NCAA News Archive - 2006

« back to 2006 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

With scholarship increases unlikely, working group considers restructuring current practices

|

The NCAA News

The NCAA panel charged with addressing Division I baseball’s academic performance will concentrate on transfer issues at its next meeting October 22-23 in Indianapolis.

The 26-member Baseball Academic En-hancement Working Group will continue its discussions about the classroom performance of baseball student-athletes fresh off recent data indicating that baseball ranks second to last in graduation rates among all sports.

As the coaches and administrators do their best to figure out how to boost the academic results of baseball student-athletes, they have found themselves concentrating on the importance of retention. With Major League Baseball drafting about 1,500 players each June and transfer rules that don’t discourage players from hopping from one school to another, coaches don’t know what the makeup of their roster will be from one season to the next.

"The biggest impact we have on the Academic Progress Rate is the huge number of transfers we have in Division I," said working group member Dave Keilitz, the executive director of the American Baseball Coaches Association. "It’s very easy and liberal to transfer without penalty."

Baseball is one of the many NCAA sports for which student-athletes may use the one-time transfer exception to be immediately eligible at their new institution. Only basketball, football and men’s ice hockey do not employ the one-time transfer exception. The Division I governance structure defeated a legislative proposal to eliminate the exception for baseball last spring.

Keilitz said about 250 to 300 baseball student-athletes transfer every year, by far the highest figure for any Division I sport. He said that can be attributed in part to relaxed transfer rules, but also to the fact that baseball is an equivalency sport, which makes it easier for movement.

"Certainly, the low amount of financial aid that is given to student-athletes in baseball also reflects the number of transfers we have taking place," Keilitz said. "When a kid is only getting books for his aid package, it makes it a lot easier to go elsewhere."

Keilitz doesn’t believe that financial aid is directly tied to the academic performance of baseball student-athletes, but is convinced that it is a factor in the high transfer rates.

"I don’t think you can tie financial aid into performance academically. Whether a kid is getting good grades or bad grades doesn’t have anything to do with how much aid he’s getting," Keilitz said.

Wake Forest Athletics Director Ron Wellman, who chairs the working group, also recognizes that the high transfer rate among baseball student-athletes is due at least in part to the current structure of financial aid.

"When you look at baseball and the number of players on a team and the amount of aid available, it’s the least-funded sport," Wellman said. "How we structure financial aid is a point of discussion. One of the reasons we feel there is a high transfer rate is because of the financial aid that is currently available to players."

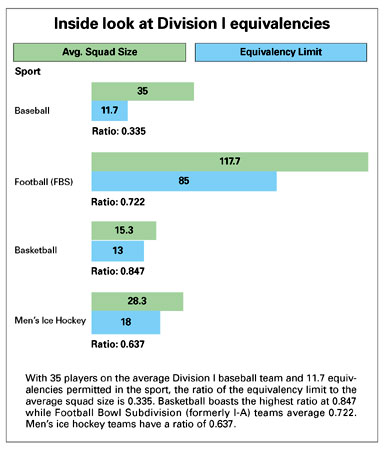

In fact, with 9,996 baseball student-athletes competing on 286 teams at the Division I level, the average squad has 35 players on its roster.

With 11.7 scholarships spread among those student-athletes, the ratio of equivalency limit to average squad size in baseball is 0.335. When compared with football, basketball and men’s ice hockey, baseball is significantly less funded.

The amateur draft also has a significant impact on the retention of baseball student-athletes. Wellman said that the Academic Progress Rate can be adversely affected because of baseball players who bolt for the professional game and don’t finish their schoolwork.

"You lose the retention point if you lose players to the professional draft," Wellman said. "We know that there are certain players who have their minds made up very early in the last semester of their collegiate career that they are going to turn professional and sign. That impacts the retention of the student-athlete and has a harmful effect on a team’s APR."

With about 5 percent of baseball student-athletes moving on to sign professional contracts each year, the working group is cognizant that restructuring financial aid may provide some with an incentive to finish their degrees.

"Whether it’s right or wrong in their thinking, most Division I baseball players have expectations of being professional baseball players down the road. If they come in for just books and aren’t playing, they’re gone," Keilitz said. "If you come in for tuition and fees, which is a more substantial amount, you might stick around longer."

But the NCAA working group isn’t looking for more financial aid. Indeed, when the Division I Board of Directors appointed the group last spring, the presidents asked for academic improvement without relying on more scholarships, which they thought was an impractical — and unaffordable — solution for most schools.

Given those parameters, the working group is looking at different financial aid models that might reduce transfer rates. Keilitz suggests taking the dollars needed to dole out the permitted 11.7 scholarships and dividing them among a standard number of awards. If everyone receives the same amount, Keilitz says, there won’t be so much jumping around.

To be sure, coaches have been frustrated with the way financial aid is structured in baseball. Louisiana State University coach Paul Mainieri believes that baseball programs could use more scholarships.

"As a coach, you have to ask yourself what you need to have and where you need to spend the majority of your scholarship money to be competitive on a consistent basis," said Mainieri, who also is a member of the working group. "We can absolutely use more scholarships. The quality of the game would improve dramatically because we could favorably compete with professional baseball for student-athletes to come to college."

Mainieri said high school players are more likely to sign contracts if they don’t receive appropriate scholarship offers. Too often, he says, it comes down to a financial decision that 17- and 18-year-olds shouldn’t have to make.

"I think we’re losing a lot of kids who could get an education and contribute to a college baseball program simply because of financial situations. It’s been a trend for many years now," Mainieri said.

Keilitz, though, realizes that the working group may not have many sweeping options when it comes to changing the financial aid paradigm.

"The biggest reason baseball teams are struggling is because of the transfer factor. But tied to the transfer factor is the lack of funds available for scholarships," Keilitz said. "I hope we can come up with a model that may enhance our overall grant-in-aid structure."

Mainieri believes that college baseball’s financial issues also are keeping prospective minority student-athletes away from the diamond.

"If you’re a young kid, and maybe you come from a situation where your family doesn’t have a lot of money, and you have an opportunity to earn a college scholarship, are you going to play a sport where you can earn a full scholarship, or a sport where you’re lucky if you can earn half of a scholarship and have to pay the rest?" Mainieri asked. "I think we’ve lost a lot of the minority kids. They haven’t had an opportunity to come to college because we’re breaking the scholarships into such small increments that a lot of families can’t afford it. They’re getting involved in football and basketball instead."

Increased scholarship opportunities, Mainieri says, are one way to help baseball solve its academic issues.

"When a kid isn’t pleased with his playing time and he has to pay significant money to go to that school and sit on the bench, the financial aspect does play into it," Mainieri said.

At its meeting this month, the working group will discuss financial aid issues as they relate to retention and the academic performance of baseball’s student-athletes.

The group hopes to make recommendations to the Division I Board of Directors before its April meeting.

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy