NCAA News Archive - 2007

« back to 2007 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Giant shoulders

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar puts into words what Harlem Renaissance put into him

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar puts into words what Harlem Renaissance put into him

|

By Greg Johnson

The NCAA News

The NCAA News

If he hadn’t become one of the all-time greats in basketball, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar would most likely be a history teacher.

But, as we know, his basketball skills led him to a different classroom, one that made him a defining character in the college and professional basketball landscape.

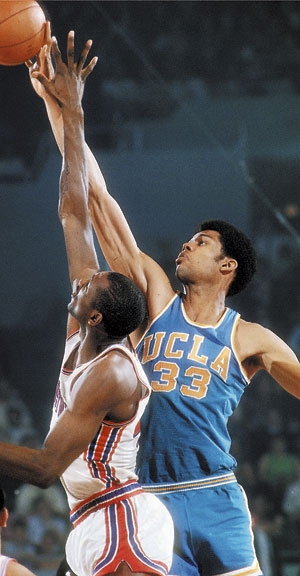

Still, even after a career that included three consecutive NCAA championships at the University of California, Los Angeles; six NBA titles; an NBA-record six MVP awards and being the league’s all-time leading scorer with 38,387 points, Abdul-Jabbar never lost his passion for the past.

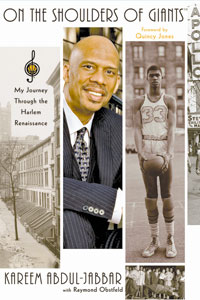

He has chronicled his zeal for history in a book called, “On the Shoulders of Giants: My Personal Journey through the Harlem Renaissance.”

Abdul-Jabbar, who was named one of the 100 Most Influential Student-Athletes in conjunction with the NCAA Centennial celebration in 2006, wrote the book to show how cultural changes in the African-American community between 1920 and 1940 helped shape his life — and American history.

The book covers Abdul-Jabbar’s four greatest passions: Harlem (where he was born in 1947), basketball, jazz and writing.

The book covers Abdul-Jabbar’s four greatest passions: Harlem (where he was born in 1947), basketball, jazz and writing.

In the summer between his junior and senior years of high school in 1964, Abdul-Jabbar joined the Harlem Youth Action Project, a government-sponsored anti-poverty program designed to keep children out of trouble and teach them about their heritage.

Until that point, Abdul-Jabbar didn’t realize how far removed from his culture he had become. Upon joining the group, though, he learned about the people whose writing, music and athletics accomplishments shaped African-American culture.

By sharing his knowledge on the subject today, Abdul-Jabbar hopes to remind people of past sacrifices that paved a better future.

“It is my attempt to wake up this generation caught up in the philosophy of ‘get rich or die trying,’ ” Abdul-Jabbar said. “They need to have a more fitting outlet for their aspirations and energy. The events and the personalities of the Harlem Renaissance serve as great examples of what to do and how to do it. This is my humble attempt at reviving that history.”

Going north

A number of the two million African-Americans who migrated to Northern cities from the South to escape lynching and Jim Crow laws found their way to Harlem. From 1910 to 1930 in fact, New York City’s African-American population grew from about 90,000 to 328,000.

African-American artists, musicians, writers, actors and athletes created a culture that had an impact both domestically and internationally. Harlem was considered the center of the universe for the African-American community.

Abdul-Jabbar, now 59, was influenced by the renaissance period after growing up in Manhattan. He writes how the New York Renaissance Big Five, winners of the first professional world basketball championship in 1939, helped show what kind of athlete he could become.

Just as importantly, he took in the music of Duke Ellington and Bessie Smith and became attracted to the writings of Langston Hughes, W.E.B. DuBois and Zora Neal Hurston.

Combine his love of history with being a teenager during the height of the Civil Rights movement, and it’s no wonder that Abdul-Jabbar wanted to improve the lives of those in the African-American community.

In 1964, Abdul-Jabbar, who was then known as Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr., enrolled in a journalism workshop and interacted with Martin Luther King Jr. when the civil-rights pioneer addressed the Harlem Youth Action Project.

“What I learned turned me on to the whole subject of Black history, and the need to communicate certain things that should be taught across generations,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “I felt very fortunate to have learned what I’ve learned when I learned it.”

About that time, Abdul-Jabbar became aware of the New York Renaissance Big Five basketball team. The all African-American squad was known simply as “the Rens” in Harlem. They barnstormed the country in the 1920s and 1930s, enduring racism both on and off the floor.

“They weren’t flying around in charter jets like today’s players,” Abdul-Jabbar said.

In March 1939, the Chicago Journal hosted the first world professional basketball championship, which was unique because it wasn’t segregated. That season, the Rens posted a record of 109-7, and they were placed in the same side of the 12-team bracket with the rival Harlem Globetrotters.

The two teams met in the semifinals, with the Rens winning, 27-23. Then they overcame a partisan crowd in the final to defeat the Oshkosh All-Stars, 34-25, to collect the $1,000 first prize.

“I would like for people who read the book to find out what it is like to be a professional basketball player back in the 1920s and 1930s during the Depression,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “It was a totally different landscape.”

Home influence

Abdul-Jabbar is quick to credit his parents, Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Sr. and Cora, for developing his love of music and writing. Alcindor Sr. was an avid reader and a graduate of the Julliard School of Performing Arts.

Alcindor Sr. also played trombone in several bands, and he and Cora sang for a chorus.

College was a subject that came up early and often in their household.

“We need to help parents get that message across to their kids,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “It is so important, and it really starts at home. We identified college as a goal when I was in the sixth or seventh grade. That’s when I started thinking about it.”

That was before it became apparent that he would become a legendary basketball player.

Before fourth grade, his parents sent him to a boarding school near Philadelphia. Though the school included eighth-graders, the 9-year-old Abdul-Jabbar was still the second tallest student.

His height, combined with his intelligence, made him a target of bullies. To escape their beatings, Abdul-Jabbar found solace on the basketball court, which led to his patented move — the sky hook.

One day he found himself surrounded along the baseline and couldn’t find anyone to pass to, so he pivoted and took a hook shot. Over the next three years, he worked on the shot along with some drills made famous by George Mikan, a basketball hall-of-famer who starred for the Minneapolis Lakers in the 1940s and 1950s. By the time he was in eighth grade, Abdul-Jabbar was proficient with the sky hook.

Abdul-Jabbar, currently a special assistant with the Los Angeles Lakers working primarily with teen-aged center Andrew Bynum, said he received better advice on how to play the game than today’s kids do.

“I don’t think the game is being coached very well at the grade school level these days,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “The (sky hook) is very effective and is a shot anyone can master if they apply themselves.”

He looks back on his days at UCLA, where he played under the legendary John Wooden, as an invaluable experience in his life. At the professional level, Abdul-Jabbar agrees with the NBA’s position of prohibiting players from entering the league until a year after high school graduation.

He also agrees with the current NCAA academic-reform movement, because it stresses the student part of student-athlete.

“I don’t know if we are going to see another world-class basketball player who also is a Rhodes Scholar, like Bill Bradley,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “Our nation is losing something in that regard. I hope we get a chance to change it.”

But, as we know, his basketball skills led him to a different classroom, one that made him a defining character in the college and professional basketball landscape.

Still, even after a career that included three consecutive NCAA championships at the University of California, Los Angeles; six NBA titles; an NBA-record six MVP awards and being the league’s all-time leading scorer with 38,387 points, Abdul-Jabbar never lost his passion for the past.

He has chronicled his zeal for history in a book called, “On the Shoulders of Giants: My Personal Journey through the Harlem Renaissance.”

Abdul-Jabbar, who was named one of the 100 Most Influential Student-Athletes in conjunction with the NCAA Centennial celebration in 2006, wrote the book to show how cultural changes in the African-American community between 1920 and 1940 helped shape his life — and American history.

The book covers Abdul-Jabbar’s four greatest passions: Harlem (where he was born in 1947), basketball, jazz and writing.

The book covers Abdul-Jabbar’s four greatest passions: Harlem (where he was born in 1947), basketball, jazz and writing.In the summer between his junior and senior years of high school in 1964, Abdul-Jabbar joined the Harlem Youth Action Project, a government-sponsored anti-poverty program designed to keep children out of trouble and teach them about their heritage.

Until that point, Abdul-Jabbar didn’t realize how far removed from his culture he had become. Upon joining the group, though, he learned about the people whose writing, music and athletics accomplishments shaped African-American culture.

By sharing his knowledge on the subject today, Abdul-Jabbar hopes to remind people of past sacrifices that paved a better future.

“It is my attempt to wake up this generation caught up in the philosophy of ‘get rich or die trying,’ ” Abdul-Jabbar said. “They need to have a more fitting outlet for their aspirations and energy. The events and the personalities of the Harlem Renaissance serve as great examples of what to do and how to do it. This is my humble attempt at reviving that history.”

Going north

A number of the two million African-Americans who migrated to Northern cities from the South to escape lynching and Jim Crow laws found their way to Harlem. From 1910 to 1930 in fact, New York City’s African-American population grew from about 90,000 to 328,000.

African-American artists, musicians, writers, actors and athletes created a culture that had an impact both domestically and internationally. Harlem was considered the center of the universe for the African-American community.

Abdul-Jabbar, now 59, was influenced by the renaissance period after growing up in Manhattan. He writes how the New York Renaissance Big Five, winners of the first professional world basketball championship in 1939, helped show what kind of athlete he could become.

Just as importantly, he took in the music of Duke Ellington and Bessie Smith and became attracted to the writings of Langston Hughes, W.E.B. DuBois and Zora Neal Hurston.

Combine his love of history with being a teenager during the height of the Civil Rights movement, and it’s no wonder that Abdul-Jabbar wanted to improve the lives of those in the African-American community.

In 1964, Abdul-Jabbar, who was then known as Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr., enrolled in a journalism workshop and interacted with Martin Luther King Jr. when the civil-rights pioneer addressed the Harlem Youth Action Project.

“What I learned turned me on to the whole subject of Black history, and the need to communicate certain things that should be taught across generations,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “I felt very fortunate to have learned what I’ve learned when I learned it.”

About that time, Abdul-Jabbar became aware of the New York Renaissance Big Five basketball team. The all African-American squad was known simply as “the Rens” in Harlem. They barnstormed the country in the 1920s and 1930s, enduring racism both on and off the floor.

“They weren’t flying around in charter jets like today’s players,” Abdul-Jabbar said.

In March 1939, the Chicago Journal hosted the first world professional basketball championship, which was unique because it wasn’t segregated. That season, the Rens posted a record of 109-7, and they were placed in the same side of the 12-team bracket with the rival Harlem Globetrotters.

The two teams met in the semifinals, with the Rens winning, 27-23. Then they overcame a partisan crowd in the final to defeat the Oshkosh All-Stars, 34-25, to collect the $1,000 first prize.

“I would like for people who read the book to find out what it is like to be a professional basketball player back in the 1920s and 1930s during the Depression,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “It was a totally different landscape.”

Home influence

Abdul-Jabbar is quick to credit his parents, Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Sr. and Cora, for developing his love of music and writing. Alcindor Sr. was an avid reader and a graduate of the Julliard School of Performing Arts.

Alcindor Sr. also played trombone in several bands, and he and Cora sang for a chorus.

College was a subject that came up early and often in their household.

“We need to help parents get that message across to their kids,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “It is so important, and it really starts at home. We identified college as a goal when I was in the sixth or seventh grade. That’s when I started thinking about it.”

That was before it became apparent that he would become a legendary basketball player.

Before fourth grade, his parents sent him to a boarding school near Philadelphia. Though the school included eighth-graders, the 9-year-old Abdul-Jabbar was still the second tallest student.

His height, combined with his intelligence, made him a target of bullies. To escape their beatings, Abdul-Jabbar found solace on the basketball court, which led to his patented move — the sky hook.

One day he found himself surrounded along the baseline and couldn’t find anyone to pass to, so he pivoted and took a hook shot. Over the next three years, he worked on the shot along with some drills made famous by George Mikan, a basketball hall-of-famer who starred for the Minneapolis Lakers in the 1940s and 1950s. By the time he was in eighth grade, Abdul-Jabbar was proficient with the sky hook.

Abdul-Jabbar, currently a special assistant with the Los Angeles Lakers working primarily with teen-aged center Andrew Bynum, said he received better advice on how to play the game than today’s kids do.

“I don’t think the game is being coached very well at the grade school level these days,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “The (sky hook) is very effective and is a shot anyone can master if they apply themselves.”

He looks back on his days at UCLA, where he played under the legendary John Wooden, as an invaluable experience in his life. At the professional level, Abdul-Jabbar agrees with the NBA’s position of prohibiting players from entering the league until a year after high school graduation.

He also agrees with the current NCAA academic-reform movement, because it stresses the student part of student-athlete.

“I don’t know if we are going to see another world-class basketball player who also is a Rhodes Scholar, like Bill Bradley,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “Our nation is losing something in that regard. I hope we get a chance to change it.”

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy