NCAA News Archive - 2007

« back to 2007 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Unlikely hero

How LSU’s Warren Morris became the Bill Mazeroski of the College World Series

How LSU’s Warren Morris became the Bill Mazeroski of the College World Series

|

By Greg Johnson

The NCAA News

The NCAA News

How rare is it for the Men’s College World Series to end on a game-winning home run in the bottom of the ninth inning?

So rare that it has happened only one time in the 60-year history of the event.

Warren Morris, the only man to know the adrenaline rush such a moment can create, now reports to duty as an investment executive for a bank in his hometown of Alexandria, Louisiana.

Even after a nine-year stint in professional baseball, including about 3½ with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Minnesota Twins and Detroit Tigers, Morris will always have a special spot in the folklore of the Louisiana State University baseball program.

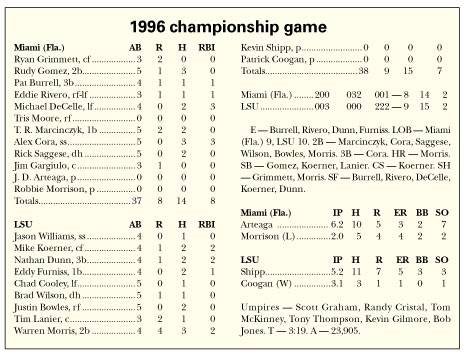

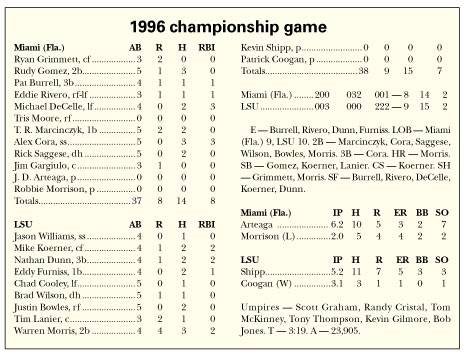

It was his two-out, two-run homer in his team’s final at-bat that gave LSU a dramatic 9-8 comeback victory over the University of Miami (Florida) in the 1996 CWS championship game. It was the third title for LSU in a string of five the Tigers won between 1990 and 2000.

Coincidentally, while with Pittsburgh, Morris was instructed by Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski, the only man to end Major League Baseball’s World Series with a home run in the bottom of the ninth of a Game 7.

The two second basemen were able to compare notes on their memorable swings. While Morris’ homer stunned Miami, Mazeroski’s blast in 1960 clinched the Pirates’ World Series win over the New York Yankees.

“There are a lot of similarities,” Morris said. “A lot of people have told him, ‘I bet when you wake up, it is the first thing on your mind.’ I would say maybe a week doesn’t go by that I don’t think about it, but I wouldn’t say I think about it every day. It is kind of unique to have someone in that same situation. I would say his was on a little larger scale.”

Skip Bertman, who coached the Tigers to all five titles and now serves as athletics director at the institution, said all of the championships have their own uniqueness about them, but Morris’ line-drive home run — his lone long ball of the season — is a defining moment for what he had to overcome during his senior year.

Beginning of a painful season

Morris began the 1995-96 academic year trying out for the U.S. Olympic Baseball Team, which Bertman coached.

He injured his right hand taking a swing during tryouts that fall and was forced to rest until spring practice began in January at LSU. In late February, the left-handed hitting Morris again felt pain after taking a swing, but doctors weren’t able to diagnose the cause.

All Morris knew is that there was no way he could take the diamond.

“It got bad enough that I would go to class and couldn’t write,” said Morris, who was an all-Southeastern Conference academic selection with a 3.5 grade-point average in zoology.

Bertman, who suspected a hamate bone injury, called an athletic trainer who worked the U.S. Olympic tryouts and was given the name of a hand specialist. The specialist returned Bertman’s call within the hour and suggested that LSU doctors perform a test to see if the hamate bone, which is located in the wrist on the same side as the little finger on a hand, was damaged.

The hook at the end of the bone stretches into the hand, and when it becomes fractured, it causes pain in the heel of the palm when a person tries to apply a grip.

After the test, a fracture was found and surgery was performed to correct the problem.

“Before that, they told me if I just rested, it would get better,” Morris said. “But it never did.”

Morris wasn’t able to return to the lineup until regional play. But even then, he was far from 100 percent.

“I had to bat him ninth, and he should’ve been batting third or fourth,” said Bertman, who guided the Tigers to CWS titles in 1991, 1993, 1996, 1997 and 2000. “But he could barely swing the bat.”

Morris poked at the ball and was able to consistently reach base anyway.

With each postseason game, he was able to take more of a normal swing.

“The best thing while we were in Omaha is the schedule is such that you get some off days,” Morris said. “That helped the healing. As corny as it sounds, the first day I felt like I could take my full swing was the batting practice the day before the championship game.”

Wild finish

With each win at Rosenblatt Stadium, the Tigers received a couple of days off while other teams were being eliminated.

The Tigers defeated Wichita State University and the University of Florida twice to set up the one-game finale against Miami.

The Hurricanes took advantage of a mistake-prone LSU team and held a 7-3 lead after six innings.

That was enough to make Bertman nervous.

“We made several misplays, base running mistakes, errors and misjudged a fly ball,” said Bertman, whose team went 22-0 that season with Morris in the lineup. “We probably should have won the game, 11-2.”

LSU scored two runs in the bottom of the seventh and eighth innings to tie the game.

Miami scored a run in the top of the ninth and called on freshman reliever Robbie Morrison to close out the game.

Though they trailed most of the game, the Tigers were confident they could find a way to win.

“Coach Bertman really instilled visualization in us and believing in ourselves and being a team of destiny,” Morris said. “I just felt that somehow, some way, we were going to come back. I never in my wildest dreams thought it would be my home run, especially since I hadn’t hit one all year.”

With one out, the Tigers had the tying run on third with No. 8 hitter Tim Lanier at the plate.

Morrison struck Lanier out with his best pitch, a slider, to set the stage for a confrontation with Morris.

The at-bat didn’t last long, because Morrison delivered another slider on the first pitch. Morris launched a line drive toward the right field wall.

“As soon as he hit it, I remember thinking, ‘This game is tied,’ ” Bertman said. “But it went out. It was hit hard, and it came on a good pitch. There was nothing the pitcher did wrong.”

Morris was thinking he had at least hit a double — replays show him running hard around first. Not until then did he thrust both fists in the air.

“The first inclination I had it was a home run was when I noticed our first base coach, Daniel Tomlin, jump about 10 feet in the air,” Morris said. “Then I started jumping, and I noticed the pain hit the Miami players, because they were on the ground. That’s when it clicked in that we won this thing.”

Morris’ teammates sprinted out of the third base dugout and mobbed the game-winning hero at home plate.

He carried the momentum of the moment on to the U.S. Olympic Baseball Team. Morris started at second base during the 1996 Atlanta Games where he hit a team-leading .409 with five home runs en route to winning a bronze medal.

“It was like they put a bionic hand on me,” said Morris, who also had a double, 10 runs scored and 11 runs batted in at the Olympics. “I had more power after the surgery than before.”

Bertman is most proud that Morris represented what it means to be a student-athlete. After Morris signed a professional contract, he came back to LSU to earn his degree.

“If there was ever a kid in my 40-year career that I wanted to have up in that situation, it would be him,” Bertman said. “That’s the part that makes it phenomenal for me.”

Morris retired from baseball after the 2005 season, but he postponed plans to enter the medical field until his 2½ -year-old twin daughters grow up a bit more. For now, he helps others plan their financial futures in his hometown about two hours from the LSU campus.

“I never had a whole lot to invest, but when I invested on my own I got some interest in it,” Morris said. “I met some people who got me looking at different things. I like it because I get to help people and get out in the community. I know a lot of people here. It has worked out.”

Perhaps he will create more memorable moments in the business world.

So rare that it has happened only one time in the 60-year history of the event.

Warren Morris, the only man to know the adrenaline rush such a moment can create, now reports to duty as an investment executive for a bank in his hometown of Alexandria, Louisiana.

Even after a nine-year stint in professional baseball, including about 3½ with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Minnesota Twins and Detroit Tigers, Morris will always have a special spot in the folklore of the Louisiana State University baseball program.

It was his two-out, two-run homer in his team’s final at-bat that gave LSU a dramatic 9-8 comeback victory over the University of Miami (Florida) in the 1996 CWS championship game. It was the third title for LSU in a string of five the Tigers won between 1990 and 2000.

Coincidentally, while with Pittsburgh, Morris was instructed by Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski, the only man to end Major League Baseball’s World Series with a home run in the bottom of the ninth of a Game 7.

The two second basemen were able to compare notes on their memorable swings. While Morris’ homer stunned Miami, Mazeroski’s blast in 1960 clinched the Pirates’ World Series win over the New York Yankees.

“There are a lot of similarities,” Morris said. “A lot of people have told him, ‘I bet when you wake up, it is the first thing on your mind.’ I would say maybe a week doesn’t go by that I don’t think about it, but I wouldn’t say I think about it every day. It is kind of unique to have someone in that same situation. I would say his was on a little larger scale.”

Skip Bertman, who coached the Tigers to all five titles and now serves as athletics director at the institution, said all of the championships have their own uniqueness about them, but Morris’ line-drive home run — his lone long ball of the season — is a defining moment for what he had to overcome during his senior year.

Beginning of a painful season

Morris began the 1995-96 academic year trying out for the U.S. Olympic Baseball Team, which Bertman coached.

He injured his right hand taking a swing during tryouts that fall and was forced to rest until spring practice began in January at LSU. In late February, the left-handed hitting Morris again felt pain after taking a swing, but doctors weren’t able to diagnose the cause.

All Morris knew is that there was no way he could take the diamond.

“It got bad enough that I would go to class and couldn’t write,” said Morris, who was an all-Southeastern Conference academic selection with a 3.5 grade-point average in zoology.

Bertman, who suspected a hamate bone injury, called an athletic trainer who worked the U.S. Olympic tryouts and was given the name of a hand specialist. The specialist returned Bertman’s call within the hour and suggested that LSU doctors perform a test to see if the hamate bone, which is located in the wrist on the same side as the little finger on a hand, was damaged.

The hook at the end of the bone stretches into the hand, and when it becomes fractured, it causes pain in the heel of the palm when a person tries to apply a grip.

After the test, a fracture was found and surgery was performed to correct the problem.

“Before that, they told me if I just rested, it would get better,” Morris said. “But it never did.”

Morris wasn’t able to return to the lineup until regional play. But even then, he was far from 100 percent.

“I had to bat him ninth, and he should’ve been batting third or fourth,” said Bertman, who guided the Tigers to CWS titles in 1991, 1993, 1996, 1997 and 2000. “But he could barely swing the bat.”

Morris poked at the ball and was able to consistently reach base anyway.

With each postseason game, he was able to take more of a normal swing.

“The best thing while we were in Omaha is the schedule is such that you get some off days,” Morris said. “That helped the healing. As corny as it sounds, the first day I felt like I could take my full swing was the batting practice the day before the championship game.”

Wild finish

With each win at Rosenblatt Stadium, the Tigers received a couple of days off while other teams were being eliminated.

The Tigers defeated Wichita State University and the University of Florida twice to set up the one-game finale against Miami.

The Hurricanes took advantage of a mistake-prone LSU team and held a 7-3 lead after six innings.

That was enough to make Bertman nervous.

“We made several misplays, base running mistakes, errors and misjudged a fly ball,” said Bertman, whose team went 22-0 that season with Morris in the lineup. “We probably should have won the game, 11-2.”

LSU scored two runs in the bottom of the seventh and eighth innings to tie the game.

Miami scored a run in the top of the ninth and called on freshman reliever Robbie Morrison to close out the game.

Though they trailed most of the game, the Tigers were confident they could find a way to win.

“Coach Bertman really instilled visualization in us and believing in ourselves and being a team of destiny,” Morris said. “I just felt that somehow, some way, we were going to come back. I never in my wildest dreams thought it would be my home run, especially since I hadn’t hit one all year.”

With one out, the Tigers had the tying run on third with No. 8 hitter Tim Lanier at the plate.

Morrison struck Lanier out with his best pitch, a slider, to set the stage for a confrontation with Morris.

The at-bat didn’t last long, because Morrison delivered another slider on the first pitch. Morris launched a line drive toward the right field wall.

“As soon as he hit it, I remember thinking, ‘This game is tied,’ ” Bertman said. “But it went out. It was hit hard, and it came on a good pitch. There was nothing the pitcher did wrong.”

Morris was thinking he had at least hit a double — replays show him running hard around first. Not until then did he thrust both fists in the air.

“The first inclination I had it was a home run was when I noticed our first base coach, Daniel Tomlin, jump about 10 feet in the air,” Morris said. “Then I started jumping, and I noticed the pain hit the Miami players, because they were on the ground. That’s when it clicked in that we won this thing.”

Morris’ teammates sprinted out of the third base dugout and mobbed the game-winning hero at home plate.

He carried the momentum of the moment on to the U.S. Olympic Baseball Team. Morris started at second base during the 1996 Atlanta Games where he hit a team-leading .409 with five home runs en route to winning a bronze medal.

“It was like they put a bionic hand on me,” said Morris, who also had a double, 10 runs scored and 11 runs batted in at the Olympics. “I had more power after the surgery than before.”

Bertman is most proud that Morris represented what it means to be a student-athlete. After Morris signed a professional contract, he came back to LSU to earn his degree.

“If there was ever a kid in my 40-year career that I wanted to have up in that situation, it would be him,” Bertman said. “That’s the part that makes it phenomenal for me.”

Morris retired from baseball after the 2005 season, but he postponed plans to enter the medical field until his 2½ -year-old twin daughters grow up a bit more. For now, he helps others plan their financial futures in his hometown about two hours from the LSU campus.

“I never had a whole lot to invest, but when I invested on my own I got some interest in it,” Morris said. “I met some people who got me looking at different things. I like it because I get to help people and get out in the community. I know a lot of people here. It has worked out.”

Perhaps he will create more memorable moments in the business world.

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy