NCAA News Archive - 2003

« back to 2003 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Division I AAPR takes snapshot of academic progress

|

The NCAA News

First of all, Division I's AAPR is not the American Association of Retired Persons. Though the new Annual Academic Progress Rate and the organization for people over 65 share similar acronyms, the AAPR addresses a younger crowd.

Billed as part of the second phase of academic reform, the AAPR is probably lesser known than its second-phase partner -- the incentives/disincentives package. But that package doesn't have any leverage if it can't be based on data, which is where the AAPR enters the picture.

Data, which college and university presidents want to be the linchpin for reform, is what garnered their support for phase one of the overall plan -- strengthened initial-eligibility and progress-toward-degree standards that will become effective this fall. Data from the NCAA's Academic Performance Census and other sources confirmed the move toward reducing reliance on standardized test scores for initial eligibility, and for increasing annual progress requirements to give student-athletes a better chance for academic success and, ultimately, graduation.

Data also will drive the AAPR. They will have to, in fact, if the incentives/disincentives package, which could determine a team's eligibility for postseason play, hopes to be statistically and legally sound. To get there, researchers are conducting a pilot study with the help of Division I institutions that will provide a "practice" database for presidents to see how the AAPR will work.

All Division I institutions were asked to participate by submitting forms online that tracked student-athletes in one or two sports. Cumulatively, the study will compile data on about 80 programs for each of the following sports: football, men's and women's basketball, baseball, and men's and women's cross country and track. Schools provided data on eligibility, retention and graduation for six years' worth of student-athletes, including incoming and outgoing transfers, underclassmen who moved on to the pros and student-athletes who left for other reasons.

In other words, the population of the pilot study will be all student-athletes who receive athletics aid at any time during their collegiate experience. For those schools and programs that do not give aid, the pool will be all recruited student-athletes. That's a much more comprehensive pool than the federally mandated graduation-rates report tracks, and administrators expect it to provide a more accurate snapshot of a school's or program's academic performance at a given time.

The pool or population to be studied is important. If presidents want a real-time academic snapshot, and if they want to change what they see is a practice of recruiting prospects who may not intend to focus fully on their education, then data need to reflect what institutions are doing.

"If you want to change behavior, then you have to look at whom you're bringing in," said Big Ten Conference Associate Commissioner Carol Iwaoka, who is part of an NCAA team developing the AAPR.

Iwaoka and others say that examination will provide two benefits: a more accurate assessment of recruiting trends and a better pool than is provided by the current graduation-rates methodology.

"We all know how inadequate the current way the government calculates graduation rates is," said Division I Board of Directors Chair Robert Hemenway, chancellor of the University of Kansas. "There may be ways to rethink that measure, but even if you find a satisfactory way to measure graduation, it still is a multiyear measure. Therefore, we need a real-time rate that can indicate progress on an annual basis. That's why the AAPR is important."

Eligibility, retention, graduation

Once the pool is defined and the data are collected, the AAPR will become a simple point calculation based on various student-athlete outcomes during a given year or over time.

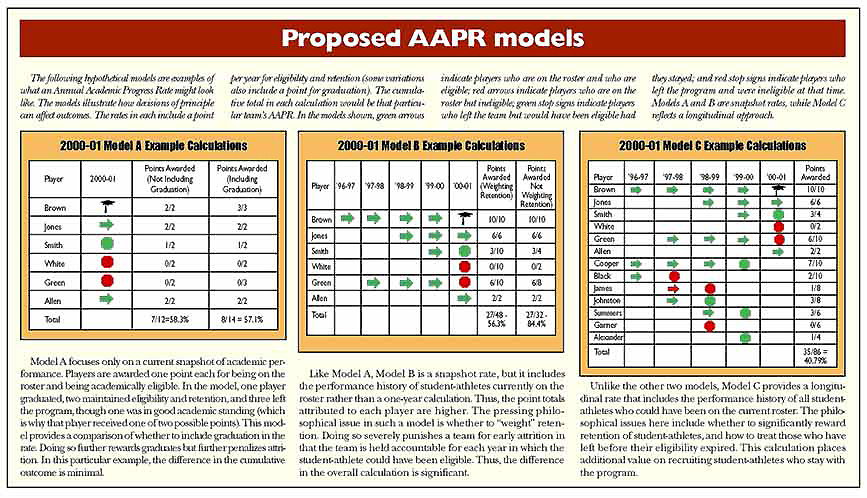

The Board of Directors Task Force, which has been the central group in the reform effort, has seen a presentation on three possible uses of the AAPR. The three models include a current snapshot of team members that records their academic progress in a given year, a current snapshot of team members that records their academic progress since joining the team and a longitudinal approach that records the entire roster over time. Each model employs a point system based on one point for each year the student-athlete is on the roster and one point for each year the player is academically eligible. Right now, the models use hypotheticals, but once the pilot study is complete, researchers will be able to manipulate real data to give insight on eligibility, player retention and graduation.

Some of the philosophical questions presidents will have to wrestle with when they determine an AAPR include how to "weight" certain variables. For example, should graduation count as an additional point above and beyond eligibility? If so, a snapshot rate would further "weight" against players who not only left the team but did not graduate. In other words, a player who leaves not only loses a point for retention but loses another point for not graduating. That could affect the overall AAPR.

Another example of "weighting" regards retention. If a student-athlete enters the team as a freshman and leaves in good academic standing after only two years, should the total possible points be four (two each for each year of eligibility and retention) or eight (two more for each year the player could have been on the roster and eligible)? In the latter case, "weighting" retention would assess a more severe penalty against that team.

Other issues include whether to have the AAPR track only current-year academic performance or performance over time. So far, presidents have not tipped their hand on which model they prefer. Kansas Chancellor Hemenway would favor some sort of combined approach.

"Whatever snapshot we select needs to demonstrate both a track record as well as a short-term academic performance," he said.

Researchers say that the snapshot rates could be averaged over several years to have a longitudinal component.

The current thinking of those developing the AAPR is that a three-year average would be desired.

"Whether you choose to look at student-athletes' academic progress each year or some longer time is worth debating," said Brit Kirwan, chancellor of the University of Maryland System. "My own view is that we need to average the success rate over several years. The current snapshot approach (Model A) suffers from the fact that there could be some anomalies that might misrepresent the reality of the academic integrity of the program, especially in sports with a small number of players. It would be better to average such a computation over several years."

Changing a culture

Whatever look the AAPR takes on, presidents want to make sure it's meaningful.

"There's such a premium on winning athletics events over the education of student-athletes that we've allowed a culture to be created that looks the other way," Kirwan said. "Well, we don't want to look the other way anymore."

Kirwan, who appointed the Board Task Force when he chaired the Board of Directors as president of Ohio State University in 2000, said the reform proposals currently on the table are "the best I've ever seen to accomplish that change."

"Simply stated, we want to reject a culture of people playing and not studying," Hemenway said. "There's a serious enough commitment on the part of presidents and chancellors that we're willing to fight whatever battles are necessary to get that done. We want a significantly improved system that has meaningful measures of academic progress."

Most who have studied the academic reform package admit that phase two -- the development of the AAPR and the incentives/disincentives package to go along with it -- might meet the most resistance. Institutions have never had to account for their teams' academic progress via the methods being proposed -- methods that might affect their participation in NCAA championships.

Kirwan believes the carrot-and-stick approach is necessary to have the intended impact.

"Restrictions on postseason play get coaches' and players' attention because it's part of the nature of high-level athletics to play to win championships," he said. "When you don't have a chance to do that, it gets everybody's attention."

"It's more than how 'tough' the AAPR might be to meet," said the Big Ten's Iwaoka. "It's about how strong the correlation is between athletics and academic reform. If you're going to set the bar so low so that anyone can jump over the candlestick, then let's not call it reform."

The AAPR team that Iwaoka serves on plans to meet again in May to review the pilot study and make preliminary recommendations. Conferences will get a chance to review those recommendations during spring meetings before the Division I Academics/Eligibility/Compliance Cabinet reviews them in June. The Division I Management Council and Board of Directors will see the proposals in July and August and be positioned to take final action as early as during their fall meetings. That could mean that an AAPR for all Division I teams might appear by spring 2004.

New progress rate must be able to withstand statistical, legal tests

One of the goals of the Annual Academic Progress Rate is to be simple and fair. Another is to be statistically and legally defensible.

Since the AAPR could be what determines which sports teams are rewarded or penalized, including whether a team plays in the NCAA tournament, the data upon which the AAPR is based should be able to withstand membership and legal scrutiny. Such scrutiny might be intense if, say, a Division I school is withheld from participating in the Division I Men's Basketball Championship and denied all the perks that come with it.

That's why the AAPR team is conducting a pilot study to gather real data upon which to make decisions about what the new progress rate should look like. Carol Iwaoka, associate commissioner of the Big Ten Conference, said data are what made phase one of academic reform plausible, and phase two should be no different.

"The graduation-rates data we've collected for years through the federal methodology has had to be given to prospects as part of the recruiting process, but other than that we haven't had to deal with similar data in the same manner as we are with the AAPR," she said. "Because this rate will be linked with incentives and disincentives, which includes the question of access, legal issues could be raised."

But most agree that the AAPR will be more sound -- and more accurate -- than the current grad-rates methodology because it will be a real-time measure and it will take into account student-athletes who leave in good academic standing or who leave for other legitimate reasons.

"The rate needs to be statistically defensible so that you don't have outcomes that stray from the purpose of enhancing academic performance," said Conference USA Commissioner Britton Banowsky, who, like Iwaoka, is a member of the AAPR working group. "And it has to be legally defensible to ensure that as you disincentivize based upon the methodology, you don't deprive someone of an asset without a strong basis."

University of Kansas Chancellor Robert Hemenway is excited about the AAPR not only because it will use sound data upon which to base the incentives and disincentives but because it could be useful even beyond its athletics element. Hemenway said done correctly, the AAPR could be used for universities to evaluate how well their fraternities and sororities are performing academically, or to compare the academic performance of ethnic, socioeconomic or other demographic groups.

"If we're careful about how we work this," Hemenway said, "we have the potential to come up with a progress rate that can be a standard measure for higher education in general, apart from whatever value it has for athletics."

Banowsky agreed, saying the AAPR will have value as "a contemporaneous management tool."

"The protracted nature of the six-year federal methodology deprives institutions of an opportunity to evaluate academic performance on an annual basis from program to program," he said.

Banowsky said that while the AAPR will be critical as part of the academic reform package, the statistical measure also will stand alone to affect behavior.

"The new methodology will be valuable in and of itself," he said, "and to the extent that some incentives and disincentives can be identified to encourage behavior, it should yield a very strong package. However, each piece independently should contribute to a better academic environment. The progress-toward-degree standards are going to change behavior. The AAPR because of the public nature of reporting will change behavior, and the incentives/disincentives piece will change behavior as well."

-- Gary T. Brown

NCAA 'graduation-success rate' among more accurate measures

In addition to the Annual Academic Progress Rate (AAPR), which will be more of a real-time snapshot of a team's academic performance, there are two other "rates" that will be involved in the academic reform package.

One is the current federally mandated graduation-rates report, which the NCAA must continue to comply with even though many people see it as an inadequate measure of academic progress. As an alternative to the federal rate, the NCAA is developing a "graduation-success rate," which is different in that it will include transfers into an institution and would allow institutions to remove student-athletes who left an institution while academically eligible from the calculation.

Thus, the two-pronged approach of an alternative to the current grad-rates methodology that doesn't penalize institutions for legitimate attrition and a more real-time measure in the AAPR gives administrators and presidents a better platform on which to base reform measures.

Preliminary recommendations regarding a new graduation-success rate may be ready later this spring. The primary challenge with developing such a rate is that there may not be a comparison group. The federal graduation-rates methodology uses the general student body at institutions as the comparison group, but the types of people included in the new graduation-success rate (transfers in good academic standing and other legitimate attrition) aren't mirrored in the student body.

"One of the things about retention with student-athletes that is different from the student body is that they have different variables controlling their continued enrollment," said Big Ten Conference Associate Commissioner Carol Iwaoka. "Pro sports attrition, impact of coaching changes and financial aid are some of those variables. Student-athletes don't control their continued enrollment the way other students do unless they have the financial resources to do it on their own."

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy