NCAA News Archive - 2006

« back to 2006 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

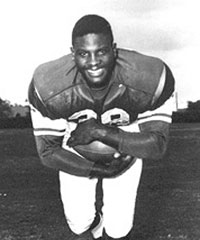

Oklahoman Gautt’s pioneering journey, unwavering advocacy blazed new trails

|

The NCAA News

In fall 1956, 18-year-old Prentice Gautt rode 20 miles in a car from his Oklahoma City home, then stepped out the door from an all-black to an all-white world.

Before graduating from Douglass High School, Gautt was president of the senior class and a member of the National Honor Society. But when he left that car at the front entrance of the University of Oklahoma, he became one of the then-recently desegregated institution’s first black undergraduate students — and he was destined to become the first Black to play football for the Sooners.

The teenager earned admission to his home-state university on his academic record, then used a sport he excelled in — he was, after all, the first black player selected for Oklahoma’s high school all-star game — to gain the means to attend.

But Gautt understood he also needed the support of others to accomplish that goal, and it was a lesson he took to heart.

Today, the most noteworthy thing to remember about Gautt — the achievement that makes his admission to Oklahoma one of the Top 25 Defining Moments of the NCAA — is that this man of many firsts paid his debt to those who supported him by becoming a tireless champion of thousands of student-athletes who followed in his footsteps.

When his playing days ended after an eight-year professional career, Gautt tried coaching but decided he could be more helpful in another way — as a counselor. He completed a doctorate in counseling psychology at the University of Missouri, Columbia — where a few years earlier he had joined Dan Devine’s staff as one of the first two black assistants in the Big Eight Conference — and then joined the Missouri education faculty, which put him in a position to coordinate campus counseling programs.

He focused on minority students and athletes.

"I saw myself in a lot of them," he recalled years later in an interview with his friend Carol Burr, the longtime editor of Sooner Magazine, a quarterly publication of the University of Oklahoma Foundation.

"I knew the importance of having somebody to talk to, somebody to say, ‘Yeah, I care.’ "

In many ways, Gautt arrived alone in Norman. He roomed alone in the athletics dormitory during his freshman year, took care not to be seen talking to white female classmates on campus, and only occasionally traveled the 20 miles back to Oklahoma City to socialize with neighbors and friends.

But he also arrived with the backing of his community. A group of black doctors and pharmacists in Oklahoma City created a four-year "scholar-athlete" scholarship to pay Gautt’s way to the university. They chose the youngster because they believed he could succeed in a hostile environment.

And Gautt also had the backing of the most respected man in Oklahoma — Sooners football coach Bud Wilkinson.

"He could say to me, ‘You can be a part of my program. Regardless of what other people think or feel or do, I want to you be a part of my program,’ " Gautt told Burr in remembering Wilkinson.

Within a couple of months of Gautt’s arrival on campus, Wilkinson returned the private money funding the young man’s education and quietly awarded Gautt an athletics scholarship.

Along the way, others stepped up on Gautt’s behalf. Teammate Jakie Sandefer, who was competing with Gautt to start at halfback for the Sooners, insisted that the team honor its tradition of putting position players together in the same room during road trips — even as Wilkinson’s bigger concern was finding hotels that would permit Gautt to take a room at all.

The two roomed together for a couple of years, and years later, Sandefer spoke again for Gautt when his teammate was inducted into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame.

"Yeah, Prentice was different," Sandefer recalled. "He had more class than the rest of us, and he was a better student."

He also continued racking up achievements both on and off the field — ranging from throwing the block that allowed quarterback David Baker to score the Sooners’ first two-point conversion under a recent rule change, to becoming the first black player to score in the Orange Bowl, on a 42-yard run on the second play of the 1959 game.

Notably, Gautt also earned Academic All-America honors during his senior season.

Gautt continued to play the sport with the St. Louis Browns and then the Cardinals, but like the car that transported him to the front door of his alma mater, football proved to be merely the ride that carried him to his real life’s calling.

In 1979, four years after joining the Missouri education faculty, he was offered a job as assistant commissioner of the Big Eight. He expected he would work in the league’s Kansas City office for a short while to gain some experience in athletics administration, then return to campus.

Instead, he maintained his association with the league for the rest of his life — long after its transition into today’s Big 12. He eventually served as the conference’s associate commissioner in charge of eligibility, enforcement and education. He soon became an influential voice within the NCAA, as well.

Gautt was a staunch supporter of the tougher academic standards that Division I enacted during the 1980s. A few years later, during his term as the NCAA’s secretary-treasurer, he helped defend the adoption of Proposal No. 16 as a participant in federally sponsored mediation between the NCAA and the Black Coaches Association. What prompted the review were allegations that data supporting the legislation had been tainted by researchers’ professional involvement with an academician who appeared to believe in racial supremacy.

Gautt, however, did not support the standards blindly. He endorsed core-curriculum requirements without hesitation, but worried about whether standardized tests unfairly affected black students. Ultimately, using data produced by the same researchers Gautt had helped defend during the federal mediation, the Association in 2003 stopped using test scores as a cutoff for determining athletics eligibility.

In the Big Eight and then the Big 12, Gautt left his mark as an advocate of life-skills programs and as a mentor to the conference student-athlete advisory committee. The work reflected the long-held philosophy he expressed during his 1987 interview with Sooner Magazine’s Burr, when she asked, how can a highly recruited student-athlete keep his head on straight?

"Some of them don’t," he replied. "And then they get to the institution and find kids there who are just as good as they are if not better. Then there has to be somebody around to help pick up the pieces. Otherwise the kid may finally decide, ‘I’m not as good as I thought I was,’ and somehow just give up — and that’s really sad."

In May 2004, the Big 12 named its postgraduate scholarship program in Gautt’s honor, thus ensuring that dozens of student-athletes who receive the awards in coming years not only will receive support for their educational dreams, but benefit from the example that Gautt provided in his own pursuit of a calling beyond athletics.

"Academics have been a major part of my life for as long as I can remember," Gautt said when the honor was announced. "To have this honor is a great way to be acknowledged. This is an overwhelming recognition by this conference. I’m appreciative, very appreciative."

Sadly, only 10 months later, Gautt suddenly fell ill with flu-like symptoms, then died a few days later at age 67.

His death came as a shock to friends, colleagues and, most of all, those he mentored through the years.

One who benefited from Gautt’s care — Derrick Gragg, an athletics administrator at another Southern school, the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville — wrote in The NCAA News of crying when he heard the news, then described Gautt’s impact in Gragg’s chosen profession.

"Without Prentice Gautt and other outstanding pioneers," he said, "there would be no Gene Smith, Herman Frazier or Keith Tribble. There would be no Mike Garrett, Darryl Gross or Warde Manuel. There would also be no great memories of former college greats Archie Griffin, Charles Woodson, Cornelius Bennett, Charlie Ward, Bo Jackson or Barry Sanders."

At the end of his life, this man of many firsts ultimately had put student-athletes first — and by doing so helped change the face of the NCAA and of intercollegiate athletics.

In Oklahoma, where that young man destined to influence others found his own early mentors, the university already had paid its own lasting tribute.

In 1999, the university opened the Prentice Gautt Academic Center, located on two floors inside the stadium where Gautt smashed the color barrier in Sooner sports. It observed the occasion by asking Gautt to participate in a ceremony marking the center’s opening during halftime of a football game.

Sooner Magazine’s Burr described the moment in a published tribute to Gautt after his death, writing that the "standing ovation went on and on."

Nearly seven years later, she still marks that moment as one of her favorites in Sooner football history.

"The crowd went crazy cheering him, and I had to remember how long it had been since he had been at OU — he was ancient history to most of them," she said. "He was a special man."

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy