NCAA News Archive - 2005

« back to 2005 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Educators continue to fight against unwanted, unsafe and often unspoken phenomenon

|

The NCAA News

In the six years since Alfred University released survey results that showed nearly 80 percent of student-athletes are being hazed, the practice has not stopped.

Earlier this month, six current and former Frostburg State University field hockey players pleaded guilty to hazing younger teammates. The women each were fined $300, given 60-day suspended jail sentences and a year's probation for forcing teammates to drink so much alcohol that one young woman was hospitalized with a blood-alcohol level higher than four times the legal limit.

Other incidents involving athletes have occurred at NCAA member institutions across all divisions, and episodes are taking place increasingly in high schools and middle schools nationwide. The Alfred study found that hazing often involves alcohol, though in the years since that study was released, an increasing number of victims have been subjected to humiliating sexual hazing that can become violent and brutal. A number of deaths, near-deaths and serious injuries -- including in the Frostburg case -- have been reported at all levels of athletics participation. Even professional sports are not free from incidents that perpetrators often believe promote team cohesion and a sense of solidarity.

Other incidents involving athletes have occurred at NCAA member institutions across all divisions, and episodes are taking place increasingly in high schools and middle schools nationwide. The Alfred study found that hazing often involves alcohol, though in the years since that study was released, an increasing number of victims have been subjected to humiliating sexual hazing that can become violent and brutal. A number of deaths, near-deaths and serious injuries -- including in the Frostburg case -- have been reported at all levels of athletics participation. Even professional sports are not free from incidents that perpetrators often believe promote team cohesion and a sense of solidarity.

But does hazing really bring people together? Does excluding rookies and recruits initially in order to include them later on really work?

Susan Lipkins, a New York psychologist and author of "The Perfect Storm: Theory of Hazardous Hazing," told a group at the National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics convention earlier this year that hazing is ingrained in the human psyche, dating back to prehistoric times when people banded together for safety reasons.

"At some point, it became biologically necessary to distinguish those who would benefit the group and those who would put a drain on the group," she said. "Proving oneself became part of the admission process."

Lipkins said many believe that proving oneself through hazing rituals increases the bond between group members and solidifies an "us versus them" mentality already prevalent in athletics. Once an athlete has been hazed, he or she is more likely to participate in hazing activities later on, she said, calling it a "repetition compulsion." Repeating the behavior gives former victims a feeling of power or control over what happened to them.

Hank Nuwer, an assistant professor at Franklin College and author of numerous essays and books on hazing, said he student-athletes and others who haze don't think too much about their actions.

Hank Nuwer, an assistant professor at Franklin College and author of numerous essays and books on hazing, said he student-athletes and others who haze don't think too much about their actions.

"There's a feeling that there's an entitlement with this once-a-year, good, old-fashioned rout," he said, agreeing that hazing dates back long before organized athletics. "They used to have these wild nights in Europe where people just would take leave of their senses for one day, almost with the rationalization that we work hard, we party hard. This is just something we do."

Since the release of the Alfred study, which shocked many in the athletics world into action, education efforts have, in some instances, stepped up. The NCAA has teamed with national Greek organizations and with a private speaker agency to plan and execute annual symposiums about hazing and the first-ever National Hazing Prevention Week, recognized September 26-30 on campuses nationwide (see story on page A4).

Elizabeth Allan, an assistant professor at the University of Maine, Orono, who is conducting extensive research into hazing among college students, will be part of November symposium. Allan also has spoken on the topic for various groups, including at the NACDA convention in June. She noted that six years after the Alfred study, hazing still is occurring and in fact may be getting worse.

"Why isn't it changing? People know there are a lot of problems that go along with this, including bad press, litigation involving lots of money and precious time, the loss of students with talent," Allan said. "It's a team culture of abuse that leads to other kinds of problems. It leads to mistrust, which harms emotional bonds, and it causes physical harm and even death at its most extreme."

Creating a clear definition of hazing has been a struggle for those fighting the practice, and relaying that definition to student-athletes so that they understand that what may seem like a harmless activity to them actually is considered hazing. Many studies indicate that both victims and perpetrators aren't sure what constitutes hazing, and in many cases they don't believe that what they've inflicted or felt was, in fact, hazing.

According to Nuwer, hazing occurs when members of a "high-status group" (such as student-athletes or members of other elite organizations like fraternities or sororities) "demean or put through paces newcomers or rookies."

"The rookies go through with it with the expectation that they'll give up status temporarily in order to get more power after they're through the ordeal. It's all about power and status," he said.

Allan said some young perpetrators believe that if what they are doing isn't against the law, it's not hazing. She believes hazing has three components -- it involves behavior that is humiliating, degrading and harmful; it starts out as an initiation to maintain one's full status in the group; and it can occur regardless of someone's decision to participate.

Many student-athletes don't feel as though they were hazed because they willingly participated in the activity. Whether a victim agrees to participate does not change the definition of hazing, though.

Raising awareness among student-athletes, coaches and athletics administrators is one way to fight hazing on campus, but it's not the only way. Nuwer said the "immediacy effect" of an educational speaker with a personal story to tell can be powerful and have an impact on potential hazing perpetrators.

"But that group dynamic also is powerful," he said. "When the athletes are in a peer position, it's difficult when they're with older athletes who are alums who talk about the need to keep things going or bring up their old (hazing) stories. That's very difficult. Awareness will help. But what really needs to happen is student reaction against it, where they're either outraged or they think it isn't cool."

Nuwer pointed to an Indiana University, Bloomington, student who became the leader of a similar movement in the 1920s. Branch McCracken, who went on to become a legendary Hoosier basketball coach, drew attention not just at Indiana but also nationwide for his stand against hazing in a student organization. Nuwer said change eventually will be made in the culture of hazing through a few courageous student-athletes who decide that the practice is demeaning and does not foster the solidarity it is intended to create.

The culture as a whole, however, is not prepared to make the change. While reluctant to blame the media, Nuwer pointed to television shows such as "Survivor" and its ilk that force people to do outrageous physical stunts to earn the right to continue with the rest of the group.

"Hazing fits well into that culture of humiliation," he said. "We're always pointing fingers at the media, but I think in this case, there is some imitation that we see."

Charlotte Westerhaus, NCAA vice-president for diversity and inclusion, said hazing is counterproductive to the team atmosphere, and a team's success either academically or athletically is not in any way connected to hazing rituals that perpetrators mistakenly believe build a stronger framework for accomplishment.

Charlotte Westerhaus, NCAA vice-president for diversity and inclusion, said hazing is counterproductive to the team atmosphere, and a team's success either academically or athletically is not in any way connected to hazing rituals that perpetrators mistakenly believe build a stronger framework for accomplishment.

"Hazing puts a student-athlete in a position in which they have to prove that they are worthy to be on a team. They've already done that. To get a scholarship, to gain entrance to the university, they proved they are worthy. What else do they have to prove?" Westerhaus said. "Any successful business, any successful civic organization, you're not going to find hazing there. These people understand how counterproductive it is. It's not used by professors in the classroom because they understand it doesn't enhance education. If you become a judge or a doctor or a lawyer, and you join the bar or a professional organization, you will not find hazing there. Why do people believe it enhances membership on a team?

"I am aware that hazing goes on in intercollegiate athletics. We have no evidence that it has enhanced any team in winning a national championship or any team member to succeed on the field or any individual to succeed in the classroom. It is barbaric."

The secrecy element

At least one athletics administrator experienced the horrors of hazing firsthand at his institution and now travels the country to share his story. Rick Farnham, former athletics director at the University of Vermont, was at the helm when the 1999-00 Vermont men's ice hockey season was abruptly canceled about halfway through as a result of a hazing incident and student-athletes who lied to investigators after the fact. Farnham spoke to athletics administrators at the NACDA convention in June. He said that for some student-athletes, skill or performance on the field isn't enough to prove one's worthiness to the group.

"Many believe it comes from the sacrifice of one's values and human dignity by succumbing to the team's hierarchy and allowing themselves to be humiliated and then accepted," he said. "Students need to understand that no coach in America plays somebody because they can take the hazing. It doesn't make you a better point guard because you can drink three shots of whiskey in 30 seconds or go out and steal a stop sign. ... The students need to understand that."

Farnham told the NACDA group that the culture of athletics can unwittingly create a culture that promotes hazing -- some groups are excluded or on the fringe of a team because of the widespread use of terms like 'first-string,' 'back-ups' and 'taxi team.'

"We do a lot of things that contribute to the idea that everyone is not the same," he said. "The attitude of everybody's worthiness needs to be clearly demonstrated by all team participants."

Hazing rituals often are shrouded in secrecy, with victims sworn not to tell what they had to do to be accepted or, in some cases, being too humiliated to share with anyone else what was done to them. Bringing the practice out of the shadows is one way Maine's Allan believes will stop it.

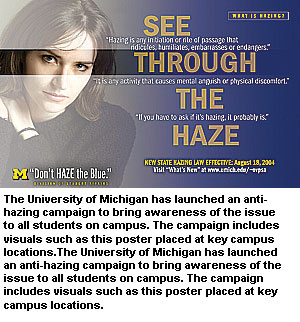

"We need to create a culture and a climate where hazing is talked about. This is one of the major problems because there is a lot of silence and secrecy about the issue," she said. She pointed to a program at the University of Michigan that is designed to educate students campus-wide about hazing.

"We need to create a culture and a climate where hazing is talked about. This is one of the major problems because there is a lot of silence and secrecy about the issue," she said. She pointed to a program at the University of Michigan that is designed to educate students campus-wide about hazing.

"They want people to think about hazing and keeping it out there in the culture. You really don't need a big budget or posters around campus to get started on this process," she said. "You can just start by talking about it. You can make it an issue at staff meetings, and make it a requirement for your coaches to talk about it with their student-athletes."

Farnham said that the student-athletes at his institution had been warned that hazing wouldn't be tolerated and could result in both expulsion from the athletics team and suspension from the university.

Since that incident in 2000 and before his retirement from the Catamounts athletics department in 2003, Farnham said Vermont implemented a "five-point program" that included requiring all student-athletes to sign a contract defining hazing, implementing clear consequences for infractions, creating a captain's leadership program and an educational program, instituting a mandatory community-service program to promote team unity, and requiring student-athletes to take a one-credit course in the life skills curriculum.

"Students need to take ownership in prevention. They must be involved in the definitions and interpretations and in educating one another about hazing," he said. "If there is going to be any success, students need to realize hazing is not about being synonymous with force, but it is the creation of an atmosphere and climate that doesn't respect everyone and take the rights of every individual into consideration."

Legislating against hazing

Sometimes, hazing prevention starts at an even higher level. According to the hazing education Web site www.stophazing.org, 44 states have anti-hazing laws. Nuwer said he thinks such laws can be effective, but not if they are applied differently in similar cases. He pointed to a disparity in application between the Frostburg State case, in which a young woman was near death and the perpetrators were given probation, and a case at an Arizona high school that was serious but not fatal or near-fatal. In that case, the perpetrators were sentenced to prison time. In other instances, schools reprimand the perpetrators and the law enforcement community does nothing.

Sometimes, hazing prevention starts at an even higher level. According to the hazing education Web site www.stophazing.org, 44 states have anti-hazing laws. Nuwer said he thinks such laws can be effective, but not if they are applied differently in similar cases. He pointed to a disparity in application between the Frostburg State case, in which a young woman was near death and the perpetrators were given probation, and a case at an Arizona high school that was serious but not fatal or near-fatal. In that case, the perpetrators were sentenced to prison time. In other instances, schools reprimand the perpetrators and the law enforcement community does nothing.

"That makes parents and community members throw up their hands when there's punishment in one area and not another," he said. "No one wants to see young people in jail with hardened criminals over these incidents, and yet at the same time you kind of wonder what the alternative is when you're talking about sexual hazing and (blood) alcohol levels over .30."

The NCAA has no written policy regarding hazing, though the Association does have a bylaw governing ethical conduct. The bylaw states that each institution is responsible for establishing sportsmanship and ethical conduct policies that are consistent with the educational mission and goals of the institution and to educate "all constituencies" about those policies. The Association also has a Committee on Sportsmanship and Ethical Conduct, which is responsible for promoting those values throughout the organization.

Westerhaus said that the national office will support each individual institution in dealing with the issue.

"I can think of no campus that endorses hazing," she said. "I look forward to working with institutions to support what they are doing and to highlight best practices. I know of no commissioner, no athletics director and no coach who supports (hazing)."

Mary Wilfert, assistant director for education services and staff liaison to the Committee on Sportsmanship and Ethical Conduct, delivered a presentation at the Faculty Athletics Representatives Association Fall Forum in November 2004. She shared a list of activities FARs could institute on their campuses to prevent and fight against hazing, including conducting coaches training; establishing clear policies with identifiable consequences; reviewing traditions, rites and rituals; and creating an accountability process for various groups.

Over the years, the Association also has addressed the issue through its CHAMPS/Life Skills program, student-athlete leadership conferences, initiative grants, speakers grants and the Citizenship through Sportsmanship Alliance.

Behaviors associated with hazing

For the first time, the NCAA drug-use survey, conducted every four years in the fall and released the following year, included questions about hazing in the version released in 2005. Fewer than 10 percent of all student-athletes indicated they had been hazed in their college sports program. Similar numbers reported actually inflicting hazing rituals on teammates.

However, of those who said they had been hazed and those who hazed their teammates, the vast majority in both groups said the hazing involved alcohol -- more than 50 percent. The survey also indicated that more women used alcohol in hazing activities than men.

Nuwer said he believes NCAA public service announcements touting student-athletes as role models and speaking out against certain issues like hazing are invaluable. However, he would like to see the organization take a firmer stand by pointing a finger at professional sports. Hazing, he said, doesn't stop once an athlete leaves the ivory tower of a college campus.

"We've got a lot of mandates at the college level, we've got a lot at the high-school level, there's a lot of coach education," he said. "There's been a tremendous jump in the last 10 years. We've got a lot of awareness there. At the pro level, it's absolutely unconscionable what they're doing. ... I think the NCAA can send a message to the pros that it's an adult sport, sports are demanding and we expect more from our athletes and we wish you would expect more, too. That means putting the burden on the commissioners of every sport. If it doesn't happen at the pro level, high-school students are going to imitate it every time."

Colleen McGlone, an assistant visiting professor at the University of New Mexico who did her doctoral dissertation on hazing among female student-athletes at Division I institutions, said she would like to see the NCAA take a firm stand against hazing (see related story, page A2). She is not alone. Nuwer agrees that an NCAA mandate would help at least get institutions under the same umbrella.

"You've got some places where it's either covered up, or people feel it's not a problem," he said. "It varies from institution to institution."

Nuwer suggested that each institution should do a "survey without punishment" of its own student-athletes similar to the Alfred study. The information would help administrators at least get a handle on what's coming, because Nuwer said he doesn't see hazing going away anytime soon. Since the Alfred study, he said anecdotal evidence points to an increase in hazing at the high-school level, especially sexual hazing and violent incidents.

"And if there's been a sexual hazing at a South Carolina high school, those students can end up in Arizona, Texas and California (as student-athletes)," he said. "The chances are that at least one of those states will have a school that could have a repetition of this."

Resources to help prevent hazing

- www.stophazing.org

- www.hazing.hanknuwer.com -- Hank Nuwer's Web site

- www.mashinc.org -- operated by Mothers Against School Hazing

- www.nhpw.com -- operated by Campuspeak to promote National Hazing Prevention Week

- www.jour.unr.edu/interactive/hazing/index.html -- created by a group of students at the University of Nevada, Reno

- http://www2.ncaa.org/legislation_and_governance/eligibility_and_conduct/sportsmanship.html -- NCAA information on sportsmanship, ethical conduct and hazing

- www.alfred.edu/sports_hazing -- 1999 study by Alfred University

- www.edc.org/hec/violence/hazing.html -- lists links to hazing resources

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy