NCAA News Archive - 2002

« back to 2002 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Initial-eligibility waiver process changes red tape to green light

|

The NCAA News

People who have developed a list of colorful adjectives to describe the function of the NCAA's Initial-Eligibility Clearinghouse in recent years may have to remove "unforgiving" from their repertoire.

The reason? It's obvious.

The Clearinghouse staff and the NCAA membership services staff have found a way to significantly reduce some of the headaches of certifying initial eligibility. The process is called an "obvious" or "automatic" waiver, and it is designed to save hours of paperwork and stress for prospects who are the victims of a clerical oversight by a high school, or who fall one unit or less short of the core-course requirements but have overwhelmingly met all the other eligibility requirements.

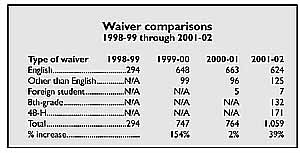

It happens more often than you would think. In 1999-00 alone, more than 750 prospects were spared the tedium of going through the normal waiver process -- which can take at least two weeks -- and had their situations rectified in a matter of days or in some cases even hours.

One of the waivers is called an automatic English waiver, which was begun in 1998-99 and really served as the impetus for others of its kind that followed. The waiver can occur when a prospect lacks one unit of English but has a high English score on the SAT or ACT (70th percentile) and a 3.300 grade-point average. Clearinghouse and NCAA staff members felt it was unnecessary to delay certification on such a prospect when it was "obvious" the case would be cleared after further review. So now in such cases, the Clearinghouse staff notifies the NCAA membership services staff, which performs a simple check that usually leads to a certification decision in less than 48 hours -- all without the prospect or the prospect's family ever knowing the case was in doubt.

Others followed

The English waiver worked so well that similar waivers were made available for prospects who had met the English requirement but were missing one or fewer units in any other core area.

Success there led to two more recent waivers that work in similar ways. One is for cases in which a prospect's eighth-grade coursework can make him or her a qualifier. The other solves cases in which high schools haven't updated their list of core courses to match what shows up on a prospect's transcripts.

In the case of the former, the waiver addresses course work the prospect took in eighth grade that wasn't considered core then but since has been added as a core course. Once the high school verifies that the course that has been added is the same one that the student took when he or she was in eighth grade, the waiver is on.

Clearinghouse Manager Ellen Wetzel said the issue of eighth-grade course work is not new. The Clearinghouse staff once was permitted to count it, but there were concerns that the practice could be open to abuse without any checkpoints in place, so it was stopped. "But now we've got the waiver process, which I still think is the best way to go," Wetzel said. "That puts some oversight safeguards in place."

Similarly, the 48-H waiver corrects cases in which there are discrepancies on what a transcript shows as a core course and what a high-school's 48-H form (the list of NCAA-approved core courses) shows.

"High schools frequently aren't getting an accurate list of core courses on the form in a timely manner," Wetzel said. "We see it all the time when we're doing final certifications -- we see courses that we know are probably core, but the school has never put them on the form.

"The waiver helps us get through that problem more expeditiously. Before that, the student would have to go through the normal waiver process."

Carolyn O'Connell, who chaired the NCAA's Initial-Eligibility Waivers Committee and its core-course subcommittee when the process was developed, calls the shortcuts "intercept waivers."

"It was a strategy put together

by the membership services staff

and the Clearinghouse designed to streamline the process not only for the member school -- but most importantly for the student-athlete," she said.

O'Connell has experienced the benefits of the process firsthand.

"I had a case in which the student was one-half unit short in English and the high school had not submitted an updated 48-H form in about five years," O'Connell said. "All the other high schools in the district had the same course included on their 48-H, so it was an oversight on the part of the high school."

The course went to the academic review committee, which approved it as a core course and notified the Clearinghouse that the course was acceptable as core. That enabled the NCAA and Clearinghouse staffs to discern that it was "obvious" that the student was a qualifier.

"And I didn't have to do any paperwork," O'Connell said. "So they 'intercepted' a situation that had remedied itself and made the student a qualifier. That took about 48 hours instead of weeks."

Extra work worth the PR

Both Wetzel and O'Connell say the process has been evolutionary, and that the evolution has come about as a result of constant communication between the Clearinghouse and NCAA staffs.

Both Wetzel and O'Connell say the process has been evolutionary, and that the evolution has come about as a result of constant communication between the Clearinghouse and NCAA staffs.

"There's been a concerted effort to refine the process for all individuals involved," O'Connell said. "The two staffs have been willing to look at how to better serve our constituents, and they've done an excellent job. They've shown a great capacity for leadership in that regard."

The fallout is that it becomes incumbent on the Clearinghouse staff to initiate the waiver, which ends up being extra work for them. Before, the staff may have suspected a problem but could only deliver a preliminary decision of uncertified and send it off to the prospect and the high school to be "their problem."

But the extra work is nothing to Wetzel and her staff as long as it's the right thing to do.

"It gets busy but it's not unmanageable," she said. "We're used to working in overdrive anyway."

And since the waivers wear the "right-thing-to-do" hat, there's a public relations benefit, as well.

"People involved with these cases have been extremely happy with the waiver," Wetzel said. "I had one urgent case we did in a day where I called the gentleman with the news and he said, 'I love you!' I've never had someone be that grateful before."

O'Connell said most of the urgent cases occur in the fall when people are making decisions about initial-eligibility status and whether the student can receive aid. In those cases, she said, time is of the essence and the waiver process is the antidote.

"In the old days of the waiver committee, our conference calls used to last more than an hour for just 15 or 20 cases," O'Connell said. "The new process is a time saver -- and it makes sense."

O'Connell also said the waivers are fairly safe from abuse. She said enough checks and balances are in place with the Clearinghouse and membership services staffs, who have established clear guidelines.

"There's no gray area," she said. "It's either a core course or it isn't. And the decisions are left to those who do this on a day-to-day basis."

Phil Grayson, an NCAA membership services representative II who indeed does do this on a day-to-day basis, said the amount of hard-copy (normal) waivers that are filed have been cut in half. More than 1,200 normal waivers were filed last year, but now that the categories for the automatic waivers have expanded, only about 700 normal waivers were filed this year and more than 900 automatic waivers were granted.

That reduces the burden on NCAA institutions to file, and it cuts what used to be a multi-member membership services contingent assigned to the task to one -- Grayson.

"Everybody wins in these cases," Grayson said. "But most importantly, it's fairer to the prospective student-athlete who by no fault of his or her own falls short of the requirements but has met the intent of the initial-eligibility standards."

Success stories point out real beneficiaries

The NCAA's "obvious" waivers have obvious beneficiaries. Not only do the waivers benefit prospective student-athletes (who rarely even know their case was in doubt), but they save paperwork and pencil pushing for administrators assigned to shepherd eligibility.

One such administrator is Linda Olson, who works in the athletics certification office at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. To put the matter in perspective, Olson related a pre-waiver case that took its toll on two schools. The prospect was a victim of his high school incorrectly omitting an English course from the 48-H form. He wasn't certified and ended up going to a Division II school, which went through the complete waiver process to make him eligible. Then after two years, he transferred to Nebraska.

"So we had to do the complete waiver, too," Olson said. "Had the automatic waiver been in place, it could have saved two schools from doing the complete waiver process and two committees from looking at it.

"So yeah, we like the new waivers."

Olson also enjoyed the beneficial flip side in a case where a prospect went through the Clearinghouse but hadn't been certified because of his test score. He enrolled at Nebraska and wanted to participate as a walk-on. Olson saw that the Algebra I course he took in eighth grade hadn't been used.

"He was sitting out the fall semester retesting because his original test score hadn't put him in the range of being eligible previously," she said. "His retest put him just a fraction outside the range, and the algebra would have given him one grade point, which was all he needed to satisfy the index. So I called the Clearinghouse, which launched the eighth-grade waiver procedure. We had him ready to go by January 1."

Jennifer Smith, assistant athletics director for compliance at Michigan State University, shares Olson's joy. She experienced a case in which a learning-disabled student in cross country went to two high schools that omitted core coursework. The ensuing waiver process had the high schools work directly with the NCAA to get the classes added on the forms.

"So instead of us doing a waiver," Smith said, "the prospect was certified in July."

Smith said the waivers not only reduce paperwork, they relieve the stress on the kids and enable them to access their scholarships at a crucial time. "Kids can't even get their books if they're not certified," she said. "Plus, a learning-disabled student can't afford to get behind. So if they can't even get their books in the first two weeks of school, then that gets them even further behind. But this way, we can get them certified in July and have their scholarship ready to pay out in August."

Success case No. 3 comes from Division II. Lynn Dorn, athletics director at North Dakota State University, related a case in which a student had a 3.05 grade-point average and a subscore of 87 on the ACT, but was missing one unit of core because of a clerical error on the part of the high school.

"It was an approved course," Dorn said, "and once we realized that we notified the NCAA on September 18 and she was approved on September 20."

Dorn said the waiver process inserts some logical control over situations that often are out of the prospects' control.

"Young students' and young athletes' destinies many times are controlled outside of their own, and in this case it just happened to be an oversight of the high school in updating their core courses," she said. "That's how simple this was."

It was obvious.

-- Gary T. Brown

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy