NCAA News Archive - 2006

« back to 2006 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

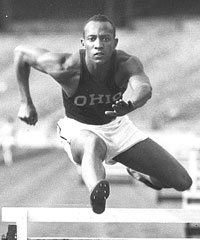

Jesse Owens never stopped inspiring others after running and jumping his way into history

|

The NCAA News

Jesse Owens lives on in history as arguably the greatest American track athlete ever, rightly remembered and revered for great and inspirational deeds — primarily for claiming four gold medals at the 1936 Olympic Games in Nazi Germany.

His name also remains firmly etched in collegiate records books as the only individual to win four track events during a single NCAA championships meet — a feat he accomplished twice.

Today, however, Owens looms so large in legend that it’s a challenge — even a bit uncomfortable — to peer back into time and see him as he was in May 1935.

When that month dawned, he was a 21-year-old sophomore at Ohio State University, struggling with classes as a physical education major as he devoted countless hours to training and then to supporting a family, including an infant daughter. And, the times being what they were, he also endured segregated housing, while regularly suffering the indignity of being denied service at diners on road trips, or a room with teammates in a hotel.

However, one day that month, his life — if not all of his circumstances — changed dramatically.

It happened

As he cleared the last barrier shortly after

It’s now considered one of the 25 Defining Moments of the NCAA, but it also possibly was the defining moment of Jesse Owens’ life.

Owens is remembered for his accomplishments 15 months later in

“Your August 2nd ...with many of you, it is coming,” he said.

But his life utterly changed that May day on the Ferry Field track at the

‘The greatest performance’

Owens wasn’t unknown when he arrived in

However, he moved through life generally unrecognized except by friends or competitors, until that May afternoon before 12,000 fans — mostly

He gingerly shook off a back injury sustained a few days earlier while he was “horsing around” with friends, and promptly equaled — for the second time in two weeks — the world mark in the 100-yard dash. The crowd stirred.

Accounts differ on how long the entire sequence of events took, but it may have been as few as 45 minutes and almost surely no more than 70. Feeling physically fine after testing his sore back in the 100, Owens moved to the long jump, which already was in progress and where his chief competitor already had posted two leaps.

In one attempt, Owens sailed beyond 26 feet, shattering the world record by half a foot.

It probably was only 20 to 25 minutes later when Owens crossed the finish line in the 220-yard final with a time of 20.3 seconds — three-tenths of a second better than the world standard.

Then it was on to the hurdles, and that first stride into immortality. He finished in 22.6 seconds — again, three-tenths of a second better than the world mark.

“Considering the equipment he used and the surface he ran on, I think it was the greatest performance any athlete will ever do in any sport,” 95-year-old Kenneth “Red” Simmons recalled 70 years later in a 2005 Columbus Dispatch article by columnist Todd Jones. Simmons, himself a 1932 Olympian and the founding coach of

Another observer — a student at

“I saw Jesse Owens at a Big Ten track meet in Ann Arbor, as one of some 10,000 or 12,000 spectators, when he broke three world records and tied a fourth,” said President Gerald Ford during his presentation of the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Owens at a White House ceremony. “His performance that day in the (long) jump — 26 feet, 8 1/4 inches — was not equaled for 25 years. It was a triumph that all of us will remember.”

A ‘special case’

Starting that day in

One article inaccurately reported his engagement to the daughter of a well-to-do

He returned to

Owens, now a junior, ran in an

He apparently expected to come back to

As he pondered his future and grew weary from racing and homesick for

After supporting his family through a series of jobs and racing exhibitions — on occasion running against a horse — he attempted to return to school in the early 1940s, but again struggled academically.

In addition to attending class, he ran a dry-cleaning business to support what was now a family of five, while also assisting with the

“In December 1940, his poor exam results could have resulted in expulsion, yet OSU acknowledged that his personal circumstances made him a ‘special case’,” McRae wrote in a 2002 dual biography of Owens and boxer Joe Louis. “He battled on. A year later, his marks were no better. Jesse had no choice. He dropped out again.”

Inspiration and motivation

Ultimately, a few years later, Owens found his true calling — working with children. He also did public relations work, which generally consisted of endorsing products, to pay the bills. However, he channeled his passion into motivating youngsters to achieve a better life, not only around

“He was a firm believer in the youth of any country being its future,” his youngest daughter, Marlene Owens Rankin, said in a recent interview with Michelle Brutlag Hosick of The NCAA News. “In that regard, he wanted to help them be the best that they could be by realizing their full potential. He didn’t forget the help that he received as a young man from (Charles Riley) and the lessons learned from him. He attributed those ‘gifts’ as the key to his future success.”

When President Ford presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Owens, the honor recognized that belief as much as it reflected his athletics achievement.

“He brought his own talents into the service of others,” Ford said. “As a speaker, as an author, as a coach, he has inspired many young men and women to achieve their very best for themselves and for

After Owens’ death in 1980, Marlene Owens and other family members began receiving money unsolicited from Americans who had been touched both by her father’s accomplishments and beliefs.

Those funds were used to start the Jesse Owens Foundation, which now annually awards dozens of college scholarships — including funding for students in The Ruth and Jesse Owens Scholars Program at

‘Great all his life’

Today, it’s tempting to wonder how differently things may have turned out for Owens had current restrictions on hours of practice and dates of competition been in place in 1935; or had academic support been available to a struggling collegiate athlete; or had a degree-completion scholarship been available to a man who was motivated enough to return to school despite family demands.

However, the fact is that Owens achieved greatness both in and beyond sports — and became the legend he remains today — without those aids, and despite the difficult circumstances of his collegiate days.

When Owens received the NCAA’s Teddy Award in 1974, he brought along his collegiate coach, Larry Snyder, as his honored guest. Recalling that “attending Ohio State University at that time was somewhat of a difficult problem from the standpoint of being able to share as all Americans could share” — Owens’ soft-spoken way of remembering the bigotry and discrimination he endured as a collegiate athlete — he noted that Snyder “made me feel that I was part of that organization, part of that team.”

Six years later, upon Owens’ death, Snyder returned the compliment in an interview with Bob Hunter of the Columbus Dispatch.

“He was a great track star then, and he was great all his life,” said Snyder, who was 83 years old then. “His attitudes and beliefs helped me and thousands of other people. He was a tremendous human being.”

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy