NCAA News Archive - 2008

« back to 2008 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

|

The NCAA News

Some of the most storied plays in college football history have occurred when the clock isn’t running.

The NCAA Football Rules Committee adopted the two-point conversion in January 1958, and in the 50 years that have followed, fans of the game have enjoyed the intrigue of the momentum-shifting play.

Former NCAA Secretary-Rules Editor John Adams said the play wasn’t even intended for the strategy it generates today; rather, the committee wanted to increase scoring and maintain the balance between offense and defense.

Adams, who has spent more than 60 years contributing to the game as an on-field official, supervisor of officials and working on the rules committee, said the idea of having a two-point conversion was first conceived in 1940. The proposal never gained enough momentum to become a rule, though, and the concept went dormant until the late 1950s when Irish Krieger, a rules committee member and a former supervisor of officials for the Big Ten Conference, resurrected the idea of giving offenses the option of gaining an extra point on the scoreboard.

At its annual meeting in 1958, the rules committee discussed the fact that scoring was down. A few members proposed moving the goalpost from the end line to the goal line to help the field-goal kicker, but that was dashed for safety concerns. “That’s when Krieger suggested the two-point conversion be considered,” Adams said. “It took the committee by surprise.”

The more it was discussed, the more momentum it gained. Influential rules committee members Dave Nelson, the first NCAA secretary-rules editor for football; legendary Oklahoma coach Bud Wilkinson; and Wallace Wade, a former coach at Alabama and Duke, helped the two-point conversion be voted in unanimously.

There was debate about the length of the try, but the group ultimately decided the two-pointer should originate from the same mark as the point-after kick (the midway point between the 2- and 3-yard lines).

The committee also added a rule stipulating that if the defense came into possession of the ball on the two-point play and somehow fumbled or ran it into its own end zone and the player was tackled behind the goal line, a one-point safety would be awarded to the offense. It’s an obscure rule that’s still in the books today, Adams said.

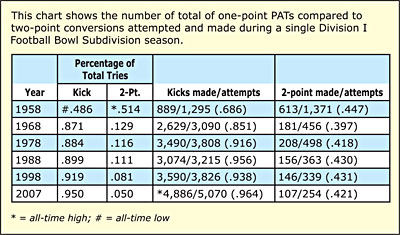

When the two-point conversion debuted in 1958, teams in what is now known as the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision opted to go for two a whopping 51.4 percent of the time. Those offenses were successful 44.7 percent of the time.

However, the following season, the concept of coaches using the two-point conversion as part of their game strategy started to take shape. The number of two-point tries dropped to 40.2 percent, and it was under 30 percent by the 1960 season.

Game-ending scenarios

Coaches continued the trend of opting for two-point conversions more judiciously in subsequent years. By 2007, FBS teams went for two only 5 percent of the time.

But it remains an integral part of the game’s strategy. Many coaches carry a reminder card about when to go for two, depending on the deficit they face or whether the additional point is advantageous to increase their lead.

And as an outcome of that strategy, there’s no substitute for the “winner-take-all” drama that the two-pointer presents. In that way, the two-pointer has factored into some of college football’s most memorable moments.

The 1984 Orange Bowl between top-ranked Nebraska and fourth-ranked Miami (Florida) is a perfect example. Nebraska was hailed as possibly the best college football team in history during the regular season, but the Cornhuskers had to defeat the Hurricanes on Miami’s home field to be voted national champions.

With Heisman Trophy winner Mike Rozier out of the game with an injury – and a third-down pass being dropped by a wide-open receiver in the end zone – Cornhuskers quarterback Turner Gill ran an option to the right on fourth-and-8. He pitched the ball to tailback Jeff Smith, who ran 24 yards for a touchdown to make the score 31-30 with 48 seconds left in the game.

Nebraska had trailed by as many as 17 points that night, and legendary Cornhuskers coach Tom Osborne had no doubt his team would go for the win instead of kicking the PAT to tie the game. Remember, there was no overtime in the FBS in those days.

The prevailing thought at the time was that a tie most likely would earn Nebraska enough votes to remain atop the polls. But Osborne wasn’t sure what was going on in the Sugar Bowl between third-ranked Auburn and eighth-ranked Michigan.

On the two-point attempt, Gill took the snap and rolled right. His pass was intended for Smith, but Miami safety Ken Calhoun tipped the ball away.

To this day, Osborne has no regrets about the decision to go for the victory.

“I assumed if you are going to win a national championship, and that’s what we felt we were playing for, that you had to win,” said Osborne, recently appointed as the director of athletics at Nebraska through summer 2010. “If you look at history, it hasn’t been kind to people who appear to settle for ties, particularly if a national championship is on the line. So we went for it.”

During preparation for the game, Osborne and his staff felt the play they ran on the two-point conversion would be a good call in a goal-to-go situation.

“We looked at a lot of film on Miami, and we felt they would be in man-to-man coverage,” said Osborne, who later guided Nebraska to three national titles in the 1990s. “Their defensive back made a good reaction and got a fingertip on it. It was probably a matter of an inch between us winning and losing the game.”

Over the years, Osborne has been complimented for making the gutsy call to go for the win.

“Most of what I heard has been positive,” said Osborne, who was 255-49-3 in 25 years at Nebraska. “But sometimes people who think you are all wet aren’t going to come up and tell you that. I’m sure there are people who disagreed with the decision. Ties are OK, but it leaves everyone a little unfulfilled.”

A more recent – and just as memorable – two-point-conversion ending occurred in the 2007 Fiesta Bowl between Boise State and Oklahoma.

After the two teams combined to score 22 points in the last 86 seconds of regulation, including a 50-yard touchdown pass by Boise State on a hook-and-ladder with seven seconds remaining, the Broncos and Sooners went to overtime.

Oklahoma’s Adrian Peterson scored on a 25-yard run on the first snap of overtime. The Sooners kicked the PAT and took a 42-35 lead.

Boise State drove to Oklahoma’s 5-yard line on its possession, where it faced fourth-and-goal. The Broncos’ Vinny Perretta faked running a sweep then lobbed a touchdown to tight end Derek Schouman to make the score 42-41.

Broncos’ coach Chris Petersen decided to go for the win instead of a kick that would force double overtime.

Broncos quarterback Jared Zabransky faked a pass to the right while putting the ball behind his back with his left hand. Tailback Ian Johnson casually took the “Statue of Liberty” handoff and raced into the left corner of the end zone for the winning points. The upset win capped an undefeated season for Boise State.

But two-point conversions don’t always transpire in winner-take-all moments.

A controversial two-point attempt late in the 1968 Ohio State-Michigan game stoked an already intense rivalry up a few notches.

With the Buckeyes leading, 50-14, in the final minutes of the game, Ohio State coach Woody Hayes kept his offense on the field for a two-point conversion after his team’s final touchdown of the day.

When asked why he went for two, Hayes replied, “Because they wouldn’t let us go for three.”