NCAA News Archive - 2005

« back to 2005 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Institutions are clarifying line between sportsmanship and gamesmanship

|

The NCAA News

In the heat of the moment during athletics competition, student-athletes, coaches, administrators and fans sometimes behave in ways that put themselves in an unfavorable light.

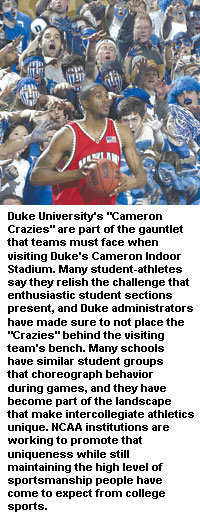

While such occurrences may be spontaneous, there is at least anecdotal evidence of premeditated actions by fans and others -- such as deliberately placing notoriously boisterous groups behind the visiting team bench or singling out players as recipients of a derisive chant -- designed to distract or even degrade the opposing team or individual players.

Indeed, people talk about the "hostile environment" teams face when they go on the road, and they emphasize the importance of the crowd as the "sixth man" that helps cheer the home team to victory. Student-athletes have said they have come to expect the challenge -- and even relish it to a degree. But is there a point at which that hostile environment changes from a sporting challenge to unsporting behavior?

Indeed, people talk about the "hostile environment" teams face when they go on the road, and they emphasize the importance of the crowd as the "sixth man" that helps cheer the home team to victory. Student-athletes have said they have come to expect the challenge -- and even relish it to a degree. But is there a point at which that hostile environment changes from a sporting challenge to unsporting behavior?

It is the latter, unsavory atmosphere that threatens the environment appropriate to intercollegiate athletics. And while that type of behavior is not by any means pervasive, NCAA member institutions are working to keep it from infiltrating the collegiate model.

That type of prevention takes common sense on the part of participants, coaches and fans, but it also requires a strong foundation of principles and guidelines to make sure high standards of sportsmanship are maintained.

Woody Gibson, director of athletics at High Point University, chairs an NCAA committee charged with helping institutions do just that.

"There are several goals when we talk about sportsmanship," said Gibson, who heads the Committee on Sportsmanship and Ethical Conduct. "One is to continue to raise awareness about sportsmanship and ethical conduct among players, coaches, fans and everyone connected with intercollegiate athletics. Another is to strongly encourage every conference to adopt guidelines that address sportsmanship and ethical conduct with all those different constituencies. That would be huge step in the right direction.

"A third goal obviously would be to enforce those guidelines."

For Gibson's group and for every institution trying to create and maintain the sportsmanlike environment, the issues span behavior both on and off the fields and courts, and it requires knowing the line between sportsmanship and gamesmanship.

The NCAA keeps a watchful eye on that line at championships events, but its oversight does not include regular-season or conference tournament play. That is where institutions can make the most difference, by encouraging their coaches and student-athletes to set a sporting example.

One Division I conference has gone so far as to adopt written principles on sportsmanship and ethical conduct that student-athletes, coaches, officials and administrators can sign at the beginning of the academic year. The Horizon League began the initiative three years ago as a way to uphold sportsmanship and build a better environment.

Jon LeCrone, the commissioner of the Horizon League, is quick to point out that his conference isn't cornering the market on the topic, but it is a model that is addressing the challenge.

When the idea was first created, signatures were required, and the measure met some resistance. LeCrone in fact said one coach refused.

"I asked why he wouldn't sign, and he said, 'This is embarrassing. We're already doing this.' I told him he missed the point," LeCrone said. "He interpreted this effort as us being critical of them for not doing something. In fact, we were asking them to just continue to do the great job they were doing. The point was to raise the awareness of the job that everyone was doing."

Members of the NCAA's Student-Athlete Advisory Committees believe having everyone sign pledges is a good step, but that it won't help if it becomes just another form.

Members of the NCAA's Student-Athlete Advisory Committees believe having everyone sign pledges is a good step, but that it won't help if it becomes just another form.

"For it to be constructive, it needs to be done at the grass-roots level by individual teams," said Andrew Baldwin, chair of the Division III SAAC. "Each team should be active in creating their personal oath to live by. If student-athletes are truly involved in creating their standards of behavior, if they choose the words and guidelines, they will be more accountable for their actions."

In the three years since the Horizon League implemented the "pledge drive," the program has become voluntary. That way, LeCrone said, anyone who signs a pledge is more likely to think about what they are putting their name to. If violations occur, there are negative consequences in the form of a public or private reprimand from LeCrone.

'Whatever it takes'

The Horizon League, whose administrators also sign the pledges, felt strongly enough about the issue to even include officials in the process.

"They have a role in managing the environment," LeCrone said. "It is how they manage our coaches and our players and sometimes how they manage fans. An ill-placed comment from an official to a coach can incite a situation. A well-placed comment can calm a coach or a player down. An official can go over to game management and say, 'I'm really having a problem with this fan in the corner and he needs to be removed.' "

Some of the rules and guidelines used in the Horizon League include not having any fans behind the goal lines of soccer matches where heckling is a problem. In basketball, Horizon League institutions are required to have a buffer zone behind the visiting bench. Those seats are reserved for visiting fans.

However, those aren't rules in some of the conferences Horizon League teams compete against in nonconference play.

"We've had some problems with fans behind the goal lines in soccer. so we eliminated that practice," said Alfreeda Goff, a senior associate commissioner with the Horizon League. "But some of our coaches feel at a disadvantage now because when they go and play at other campuses those fans are back there. So when they have teams come visit them, they feel they don't have the same home-field advantage."

"We've had some problems with fans behind the goal lines in soccer. so we eliminated that practice," said Alfreeda Goff, a senior associate commissioner with the Horizon League. "But some of our coaches feel at a disadvantage now because when they go and play at other campuses those fans are back there. So when they have teams come visit them, they feel they don't have the same home-field advantage."

The adage, "It's not whether you win or lose but how you play the game," could be applied here. The drive to win can -- and sometimes does -- threaten the once tried-and-true axiom.

"I venture to guess that not many of our intercollegiate athletes have heard of that axiom," said Sue Willey, a member and former chair of the Division II Management Council. " 'Whatever it takes' is the attitude and mentality that is accepted as long as you win."

"I venture to guess that not many of our intercollegiate athletes have heard of that axiom," said Sue Willey, a member and former chair of the Division II Management Council. " 'Whatever it takes' is the attitude and mentality that is accepted as long as you win."

Willey, the director of athletics and senior woman administrator at the University of Indianapolis, said sometimes it takes drastic efforts to change that mentality.

"In Florida, you've got parents who have to take a sportsmanship class before their kids can play," she said. "In suburban Indianapolis, you have what's called 'Silent Saturday' at soccer games. That means parents can't yell at their kids. Unfortunately, parents anymore even think they have the right to yell at other people's kids. Where does it stop? There are different groups and organizations that are trying to say, 'Hey folks; it's kind of out of control.' "

Willey has taught ethics classes on this subject, and she gave a presentation on sportsmanship at the 2003 NCAA Convention in Anaheim, California.

"The reason it's such a big issue to me is in one class when I was teaching we were talking about an ethical dilemma, and I actually had a student say, 'Dr. Willey, you're just missing it. Ethics in life are different from ethics in sports.'

"In other words," Willey said, "it's OK to steal, lie and cheat in the name of winning in sport, but you certainly wouldn't do it in real life. I contend that if you'll lie and cheat in sports, you're going to do it in life. So that got me motivated to start my sports ethics class."

While it already can be a battle to control the behavior of participants and spectators in intercollegiate sports, it doesn't help when incidents happen in high-profile venues that are then shown repeatedly through the media. The brawl among fans and players at the Indiana-Detroit NBA game last fall is a good example.

"I asked one of our men's basketball players how they felt about the incidents of poor sportsmanship in the news," said Ian Gray, chair of the Division I SAAC. "(Bronsen Schliep of the University of Nebraska, Lincoln) said, 'There is definitely a decline in humility in athletics because humility doesn't sell products. Why do you think we see controversial sports figures like Terrell Owens on SportsCenter night after night? It sells.' "

Separating fans and players

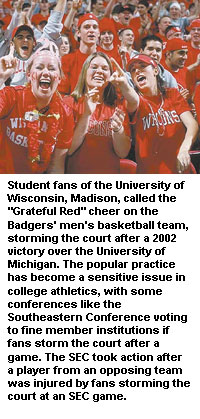

There are many examples of fans wanting to become more involved with the action on the playing surface. It has been common for fans to storm the court after big basketball victories or the football field to tear down goal posts after a high-profile game. Some fans, including students, believe it is their right to behave that way, but in fact, the behavior poses a health risk. Several people have been seriously injured in such celebrations.

But where do institutions draw the line?

On December 1, the Southeastern Conference drew it by adopting a bylaw saying that "at no time before, during or after a contest shall spectators be permitted to access to the competition area." All 12 SEC institutions agreed to the policy and a fine system was set in place.

The policy was tested when fans stormed the court after the University of South Carolina, Columbia, beat the University of Kentucky February 15. The SEC fined South Carolina $5,000, which the school's student government elected to pay.

A second offense can lead to a fine of up to $25,000 and a third offense can cost $50,000.

"We had a couple of incidences in the past in which fans stormed the field or court and there was some interaction between student-athletes and fans," said Charles Bloom, an associate commissioner for the SEC. "The athletics directors felt strongly they needed to deal with this issue."

"We had a couple of incidences in the past in which fans stormed the field or court and there was some interaction between student-athletes and fans," said Charles Bloom, an associate commissioner for the SEC. "The athletics directors felt strongly they needed to deal with this issue."

Keeping that many people off the playing< surface in a postgame celebration is a huge task, but the SEC is making it a priority.

"So much of it involves taking some pre-emptive steps, such as working with your student government, working with your dean of students and putting penalties in place for anyone who storms the field," Bloom said. "You can make sure there are consequences in place so that someone knows when they come on the field that they could face some serious penalties. If you get to the game and you don't have anything in place, it might be too late."

Fan behavior is another aspect to be considered. Institutions might be expected to control the behavior of their student-athletes, administrators and coaches, but what about fans?

Fan behavior is another aspect to be considered. Institutions might be expected to control the behavior of their student-athletes, administrators and coaches, but what about fans?

What some fans see as humorous razzing of an opponent may strike a nerve on the other side. Everyone wants to find the line where an enthusiastic atmosphere doesn't cross into profanity or obscenity.

"Having a home-team advantage has a significant impact in the outcomes of a lot of games," said Division II SAAC chair John Semeraro. "Fans are going to do some heckling. It's tough to control that. However, the line is crossed when the heckling begins to be discriminatory and inappropriate, such as talking about a student-athlete's personal life."

Institutions do have some measure of control by where they designate seating assignments.

"Everybody loves the 'Cameron Crazies' (at Duke University), but the 'Cameron Crazies' are on the other side away from the visiting bench," said Ron Stratten, NCAA vice-president for education services. "At least they didn't put the 'Cameron Crazies' down next to the opposing team's bench."

No one wants to see an athletics venue become sterile, but there should be some sense of decorum, too. Institutions are trying to strike that balance.

"We want pep bands, we want cheerleaders, and we want dance teams," LeCrone said. "We want people wearing basketballs on their heads. There is a difference between having fun in a positive way and sitting behind the visiting bench baiting, insulting or distracting the opposition. You can have a lot of fun at a game if you stay focused on your own team rather than trying to intimidate the opposition.

"That's easier said than done, particularly when you have 18-, 19- and 20-year olds in the stands."

Since an appropriate competitive atmosphere can be defined in many ways, many times it can come down to the eye of the beholder.

"It's really hard to pin down and hard to get your arms around to define it," Gibson said. "The more awareness is raised, the more people might start changing the way they view the environment."

Michelle Brutlag Hosick contributed to this

article.

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy