NCAA News Archive - 2005

« back to 2005 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

|

The NCAA News

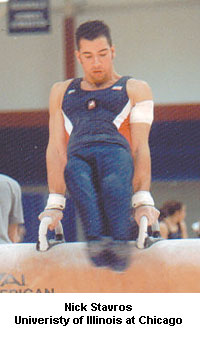

Nick Stavros, a gymnast at the University of Illinois at Chicago, aspires to become a lawyer.

If he applies the same determination to that dream that he has to overcoming a rare birth defect that leaves him without use of 66 percent of the muscles in his legs, there's no question he will make it to the courtroom.

Stavros was born with arthrogryposis, a rare birth defect that affects the soft tissue. The condition, which strikes just one in 10 million babies, is not progressive, and the majority of children with the defect are affected throughout their body. But in Stavros' case, only his legs and feet were impacted. He has no working calf muscles and hamstrings, one knee doesn't bend completely and he was born with feet so severely clubbed that he couldn't be stood up on his mother's lap.

"His feet faced up and his toes touched his heels, folded in half," said Roseanne Stavros, mother of the junior criminal justice major. At that time, doctors avoided operating on babies with club feet who were less than a year old because it was thought to be too risky. But the Stavros family persuaded doctors to do so on 4-month-old Nick because his case was so severe -- a decision that not only produced excellent results, but also changed the way medicine approached such cases.

"His feet faced up and his toes touched his heels, folded in half," said Roseanne Stavros, mother of the junior criminal justice major. At that time, doctors avoided operating on babies with club feet who were less than a year old because it was thought to be too risky. But the Stavros family persuaded doctors to do so on 4-month-old Nick because his case was so severe -- a decision that not only produced excellent results, but also changed the way medicine approached such cases.

At 14 months of age, Stavros underwent surgery to repair a dislocated hip, with which he had been born. As a result, he spent nine weeks in a complete body cast.

Toward the end of his third-grade year, doctors discovered a muscle imbalance in his eyes that prevented him from seeing the separation of words in sentences. A year of intense therapy allowed him to start learning to read. He didn't read at grade level until the seventh grade.

"He was learning-delayed because of being in the body cast and the other things going on in life," said Roseanne Stavros. "They never thought he'd be mainstreamed in school. Here he is in college. He overcame not only the physical part of all this, but also the learning disabilities he faced."

Clearly, Stavros has done more than just simply overcome multiple and significant challenges. These days, in addition to doing well in the classroom, Stavros is a key member of a Flames men's gymnastics squad that captured the 2004 Eastern College Athletic Conference championship and earned an automatic bid to the NCAA National Collegiate Men's Gymnastics Championships last spring.

Stavros' mother, a former gymnast herself, introduced him to the sport when he was 4 years old.

"I thought maybe gymnastics was something he could do and be competitive at and help his muscle development and coordination," she said.

Stavros said he stuck with gymnastics in part because it was something he was better at than most other people his age.

"My upper-body strength was so much more advanced because I was used to dragging myself across the ground, and I walked on my hands more than my feet when I was little," he said.

Ironically, Stavros didn't expect to compete at the collegiate level until he received a call from Flames head coach C. J. Johnson.

"What he has brought to the team is a Division I student-athlete who is very good in two events. He figures out ways to make himself look and do things able-bodied people can do," said Johnson. "The guys on the team don't look at him any differently. They do look at his ability. They want to beat him because they know if they can beat him, they are pretty darn good."

Stavros, who wears braces that go up to his knees on both legs, specializes in the pommel horse and still rings.

"The pommel horse is definitely my favorite apparatus," he said. "I think I have an advantage over most people because my legs are lighter than most. I swing naturally easier. I haven't mastered dismounts on the rings yet."

Stavros gives up two- to three-tenths deduction on every dismount from the still rings.

"If there's a weakness, it is his stability in landings. He can't do the flipping, twisting things, because of the lack of muscles and he can't pull his knees up. I'd say that's his biggest obstacle and he works very hard to get over it every day," said Johnson.

Stavros also has trouble pointing his toes, so he works through drills to help him keep his feet together so he looks like other competitors.

Regardless, Stavros is tough to beat, but beyond the physical, Stavros stays mentally tough as well.

"I always live by 'never give up.' As far back as I can remember, that's one of the things my dad told me. You never give up and you never say quit," Stavros said.

It is a sentiment that comes through loud and clear to those who are around the gymnast, including Johnson, who believes one of the biggest lessons teammates and others can take away from Stavros is his drive and determination.

"You can complain about every single thing in your life," he said. "Why complain when you can figure out how to do things. I think that's what Nick does best. Being differently abled doesn't change his goals at all. I think that's something to live life by."

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy