NCAA News Archive - 2005

« back to 2005 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Latest perception research reinforces NCAA's link with higher education

|

The NCAA News

People often talk about "moving the needle" when it comes to an organization's image perception or reputation management. In the NCAA's case, the needle being moved has been used by skeptics over the years to poke at the Association's aspiration of aligning athletics with higher education.

Indeed, the NCAA's core ideology -- governing competition in a fair, safe, equitable and sportsmanlike manner, and integrating athletics into higher education so that the educational experience of the student-athlete is paramount -- has been accepted differently over time.

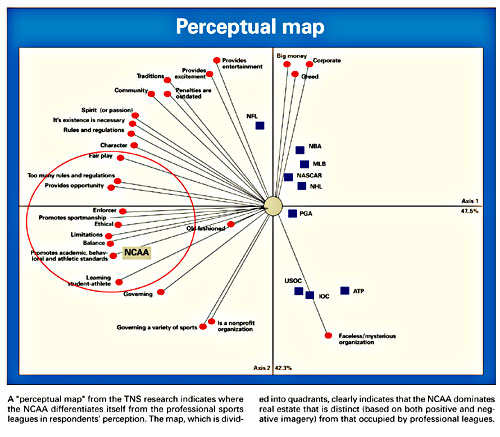

As recently as 1998, for example, research showed that the general public linked the NCAA more with big money and commercialism than with higher education. But the latest reading on the NCAA's image meter indicates less needling and more believing. The findings in fact point to a sharp increase in the public's understanding and acceptance of the NCAA mission to conduct athletics as an enhancement to -- not a substitute for -- higher education.

As recently as 1998, for example, research showed that the general public linked the NCAA more with big money and commercialism than with higher education. But the latest reading on the NCAA's image meter indicates less needling and more believing. The findings in fact point to a sharp increase in the public's understanding and acceptance of the NCAA mission to conduct athletics as an enhancement to -- not a substitute for -- higher education.

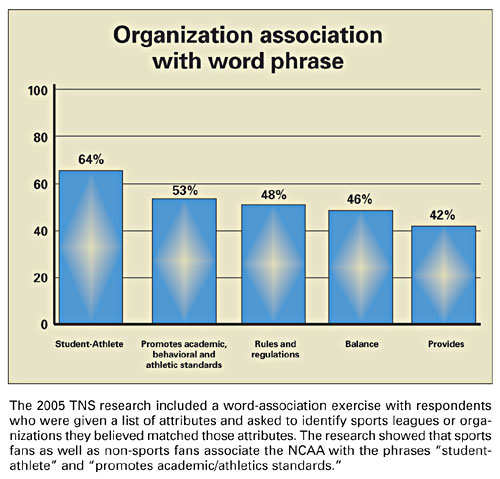

TNS Sport, a company that provides market research and media analysis on the value and impact of sports, conducted a qualitative study in February using eight focus groups of eight to 10 people each in locales ranging from Boston to Los Angeles. Quantitative research also was gleaned from 1,000 respondents to an Internet survey in March. The research targeted men and women ages 25 to 44 with at least some interest in college sports. This was a similar demographic used in previous research, so the comparatives are relevant.

Some of the "top-line" findings from the 2005 data:

- The NCAA's role remains focused on governing rules and regulations; however, the Association is now considered as being necessary to prevent chaos in intercollegiate athletics.

- The NCAA logo is highly recognizable and generates positive equity.

- The term "student-athlete" is now top of mind among respondents.

Those statements may not seem like much, but as little as three years ago the same demographic was 180 degrees from where it is today.

In 2002, public-perception research from the brand strategy firm of Landor Associates revealed respondents who saw the NCAA as having little to do with the actual education of the student. In fact, some suggested that athletes merely served the NCAA to generate money.

And four years earlier, a Lou Harris group study commissioned by the NCAA showed that the Association "was not rated highly for its effort to control the significant influence of money on college sports." Further, respondents in that study characterized the NCAA as "powerful, commercialized, greedy and arrogant, and not dynamic, open or fair."

Also consistent among previous findings was little or no knowledge from respondents about the purpose of the NCAA or its membership composition.

That is changing, though. The seven-year span of research in fact shows a seismic shift in public opinion when it comes to the Association's values and goals.

What happened?

It is no coincidence that 2002 is when the NCAA's reputation needle began its climb. That year the Association appointed a standing university president -- Myles Brand -- as its CEO, which for the first time aligned the NCAA's most influential position with the constituency assigned to assert leadership over the enterprise -- college presidents. Brand immediately established academic reform and advocacy for the values of intercollegiate athletics as his primary platforms.

In his first year alone he embarked on a whistle-stop campaign to conference meetings, governance sessions and external groups, all the while touting a reform movement that was gaining momentum through the development of tangible metrics that would hold institutions accountable for the academic success of student-athletes. At the same time, Brand established key partnerships with athletics directors, coaches, commissioners, faculty and others who in turn began to own a piece of reform and care about its success.

Brand gave the NCAA a leadership face and a voice for the press and public to recognize while reform was happening. While previous focus groups could not attach a name with the NCAA, Myles Brand's name was frequently mentioned unaided in 2005.

Brand also rallied the 1,200-member Association to contribute to an inclusive and comprehensive strategic plan. He set the plan in motion early in 2003 with data-collection sessions over a 15-month period that touched virtually every sect of the Association -- from presidents, administrators and coaches to commissioners, faculty and student-athletes.

The result was a succinct and powerful document that lays out a core ideology for the NCAA, an envisioned future, and measurable short- and long-term goals. The immediate goals were to ensure that intercollegiate athletics is integral to higher education, to enrich the student-athlete experience, to base future governance decisions on the best research available, to improve the national office administrative efforts, and to fortify the perception of the NCAA and college sports.

When the NCAA Executive Committee adopted the plan in April 2004, Brand said, "It is not a consensus document but it does reflect the directions the membership wants to pursue. The NCAA has embarked on many strategic-planning exercises in the past, but this one is different because we're actually going to implement it. This plan will put the Association in a better position than it has been in before."

Early returns support the point. At least from a reputation management perspective, the moving parts of the strategic plan have been effective.

"The Association has been successful in coordinating a consistent message since the time the strategic plan was being developed," said Dennis Cryder, the NCAA's senior vice-president for branding and communications. "We're not yet there yet and we don't have it completely refined. But if you look back over the past three years, there has been a concerted effort to focus on a common message, and that has been helping define who and what we are as an Association."

"The Association has been successful in coordinating a consistent message since the time the strategic plan was being developed," said Dennis Cryder, the NCAA's senior vice-president for branding and communications. "We're not yet there yet and we don't have it completely refined. But if you look back over the past three years, there has been a concerted effort to focus on a common message, and that has been helping define who and what we are as an Association."

The brand campaign

Such consistency is important to any organization trying to adjust its image, according to Paul Hastings of Young & Rubicam San Francisco, the creative firm the NCAA has used to help brand itself.

"The challenges include understanding the exact nature of the issues being faced and having the discipline to address them with a focused response...and being consistent with the response over a long period," Hastings said. "The solution is often one of commitment to time and consistency of message."

The most visible messaging tactic the NCAA has employed in that time has been a series of television spots with the consistent walk-out of "There are over 360,000 NCAA student-athletes -- and just about all of us are going pro in something other than sports." They have been aired primarily throughout coverage of NCAA championships on CBS Sports and ESPN, and references to them and to their tagline have been showing up in print and in conversation, indicating that various publics are getting the point.

The highly stylized ads are immediately recognizable as being the NCAA's, and they have contributed in part to the increased equity of the NCAA logo.

Other branding elements have included a consistent use of the "balance line" in NCAA publications and signage, and a more coordinated and uniform approach to using the ubiquitous NCAA blue disk. Even championship logos -- at one time a collection of visuals with varying levels of association with an NCAA event -- are being reined in under the NCAA brand umbrella.

"Through the PSAs and other messaging platforms we've been focusing on the student-athlete. It sounds so elementary to say we're going back to that very basic element, but when our research in 2002 said people don't really know who we are and what we do, we knew our creative campaign had to focus on the basics," Cryder said. "The reason we have been able to move the needle is because we had some internal discipline and a strategy that focused on who and what we are."

As to what the NCAA is, one of the elements Brand emphasized loudly early in his tenure is the need for clearly identifying the components of the organization. He said the most surprising aspect of his first year in office was how frequently people -- even the NCAA membership -- confused that aspect.

He said that depending on the discussion, "NCAA" could mean member institutions and conferences, the national office staff or a combination of all stakeholders. That confusion, Brand said, often clouds the NCAA's reputation. He established distinctions among the Association, the membership and the national office, which helped the public and media understand that NCAA policy is membership-driven.

Advocacy platforms

Not only was 2002 a milestone for NCAA leadership and the strategic plan, the Association also that year began the most unique television-rights contract in sports history -- not just college sports, but all of athletics. The 11-year "bundled-rights" agreement with CBS Sports and ESPN gave the NCAA more platforms, both print and broadcast, through which to advocate its mission over an extended period of time.

The contract in fact correlated with the NCAA positioning itself as a brand. Cryder said the NCAA had not thought of itself in terms of "brand" much before, but CBS during negotiations for the ground-breaking rights deal in 1999 said if the network was going to make that kind of investment over 11 years, it was time for the NCAA to strengthen its brand. In fact, Cryder said, the inference was that if the NCAA didn't define itself as a brand, other entities would.

"The message clearly was, 'NCAA, you need to start treating yourself as a major brand because that's how you are viewed and that's how others will market you,' " Cryder said. "In other words, CBS, ESPN and corporate America expected the NCAA to invest in itself as a brand in order to maintain and enhance the value of the NCAA assets purchased by those 'investors.' They weren't paying rights fees merely to be 'associated with' the NCAA, as was the case in sports marketing during the 1970s and 1980s."

Hastings agreed from a messaging standpoint, saying, "In today's media-intensive environment, either you take control of your image and message, or the marketplace (customers, competitors, media, detractors, advocates) will do it for you. No longer is 'staying silent' a smart option."

Ironically, though, the $6.2 billion price tag of the rights agreement upped the ante on the perception of whether the NCAA was being genuine to its academic mission. Research right after the agreement indicated a public sense that the NCAA was more about being accountants themselves than offering accounting as a major. But the TNS Sport study in 2005 did not repeat the 2002 finding that the NCAA was intent on making big money. Rather, the latest research says that the term "student-athlete" is now more often connected to higher education than to athletics.

Work remains

Because brand and reputation management is a long-term endeavor, though, there likely won't be a point even in the distant future at which the governing body of intercollegiate athletics can claim closure on a successful campaign. Indeed, though the NCAA is embarking on its Centennial year in a few months, the treatment of the NCAA as a brand has been only five years in the making. Cryder in fact says the positive research from 2005 represents more of a start than a finish.

Because brand and reputation management is a long-term endeavor, though, there likely won't be a point even in the distant future at which the governing body of intercollegiate athletics can claim closure on a successful campaign. Indeed, though the NCAA is embarking on its Centennial year in a few months, the treatment of the NCAA as a brand has been only five years in the making. Cryder in fact says the positive research from 2005 represents more of a start than a finish.

"On a scale from 1 to 10, we're probably at about a 4 on the total effort to communicate the core purpose of the Association and activate the strategic plan," he said. "To get to the 4, we've taken time to do the research, assess the state of the matter and employ a strategy. Much of the heavy lifting has been done, but there is more to do before we're at 10, or even 7 or 8."

What remains, Cryder said, is more refinement of messaging, strengthening partnerships with external constituents and building relationships even within the NCAA membership. "The biggest opportunity," he said, "is to further embrace member institutions on Goal No. 5 of the strategic plan, which is to improve the perceptions of the Association and intercollegiate athletics. The key is member institutions. It can't be the national office doing this creative campaign. It's got to be relevant to member institutions."

Hastings reinforced that goal. "It is important," he said, "that the entire organization from top to bottom understand the message, believe in it, and deliver on it through the actions of the organization as a whole, as well as each individual's actions and behavior."

That membership connection may manifest itself in next year's advertising campaign. Young & Rubicam's Tom Peck, who along with Hastings helped develop the first three iterations of the PSAs, said the promotion so far has relied on the voice of the student-athlete to connect the NCAA with higher education. A logical next step, Peck said, could include making sure people understand that the NCAA represents multiple levels of athletics emphasis.

"In other words," he said, "you can strategize or develop ads that indicate a link with higher education, but you have to explain that the NCAA is a collection of different kinds of higher education institutions. In that way, you go from 'I am the NCAA,' or the student-athlete voice, to 'we are the NCAA,' more of a membership voice. The TNS research reveals a need for the NCAA to identify who it is."

One concept under consideration, for example, is a print ad that lists a random cross section of hundreds of NCAA schools with a message at the bottom saying, "When it comes to serving the interests of the student-athlete, we're all on the same page, even if we don't all fit on one." While that is just a preliminary concept, there certainly is a desire to make the campaign more relevant to the membership.

"The NCAA must emphasize that it is a membership organization by celebrating that very membership," Cryder said. "After all, there is brand equity in being aligned with higher education, which means we need to further define the NCAA as a collection of higher education institutions. In turn, member institutions benefit by association with the collective brand of the NCAA. In that sense, the 1,200 colleges and universities own the NCAA brand -- it's their Association."

Also on the horizon this January is the launch of the NCAA Centennial, dubbed "a celebration of the student-athlete." Equity in the NCAA brand figures to be high in the Association's 100th year, and Cryder wants the NCAA to seize the branding moment and position the Association for its next century.

"Centennial celebrations typically recognize an entity's past, but there will be no better time to tout the future of the NCAA," he said. "Though the NCAA Centennial certainly will reflect on what made the Association the strong organization it is today, it will focus even more on how member institutions are developing what their Association will be tomorrow."

That is an aspiration reflected in the strategic plan as well. The "envisioned future" of the plan states a desire for intercollegiate athletics to be understood "as a valued enhancement to a quality higher education experience." Also, "Members will view their Association as an essential partner in governing intercollegiate competition and enhancing the integration of academics and athletics."

Finally, "Intercollegiate athletics will be perceived by Association members and the public as complementary to higher education. Academic success among student-athletes will enable the Association and its members to positively influence the perception of college sports."

Hastings noted that the NCAA is rightfully seeing some movement in perceptions and reputation as a result of a simple focused message that he said resonates as both sincere and truthful.

"And the NCAA has a fortunate level of targeted visibility in the marketplace," he said. "The ability and time frame for this to continue will be a result of everyone staying on message. Very often, members of an organization feel they have addressed the issue far earlier than the marketplace has taken notice. This is usually a result of being 'too close' to the issue and not appreciating the crowded media environment and the time it takes for a message to break through and gain understanding."

Perhaps future market research in years to come will support Hastings' point. At least the Association now has a good idea of how to make the needle move. Research also will be conducted to indicate movement within the media and NCAA membership.

Cryder said the game plan at least is in place.

"Like any good sports team," he said, "all that needs to be done is to execute."

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy