking for. People coming in the game now start with that, but before you didn’t have to watch where people’s feet were.”

Like most new rules, the three-pointer required an adjustment period. Many coaches had designated players who had the green light to shoot behind the arc.

Like most new rules, the three-pointer required an adjustment period. Many coaches had designated players who had the green light to shoot behind the arc.The first Division I men’s championship game under the new rule is a good example. Indiana University, Bloomington, defeated Syracuse University, 74-73, and the Hoosiers attempted just 11 three-pointers. But all-American guard Steve Alford was the designated shooter, hitting 7-of-10. Syracuse took only 10 three-point shots, all from guards Sherman Douglas and Greg Monroe.

Compare that to the 2005 title game between the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the University of Illinois, Champaign. North Carolina prevailed, 75-70, relying on the inside play of Sean May and an efficient 9-of-16 from three-point range. Illinois was the more perimeter-oriented team, finishing the game 12-of-40 from beyond the arc.

The three-point shot has become less of a specialty over time. Beilein, who has coached at West Virginia since 2002, is known for having multiple three-point threats on the court at all times.

“My teams have always recruited shooters even before the three-point line,” Beilein said. “After the rule change, it made it even more important to recruit shooters. I don’t think shooting was something people recruited as much. People were looking for more athleticism, quickness and defense then.”

He coached at Division II Le Moyne College when he inherited Len Rauch, an inside player with the versatility to make the three-point shot. When he took the head coaching job at Canisius University in 1992, he inherited another good shooting post player in Michael Meeks.

Then when he went to West Virgina, 6-11 center Kevin Pittsnogle was already on campus. His skills fit right in with Beilein’s system. Pittsnogle made 253 career three-pointers while shooting 41 percent.

“We ran a flex or a box-type of offense until the rule change,” Beilein said. “Then we started to spread the floor. If a kid can really shoot, he is a higher level of recruit for us. If he has the ability to make shots from the perimeter and is a big kid, the better it is for us.”

Effect on women’s game

The national trends on frequency and average number of three-pointers made at the Division I level have increased gradually through the years. Only once, in 2003-04, has the average number made been lower than the previous year.

“It was really accepted whole-heartedly, because the men had already done it,” said Weston, the senior woman administrator at Central Michigan University. “The dunk isn’t as prevalent in the women’s game, so the three-point shot added an element of excitement.”

The women’s game adopted the shot clock before the men to increase the pace of the game, and the three-pointer has continued to expand scoring.

“It opened up the game, because it allowed the post players to have a little more working room down on the box,” Lieberman said. “We can see their skills, and it makes teams make choices about whether they should double team.”

Bill Fennelly, the head women’s basketball coach at Iowa State University, heard from critics when the three-point rule entered the game.

“A lot of people thought it was a fluke or a trick shot,” Fennelly said. “The traditionalists out there couldn’t figure out why we were awarding more points for a basket because it was from farther away. For something that changed the game as dramatically as it did, there were a lot of people at the time who felt it wasn’t necessary.”

Fennelly was coaching at the University of Toledo and immediately embraced the new rule. He estimates his team attempted 30 three-point shots in the first game with the new rule.

Since he’s been at Iowa State, the three-point shot has become a significant marketing tool for his program.

“You have the loud public address announcement when someone makes one,” Fennelly said. “T-shirts get thrown to the crowd. It has dramatically changed the game. Our game is built on finesse, skill, passing and shooting. Maybe it is not as rugged and as athletic as the men’s game. But it allows someone with the skill set to shoot the ball and be a great part of what the game is about.”

While the line hasn’t moved in 20 years, some people favor a longer shot. The international distance, for example, is 20 feet, 6 inches. The NCAA has experimented with that arc but has not garnered enough momentum for a permanent change. The closest consideration came two years ago when a proposal packaged the longer three-pointer with a wider free-throw lane. Rules committees at that time agreed to leave the court markings alone until at least the 2007-08 season.

“I’m not a proponent of moving the line back, only because I don’t think anything is broken,” Beilein said. “The three-pointer and the shot clock have been ingenious as far as adding excitement to college basketball.”

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy