NCAA News Archive - 2006

« back to 2006 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Defining the future

Television agreements established support funds for student-athletes

Television agreements established support funds for student-athletes

|

By Jack Copeland

The NCAA News

The NCAA News

A series of agreements for televising the Division I Men’s Basketball Championship — leading to the current 11-year, $6 billion plan that broke new ground by bundling together television and marketing rights for all of the NCAA’s championships — provided the primary tools for defining the modern Association.

Like several other defining moments in the NCAA’s first century, the broadcast contracts ultimately will be more important for the changes they produce than for the mere fact they happened — eye-popping as the dollar amounts of those agreements may be.

After all, the first NCAA championship in 1921 is remembered today more as the starting place for today’s 88 championship events than for who scored the most points in that inaugural track and field meet.

Likewise, Walter Byers’ assignment in 1951 to open a national office is remembered for establishing a regulatory authority over intercollegiate athletics (through enforcement activities and renewed efforts toward academic reform), and for responding to a growing membership’s need for new services and resources. The office’s physical location and size of the staff are simply more data — interesting statistically but only of passing importance.

The achievements of Jesse Owens and James Frank, Pat Summitt and Judith Sweet, and the Loyola University (Illinois) men’s basketball team and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, women’s soccer team probably are more important as markers of the inclusion of minorities and women in NCAA competition and governance than as examples of personal triumph.

As statistics go, the money gained from agreements during the past two decades with CBS, ESPN and other business partners is remarkable. It’s impossible to overlook the fact that revenues from those contracts provide more than 85 percent of the Association’s half-billion dollars in annual operating revenue.

The Association’s history, however, suggests those agreements someday will be remembered less for how much money they earned, and more for how that money changed the NCAA.

Without a doubt, those dollars made the NCAA bigger by attracting new members, which in turn prompted the creation of better championships, new programs and broader membership services.

However, those agreements also produced something new, and therefore historically important: They provided funding for the first time for initiatives specifically designed to support the well-being of student-athletes, regardless of what sport they played or whether they qualified to compete in NCAA championships.

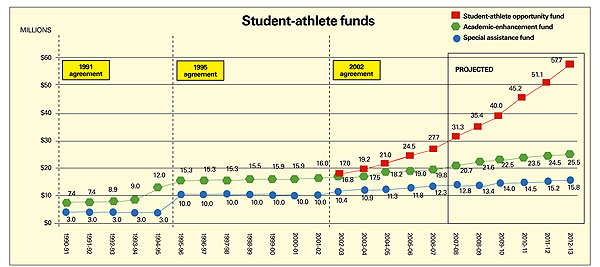

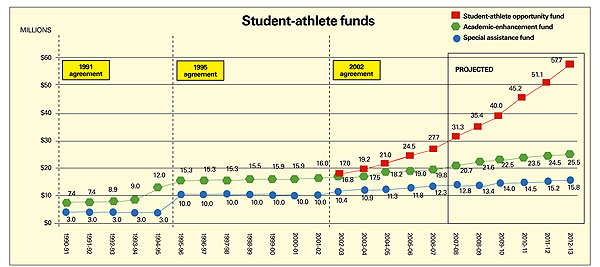

That support — which will exceed $80 million this year and continue to grow annually — comes from an array of programs whose genesis is directly traceable to a $1 billion agreement with CBS beginning in 1991, and whose impact was dramatically bolstered by the current agreements with CBS and ESPN beginning in 2002-03.

The verdict is still out on whether all that money will change the NCAA for the better, like other defining moments in the Association’s history. Perhaps the ultimate arbiters of that debate will be student-athletes themselves, as they demonstrate how their lives are being impacted by NCAA support for programs ranging from catastrophic-injury insurance to conference and institutional academic- and personal-support funds to an assortment of scholarship programs.

‘Bigger picture’

Whatever that verdict eventually may be, the effort’s importance already has been noted by former NCAA officer Joe Crowley in his recent history of the Association’s first century, “In the Arena.”

“All of these programs and activities are part of the substantial effort undertaken in recent years, both on campuses and in conference offices, as well as by the NCAA, to make student-athletes the Association’s highest priority,” he wrote. “It’s a story that needs telling. It’s the biggest part of the bigger picture.”

The historical record indicates that NCAA leaders immediately perceived that the broadcast agreements promised more for the Association than organizational enrichment. On the day in 1989 when then-NCAA Executive Director Richard Schultz announced the $1 billion agreement with CBS, he and other leaders challenged the membership to be creative in reaping the windfall.

“As your executive director, and along with the negotiating committee, we would challenge the membership to use these new funds to enhance the worthy goals of intercollegiate athletics within the framework of higher education, and not to increase the pressure placed on coaches and athletes,” he said.

The membership responded through a Special NCAA Advisory Committee to Review Recommendations Regarding Distribution of Revenues, which, as expected, urged in accordance with custom that the lion’s share of the proceeds be returned to institutions. This time, however, the committee added new criteria that acknowledged the number of sports sponsored and scholarships awarded by schools, in addition to success on the basketball court.

The committee’s recommendations also broke ground in another way, through three uses beginning in 1990-91 of funds explicitly to benefit student-athletes:

Expansion of the Catastrophic-Injury Insurance Program to benefit all student-athletes in all NCAA divisions — not just participants in Division I men’s and women’s basketball and NCAA championships, which had been made possible by earlier contracts with CBS.

Establishment of a Needy Student-Athlete Fund (later renamed the Special Assistance Fund), from which conferences could assist Pell Grant-eligible student-athletes with such emergencies as medical, travel and educational expenses and clothing needs.

Creation of an Academic Enhancement Fund, under which each institution then received $25,000 annually (and today receives more than $58,000 annually) to support academic programs for student-athletes.

During 1990-91, the first year of that broadcast agreement, the NCAA allocated $15.25 million to those programs, in addition to funding scholarship programs supporting completion of academic degrees by student-athletes whose eligibility to compete had expired, as well as for minorities and women seeking advanced degrees in athletics administration.

Other portions of the windfall also helped spur student-athlete involvement in the actual governance of the Association, as the creation of the three divisions’ Student-Athlete Advisory Committees (as well as private support for the CHAMPS/Life Skills Program administered jointly by the NCAA and the Division I-A Athletic Directors Association) led to the development of the NCAA Leadership Conference — an annual gathering of student-athletes for discussion of issues and enhancement of personal skills.

The federation of the Association in 1997 prompted Divisions II and III — armed with a constitutionally mandated share of NCAA television and other revenues — to emulate Division I’s support for student-athlete well-being in their own programming.

In addition to resulting in the creation of divisional student-athlete leadership conferences, those funds have supported programs ranging from conference grants to the Division II National Championships Festivals to the upcoming Division III pilot drug-education and testing program.

As revenues from television agreements grew though the years, so did NCAA support for student-athlete programs, until $45 million was allocated in 2001-02 to the three specific programs that had been inaugurated in 1990-91.

Boosting the commitment

The principle of supporting student-athlete well-being was well established by the time the $6 billion bundled-rights plan began in fall 2002.

But the breathtaking increase in revenue produced by that plan enabled a 45 percent increase in funding for student-athlete programs from the previous agreement.

Most of the increase was directly attributable to a new program, the Student-Athlete Opportunity Fund, approved by the Division I Board of Directors and authorized to distribute $17 million during its first year.

The program was notable because, for the first time, it provided direct benefits through conference offices to student-athletes without requiring that they demonstrate need as was required in the Special Assistance Fund.

“The significance of this fund is that it can be customized by each conference to meet the needs of the conference’s student-athletes,” Division I Management Council Chair Chris Plonsky said at the time. “It is structured in particular to try to get the appropriate dollars into the hands of student-athletes to help toward their educational goals.”

The amount available to student-athletes through the fund will increase annually by 13 percent through the remainder of the bundled-rights agreement, which expires in 2013. In 2005-06, more than 38,000 student-athletes received grants from that year’s $24 million fund. In 2012-13, more than $57 million will be allocated to that fund, in addition to more than $25 million to the academic enhancement fund and $15 million to the Special Assistance Fund.

By then, history likely will more fully reveal the verdict on whether the broadcast agreements supporting those plans are more noteworthy for the money they generated, or for how that money is defining the NCAA.

Former NCAA President Ced Dempsey may have established the parameters for making that judgment when he reacted to a journalist’s question in 2002 about whether the large contracts negotiated with CBS and ESPN “jibed” with recent criticism by the Knight Foundation on Intercollegiate Athletics — a panel on which Dempsey served as a member — of increasing commercialization of college sports.

“No one ever said money was bad,” Dempsey responded.

“It’s about how the money is used and how we help enhance opportunities for student-athletes, and making sure the money doesn’t corrupt what our mission is — and that’s the education of our student-athletes.”

Like several other defining moments in the NCAA’s first century, the broadcast contracts ultimately will be more important for the changes they produce than for the mere fact they happened — eye-popping as the dollar amounts of those agreements may be.

After all, the first NCAA championship in 1921 is remembered today more as the starting place for today’s 88 championship events than for who scored the most points in that inaugural track and field meet.

Likewise, Walter Byers’ assignment in 1951 to open a national office is remembered for establishing a regulatory authority over intercollegiate athletics (through enforcement activities and renewed efforts toward academic reform), and for responding to a growing membership’s need for new services and resources. The office’s physical location and size of the staff are simply more data — interesting statistically but only of passing importance.

The achievements of Jesse Owens and James Frank, Pat Summitt and Judith Sweet, and the Loyola University (Illinois) men’s basketball team and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, women’s soccer team probably are more important as markers of the inclusion of minorities and women in NCAA competition and governance than as examples of personal triumph.

As statistics go, the money gained from agreements during the past two decades with CBS, ESPN and other business partners is remarkable. It’s impossible to overlook the fact that revenues from those contracts provide more than 85 percent of the Association’s half-billion dollars in annual operating revenue.

The Association’s history, however, suggests those agreements someday will be remembered less for how much money they earned, and more for how that money changed the NCAA.

Without a doubt, those dollars made the NCAA bigger by attracting new members, which in turn prompted the creation of better championships, new programs and broader membership services.

However, those agreements also produced something new, and therefore historically important: They provided funding for the first time for initiatives specifically designed to support the well-being of student-athletes, regardless of what sport they played or whether they qualified to compete in NCAA championships.

That support — which will exceed $80 million this year and continue to grow annually — comes from an array of programs whose genesis is directly traceable to a $1 billion agreement with CBS beginning in 1991, and whose impact was dramatically bolstered by the current agreements with CBS and ESPN beginning in 2002-03.

The verdict is still out on whether all that money will change the NCAA for the better, like other defining moments in the Association’s history. Perhaps the ultimate arbiters of that debate will be student-athletes themselves, as they demonstrate how their lives are being impacted by NCAA support for programs ranging from catastrophic-injury insurance to conference and institutional academic- and personal-support funds to an assortment of scholarship programs.

‘Bigger picture’

Whatever that verdict eventually may be, the effort’s importance already has been noted by former NCAA officer Joe Crowley in his recent history of the Association’s first century, “In the Arena.”

“All of these programs and activities are part of the substantial effort undertaken in recent years, both on campuses and in conference offices, as well as by the NCAA, to make student-athletes the Association’s highest priority,” he wrote. “It’s a story that needs telling. It’s the biggest part of the bigger picture.”

The historical record indicates that NCAA leaders immediately perceived that the broadcast agreements promised more for the Association than organizational enrichment. On the day in 1989 when then-NCAA Executive Director Richard Schultz announced the $1 billion agreement with CBS, he and other leaders challenged the membership to be creative in reaping the windfall.

“As your executive director, and along with the negotiating committee, we would challenge the membership to use these new funds to enhance the worthy goals of intercollegiate athletics within the framework of higher education, and not to increase the pressure placed on coaches and athletes,” he said.

The membership responded through a Special NCAA Advisory Committee to Review Recommendations Regarding Distribution of Revenues, which, as expected, urged in accordance with custom that the lion’s share of the proceeds be returned to institutions. This time, however, the committee added new criteria that acknowledged the number of sports sponsored and scholarships awarded by schools, in addition to success on the basketball court.

The committee’s recommendations also broke ground in another way, through three uses beginning in 1990-91 of funds explicitly to benefit student-athletes:

Expansion of the Catastrophic-Injury Insurance Program to benefit all student-athletes in all NCAA divisions — not just participants in Division I men’s and women’s basketball and NCAA championships, which had been made possible by earlier contracts with CBS.

Establishment of a Needy Student-Athlete Fund (later renamed the Special Assistance Fund), from which conferences could assist Pell Grant-eligible student-athletes with such emergencies as medical, travel and educational expenses and clothing needs.

Creation of an Academic Enhancement Fund, under which each institution then received $25,000 annually (and today receives more than $58,000 annually) to support academic programs for student-athletes.

During 1990-91, the first year of that broadcast agreement, the NCAA allocated $15.25 million to those programs, in addition to funding scholarship programs supporting completion of academic degrees by student-athletes whose eligibility to compete had expired, as well as for minorities and women seeking advanced degrees in athletics administration.

Other portions of the windfall also helped spur student-athlete involvement in the actual governance of the Association, as the creation of the three divisions’ Student-Athlete Advisory Committees (as well as private support for the CHAMPS/Life Skills Program administered jointly by the NCAA and the Division I-A Athletic Directors Association) led to the development of the NCAA Leadership Conference — an annual gathering of student-athletes for discussion of issues and enhancement of personal skills.

The federation of the Association in 1997 prompted Divisions II and III — armed with a constitutionally mandated share of NCAA television and other revenues — to emulate Division I’s support for student-athlete well-being in their own programming.

In addition to resulting in the creation of divisional student-athlete leadership conferences, those funds have supported programs ranging from conference grants to the Division II National Championships Festivals to the upcoming Division III pilot drug-education and testing program.

As revenues from television agreements grew though the years, so did NCAA support for student-athlete programs, until $45 million was allocated in 2001-02 to the three specific programs that had been inaugurated in 1990-91.

Boosting the commitment

The principle of supporting student-athlete well-being was well established by the time the $6 billion bundled-rights plan began in fall 2002.

But the breathtaking increase in revenue produced by that plan enabled a 45 percent increase in funding for student-athlete programs from the previous agreement.

Most of the increase was directly attributable to a new program, the Student-Athlete Opportunity Fund, approved by the Division I Board of Directors and authorized to distribute $17 million during its first year.

The program was notable because, for the first time, it provided direct benefits through conference offices to student-athletes without requiring that they demonstrate need as was required in the Special Assistance Fund.

“The significance of this fund is that it can be customized by each conference to meet the needs of the conference’s student-athletes,” Division I Management Council Chair Chris Plonsky said at the time. “It is structured in particular to try to get the appropriate dollars into the hands of student-athletes to help toward their educational goals.”

The amount available to student-athletes through the fund will increase annually by 13 percent through the remainder of the bundled-rights agreement, which expires in 2013. In 2005-06, more than 38,000 student-athletes received grants from that year’s $24 million fund. In 2012-13, more than $57 million will be allocated to that fund, in addition to more than $25 million to the academic enhancement fund and $15 million to the Special Assistance Fund.

By then, history likely will more fully reveal the verdict on whether the broadcast agreements supporting those plans are more noteworthy for the money they generated, or for how that money is defining the NCAA.

Former NCAA President Ced Dempsey may have established the parameters for making that judgment when he reacted to a journalist’s question in 2002 about whether the large contracts negotiated with CBS and ESPN “jibed” with recent criticism by the Knight Foundation on Intercollegiate Athletics — a panel on which Dempsey served as a member — of increasing commercialization of college sports.

“No one ever said money was bad,” Dempsey responded.

“It’s about how the money is used and how we help enhance opportunities for student-athletes, and making sure the money doesn’t corrupt what our mission is — and that’s the education of our student-athletes.”

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy