NCAA News Archive - 2007

« back to 2007 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Research validates value, and values, of athletics

Latest studies show student-athletes satisfied with college experience

Latest studies show student-athletes satisfied with college experience

|

By Gary T. Brown

The NCAA News

The NCAA News

The percentages speak for themselves:

Eighty-eight percent of student-athletes earn their degrees.

Eighty-three percent of student-athletes have positive feelings about their choice of major.

Ninety-one percent of former Division I student-athletes have full-time jobs, and on average, their income levels are higher than non-student-athletes.

Twenty-seven percent of former Division I student-athletes go on to earn a postgraduate degree.

Falsehood? Fabrication? Fiction?

Fact, actually.

In perhaps the most ambitious and comprehensive studies yet on student-athlete experiences, the NCAA has discovered that student-athletes are at least as engaged academically as their student-body counterparts, they graduate at higher rates and they believe their athletics participation benefited their careers.

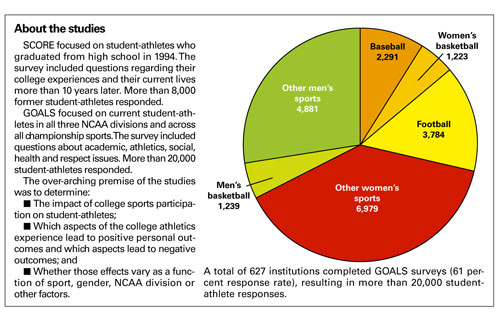

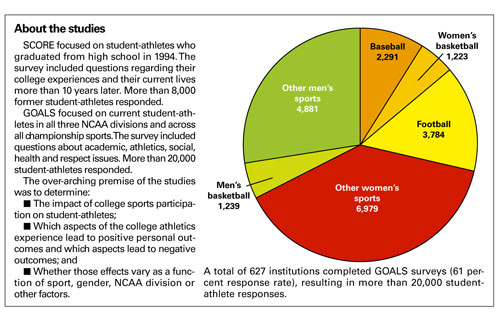

The data are from two studies — one focusing on more than 8,000 former student-athletes who entered college in 1994 (the Study of College Outcomes and Recent Experiences, or SCORE), and another spotlighting more than 20,000 current student-athletes (the Growth, Opportunities, Aspirations and Learning of Students in College, or GOALS).

Never before has such a comprehensive collection of results pointed to what most educational and intercollegiate athletics leaders already supposed — that student-athletes tend to be more successful in the classroom, and beyond, than other students, and that participation in athletics enhances their collegiate and post-educational experiences.

“These two surveys are a gold mine of data,” said NCAA President Myles Brand. “We have made a commitment in recent years to quality research as the primary driver of informed decision-making. These studies will be invaluable to us in the foreseeable future.”

“I personally believe the NCAA now has more data about the academic success of its student-athletes than any higher-education group has about the academic success of the student body at large,” said NCAA Executive Committee Chair Walter Harrison. “That’s something of which the NCAA should be proud.”

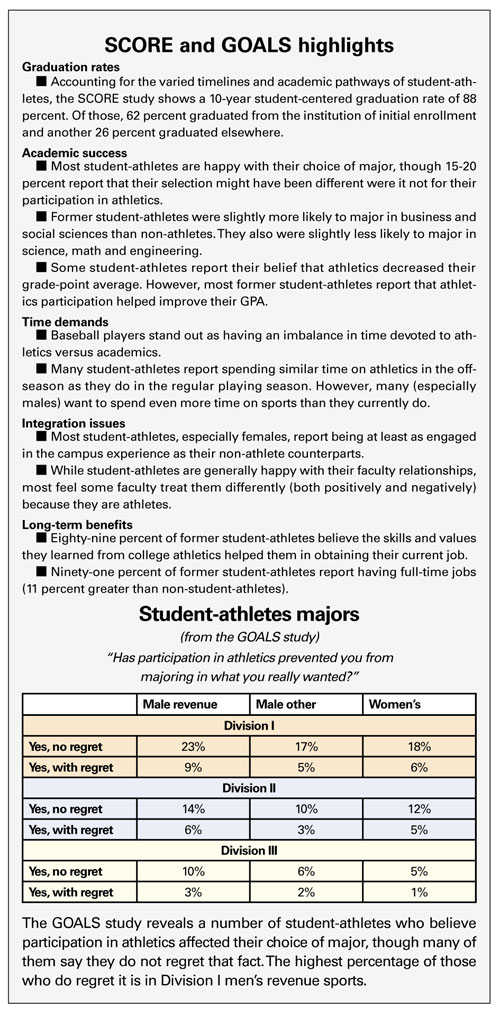

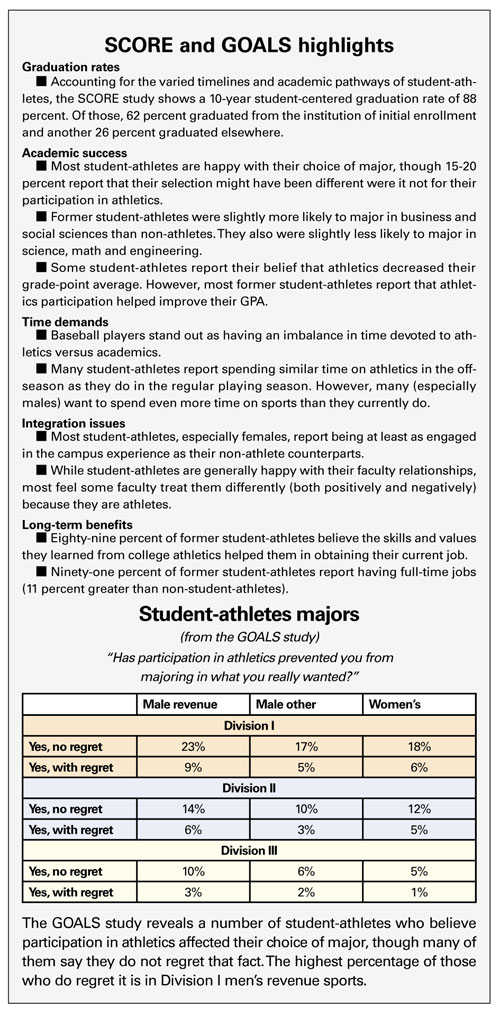

The studies reveal more good news than bad — in most cases significantly so. However, results do point to a few troubling areas. The amount of time student-athletes commit to their athletics pursuits, both in and out of season, continues to be a concern. Baseball student-athletes in particular stand out as having an imbalance in time devoted to athletics versus academics. Also, many student-athletes believe their grade-point averages would be higher if they did not participate in athletics. And a small but noteworthy percentage say they regret the interference athletics participation had on their choice of major.

Graduation success

“We’ve learned a lot about what’s good and what’s bad about college athletics and its relationship to academics, and we ought to be able to use the data from these studies to improve what we do,” said Harrison, the president at the University of Hartford. “These studies provide strong evidence, however, that we are serving our student-athletes well and also that intercollegiate athletics is part of a successful educational experience. Are there exceptions? Of course, and those are things we need to worry about, but by and large, student-athletes are benefiting from their experience in intercollegiate athletics.”

“We’ve learned a lot about what’s good and what’s bad about college athletics and its relationship to academics, and we ought to be able to use the data from these studies to improve what we do,” said Harrison, the president at the University of Hartford. “These studies provide strong evidence, however, that we are serving our student-athletes well and also that intercollegiate athletics is part of a successful educational experience. Are there exceptions? Of course, and those are things we need to worry about, but by and large, student-athletes are benefiting from their experience in intercollegiate athletics.”

Perhaps the most startling finding in either study is the 88 percent graduation rate. The SCORE study followed the entering student-athlete cohort in 1994 through a 10-year window and — accounting for the varied timelines and academic pathways of student-athletes — found that nearly nine in 10 earned a degree. Fifty-six percent graduated from the college at which they first matriculated within a five-year window. Another 6 percent earned their degree from their first college in more than five years. An additional 26 percent graduated after transferring.

“Put that in context,” Brand said. “Less than 25 percent of the American population has a baccalaureate degree, and 88 percent of student-athletes are graduating. That is quite remarkable. There is a myth that people keep repeating that athletes aren’t performing well in the classroom. You have to distinguish between ‘truthiness’ and truth and get to the facts of the matter. We’ve done that.”

The 88 percent is even higher than the NCAA’s latest Graduation Success Rate, which tracked the entering class of 1999 over a six-year period and found that 77 percent of those Division I student-athletes earned a degree. The GSR is the NCAA’s more accurate answer to the federal graduation-rate methodology that does not count transfers in good academic standing.

As good as the GSR is, though, it likely still underestimates true graduation success because it tracks only transfer movement among Division I schools. The GSR remains a better estimate of a student-centered graduation rate than the federal methodology, but the SCORE study shows that both rates underestimate true student-athlete academic success.

SCORE also indicates why graduation matters, Brand said. Over a lifetime, the financial difference between having a college education and a high school education is, on average, $1.5 million. That’s particularly significant to the student-athlete population, since the vast majority — as the tagline in the NCAA promotional campaign says — go pro in something other than sports.

“Even more interesting,” Brand said, “is that college graduates live longer. They tend to have higher earning power, which probably leads to a more comfortable and healthier lifestyle. Education is connected to longevity and health. Also, in general, 11 percent more of athletes are employed than the general population. This gives us indisputable data.”

Jack McArdle, the senior research specialist at the University of Southern California who helped administer the SCORE and GOALS studies, said the 88 percent graduation rate “may have surprised a lot of people,” but not him.

“It was no surprise to someone like me who has studied student-athlete behaviors for so many years,” said McArdle, a statistical consultant to the NCAA since 1989. “Student-athletes are hard-working people who go into a program with an outcome in mind and who get organized and see their participation in athletics as a chance to be successful in something they want to do. Even transfers had a high rate of success (80 percent) and were academically prepared when they left, which tells me that they had a positive experience at the first institution.”

The SCORE study is believed to be the first to measure graduation success over a 10-year window. While there is no student-body comparison for the GSR or the SCORE study (the Department of Education has not yet adopted a more accurate methodology that counts transfers), even student-athletes in the federal rate have graduated about two percentage points higher than their student-body counterparts for several years running.

“Even before the SCORE and GOALS studies, student-athletes haven’t been getting enough credit for their academic success, and these reports simply confirm they deserve it,” said Harrison, who also chairs the Division I Committee on Academic Performance. “While there are distinct sports within Division I we need to focus on (football, basketball, baseball) the vast majority of student-athletes outperform the general student body.”

When preliminary results of SCORE and GOALS were released at the NCAA Convention, media there focused their coverage on student-athletes who said athletics participation deterred their desired course of study. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution led with “Almost a third of Division I football and men’s basketball players say their athletics participation has prevented them from choosing the major they really wanted.” The Chronicle of Higher Education cited “one in five” in the lead sentence.

Both stories were misleading.

A ‘major’ difference

In fact, when students were asked about problems with their choice of a major, 80 percent replied “No,” 15 percent reported, “Yes, but I have no regrets,” and only 5 percent said “Yes, and I regret it.” In Division I football and men’s basketball, the percentages are 23 “yes, no regret” and 9 “yes, with regret.” Both the Constitution and Chronicle combined the “yes” answers to present a more dramatic figure without providing context.

NCAA officials understand some of that context and are looking for more. Is that 5 percent who said “with regret” a significantly negative finding?

“It depends,” said Harrison. “Is it a surprise to me or most other educators that student-athletes might choose not to major in certain fields where there are frequent afternoon labs (when they would normally be practicing)? I’m not surprised by that. I’m sure some student-athletes decide they will major in computer science instead of computer engineering because the latter has more afternoon labs.”

Brand wasn’t surprised by the 5 percent, either. He said a similar query to the general student body would probably reveal the many pressures all students face when balancing their choice of study with what their circumstances will allow. “Most people have to work through college,” he said. “Those who do are limited in their choice of major. Majors that require long labs are not easy to accommodate when you have to work — finding enough time to study isn’t easy when you have to wait tables. Intuitively, I’d be surprised if fewer than 5 percent of the general students would say they diverted their desired course of study to accommodate their life situation.”

Student-athlete have to weigh the trade-offs, too. Is the athletics scholarship and the subsequent benefit of participation in sports worth not having the full array of academic choices? According to the data, most say it is.

That answer, especially from current student-athletes under the enhanced progress-toward-degree standards, is significant for two reasons. One, it supports the values of athletics as a component of higher education, and two, it affirms that the new 40-60-80 progression of academic requirements is not as much of a deterrent to choice of major as some people suspected when the new standards were adopted with the entering class of 2003. In particular, opponents were concerned that requiring student-athletes to have completed 40 percent of their degree requirements before their third year was too much to ask. If anything, it has caused student-athletes to choose a major more quickly, but it has not tainted academic success.

McArdle said the new progress-toward-degree rules were evaluated using longitudinal data from the NCAA Academic Performance Census — data from more than 250 Division I universities resulting in more than 12,000 scholarship students per year from 1994-96, and including both graduates and nongraduates.

“Those academic records generally showed that the nongraduates had highly mixed academic trajectories, including many shifts of majors,” McArdle said. “However, the longitudinal data also showed that 95 percent of all eventual graduates would have met the thresholds of the 40-60-80 credit rules and the associated GPA requirements had they been in place at the time.”

Thus, McArdle said, the new rules were not intended to restrict the choice of a major, nor to force the major choice too rapidly. On the contrary, they were specifically based on requiring student-athletes to pattern their academic choices on the existing academic profile of most college graduates. In other words, the new standards were a more accurate indication of existing academic success patterns.

More to come

To be sure, the SCORE and GOALS studies do not reveal a utopian intercollegiate athletics environment. The NCAA sometimes is characterized as being Pollyannaish when it comes to its support of athletics as an integral part of the educational experience. While the data in this case are cause for celebration overall, NCAA officials aren’t turning a blind eye toward the bad news.

In fact, they will pursue more information about the “yes, with regret” cohort on choice of major. That is why the NCAA asked the question in the first place — it wanted to improve the student-athlete experience.

Harrison said, for example, that student-athletes deciding on their own to choose one major over another in light of their athletics time demands is one thing, but he said, “It’s quite another if you are channeled or steered into certain majors because they were easy. That would be alarming.”

McArdle said the NCAA will pursue cases where there were regrets and see what happened, especially people who didn’t graduate. He cited a higher representation of people who regretted their choice of major who then did not graduate. “That’s the group we’ll want to pursue,” he said.

Researchers also will mine the studies for sport-specific results on academic integration matters. Why, for example, does baseball grade poorly on sports versus academics? Why do some student-athletes say their grade-point averages might have been higher had they not been student-athletes? What does it mean when student-athletes say their teachers view them more as athletes than students?

The SCORE and GOALS studies are likely to provide guidance in all those cases. NCAA President Brand was right to call the research “a gold mine.” Studies that comprehensive can be sorted and structured to help with an array of challenging issues.

Overall, though, the good news significantly outweighs the concerns.

McArdle said he looked hard for the negative findings because as a researcher he likes to balance the good and bad — but the negatives were much harder to find.

“The positives were plain to see — yes, intercollegiate athletics was a great experience,” McArdle said of the results. “Now there are instances in which that is not true — some of the comments from individuals are quite negative about a particular coach or experience — but those instances are quite low. It’s not what we thought it could be — you always take a chance when you ask questions. But these questions were fair. We could have had an overwhelmingly negative response — we didn’t ask the questions in a way that forced them to answer positively. We were searching for the facts of the matter so that we could do better in the future.

“I give the NCAA credit for taking this on. No one else is asking these questions.”

And to critics who might say, “Well, what do you expect these people to say to the NCAA?”

“I appreciate that concern for GOALS (current student-athletes),” McArdle said, “since the NCAA is still their sheriff. But SCORE people have nothing to do with the NCAA anymore. With them it was simply, ‘Tell us your experiences, good and bad.’ We got hardly any bad. I’ve tried hard to be the most stringent critic, and I can’t find much wrong. That’s my surprise.”

They are the National Association of Academic Advisors for Athletics (N4A), whose members help counsel student-athletes to balance their athletics and academic pursuits. They, perhaps more than anyone, understand the context in which student-athletes make their academic choices.

To N4A President Kerry Howland, the 5 percent in the GOALS study who regretted their choice of major is low compared to what it would have been for the general student body.

“Athletics academic advisors are an asset,” she said. “It’s disappointing any time someone regrets their choice of major, but I think the percentage of such instances for the student body would be much higher.”

Howland, assistant director at the Thornton Student Life Center at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, said N4A members take pride in their ability to assess a student-athlete’s academic strengths and provide practical counsel about athletics time demands. That doesn’t mean steering student-athletes into majors they can merely handle, but finding a balance that will allow them to maximize their athletics participation without necessarily sacrificing the academic course they want to pursue.

“It’s our professional responsibility to make sure they are aware of career opportunities and test them on their strengths and priorities,” she said. “Ultimately, the student-athlete chooses his or her major, but it’s our job to be as realistic as we can. We certainly do not overtly influence the outcome, but we have to present the practicality of the situation.”

Howland’s only concern in fact is that the new 40-60-80 progress-toward-degree requirements force student-athletes to choose their academic path too quickly. Having to complete 40 percent of the requirements in a given major by the end of the sophomore year leaves little room for a change of course.

Though the 40-60-80 progression was implemented based on academic patterns of graduates, Howland said she and some of her colleagues believe it may affect student-athletes’ ability to thoroughly investigate and research majors.

“The 40 percent is a realistic benchmark, but it limits the opportunity to change your mind,” she said. “It may be OK to start in business and change to liberal arts in which you have more flexibility with electives, but if you want to do the opposite, you’re limited by the 40-60-80.”

Howland, who acknowledged that general students also face barriers when changing majors (such as prerequisites and grade-point average requirements), said some advisors worry whether every student-athlete is in “the right place developmentally” to realize how important their academic choices are so soon in their college experience. “But they do know how important their sport is to them, so they sometimes make quick decisions and don’t take full ownership of that decision,” she said. “Then later in their career when athletics is over and they didn’t achieve their professional-sports goals, perhaps they wish they had handled things differently.”

Still, that’s the kind of context Howland said is missing in discussions that categorize all student-athlete academic changes as athletics casualties.

“You have to present what you think is in the student-athlete’s best interests, given his or her priorities at the time,” she said. “There’s nothing coercive about presenting an accurate picture. We want to reach decisions based more on individual student-athletes’ capacity to learn than his or her involvement in sports. Not every regular student can major in engineering, just like not every regular student can compete in Division I intercollegiate athletics.”

Howland said some prospective athletes will choose the academic path over athletics. She cited a case in which a student who wanted to be a nurse decided her participation in sports conflicted too much with that goal, so she dropped sports.

“You have to look at advising campus by campus and student by student,” she said. “But in general, we know by student-athletes’ academic performance that they are intelligent, hard-working individuals who know their goals and understand what it takes to achieve them. And now as the NCAA research indicates, the vast majority use good judgment in making their academic decisions. In many cases, the comfort level student-athletes cite in the survey is due to an academic advisor helping them reach it.”

Eighty-eight percent of student-athletes earn their degrees.

Eighty-three percent of student-athletes have positive feelings about their choice of major.

Ninety-one percent of former Division I student-athletes have full-time jobs, and on average, their income levels are higher than non-student-athletes.

Twenty-seven percent of former Division I student-athletes go on to earn a postgraduate degree.

Falsehood? Fabrication? Fiction?

Fact, actually.

In perhaps the most ambitious and comprehensive studies yet on student-athlete experiences, the NCAA has discovered that student-athletes are at least as engaged academically as their student-body counterparts, they graduate at higher rates and they believe their athletics participation benefited their careers.

The data are from two studies — one focusing on more than 8,000 former student-athletes who entered college in 1994 (the Study of College Outcomes and Recent Experiences, or SCORE), and another spotlighting more than 20,000 current student-athletes (the Growth, Opportunities, Aspirations and Learning of Students in College, or GOALS).

Never before has such a comprehensive collection of results pointed to what most educational and intercollegiate athletics leaders already supposed — that student-athletes tend to be more successful in the classroom, and beyond, than other students, and that participation in athletics enhances their collegiate and post-educational experiences.

“These two surveys are a gold mine of data,” said NCAA President Myles Brand. “We have made a commitment in recent years to quality research as the primary driver of informed decision-making. These studies will be invaluable to us in the foreseeable future.”

“I personally believe the NCAA now has more data about the academic success of its student-athletes than any higher-education group has about the academic success of the student body at large,” said NCAA Executive Committee Chair Walter Harrison. “That’s something of which the NCAA should be proud.”

The studies reveal more good news than bad — in most cases significantly so. However, results do point to a few troubling areas. The amount of time student-athletes commit to their athletics pursuits, both in and out of season, continues to be a concern. Baseball student-athletes in particular stand out as having an imbalance in time devoted to athletics versus academics. Also, many student-athletes believe their grade-point averages would be higher if they did not participate in athletics. And a small but noteworthy percentage say they regret the interference athletics participation had on their choice of major.

Graduation success

“We’ve learned a lot about what’s good and what’s bad about college athletics and its relationship to academics, and we ought to be able to use the data from these studies to improve what we do,” said Harrison, the president at the University of Hartford. “These studies provide strong evidence, however, that we are serving our student-athletes well and also that intercollegiate athletics is part of a successful educational experience. Are there exceptions? Of course, and those are things we need to worry about, but by and large, student-athletes are benefiting from their experience in intercollegiate athletics.”

“We’ve learned a lot about what’s good and what’s bad about college athletics and its relationship to academics, and we ought to be able to use the data from these studies to improve what we do,” said Harrison, the president at the University of Hartford. “These studies provide strong evidence, however, that we are serving our student-athletes well and also that intercollegiate athletics is part of a successful educational experience. Are there exceptions? Of course, and those are things we need to worry about, but by and large, student-athletes are benefiting from their experience in intercollegiate athletics.”Perhaps the most startling finding in either study is the 88 percent graduation rate. The SCORE study followed the entering student-athlete cohort in 1994 through a 10-year window and — accounting for the varied timelines and academic pathways of student-athletes — found that nearly nine in 10 earned a degree. Fifty-six percent graduated from the college at which they first matriculated within a five-year window. Another 6 percent earned their degree from their first college in more than five years. An additional 26 percent graduated after transferring.

“Put that in context,” Brand said. “Less than 25 percent of the American population has a baccalaureate degree, and 88 percent of student-athletes are graduating. That is quite remarkable. There is a myth that people keep repeating that athletes aren’t performing well in the classroom. You have to distinguish between ‘truthiness’ and truth and get to the facts of the matter. We’ve done that.”

The 88 percent is even higher than the NCAA’s latest Graduation Success Rate, which tracked the entering class of 1999 over a six-year period and found that 77 percent of those Division I student-athletes earned a degree. The GSR is the NCAA’s more accurate answer to the federal graduation-rate methodology that does not count transfers in good academic standing.

As good as the GSR is, though, it likely still underestimates true graduation success because it tracks only transfer movement among Division I schools. The GSR remains a better estimate of a student-centered graduation rate than the federal methodology, but the SCORE study shows that both rates underestimate true student-athlete academic success.

SCORE also indicates why graduation matters, Brand said. Over a lifetime, the financial difference between having a college education and a high school education is, on average, $1.5 million. That’s particularly significant to the student-athlete population, since the vast majority — as the tagline in the NCAA promotional campaign says — go pro in something other than sports.

“Even more interesting,” Brand said, “is that college graduates live longer. They tend to have higher earning power, which probably leads to a more comfortable and healthier lifestyle. Education is connected to longevity and health. Also, in general, 11 percent more of athletes are employed than the general population. This gives us indisputable data.”

Jack McArdle, the senior research specialist at the University of Southern California who helped administer the SCORE and GOALS studies, said the 88 percent graduation rate “may have surprised a lot of people,” but not him.

“It was no surprise to someone like me who has studied student-athlete behaviors for so many years,” said McArdle, a statistical consultant to the NCAA since 1989. “Student-athletes are hard-working people who go into a program with an outcome in mind and who get organized and see their participation in athletics as a chance to be successful in something they want to do. Even transfers had a high rate of success (80 percent) and were academically prepared when they left, which tells me that they had a positive experience at the first institution.”

The SCORE study is believed to be the first to measure graduation success over a 10-year window. While there is no student-body comparison for the GSR or the SCORE study (the Department of Education has not yet adopted a more accurate methodology that counts transfers), even student-athletes in the federal rate have graduated about two percentage points higher than their student-body counterparts for several years running.

“Even before the SCORE and GOALS studies, student-athletes haven’t been getting enough credit for their academic success, and these reports simply confirm they deserve it,” said Harrison, who also chairs the Division I Committee on Academic Performance. “While there are distinct sports within Division I we need to focus on (football, basketball, baseball) the vast majority of student-athletes outperform the general student body.”

When preliminary results of SCORE and GOALS were released at the NCAA Convention, media there focused their coverage on student-athletes who said athletics participation deterred their desired course of study. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution led with “Almost a third of Division I football and men’s basketball players say their athletics participation has prevented them from choosing the major they really wanted.” The Chronicle of Higher Education cited “one in five” in the lead sentence.

Both stories were misleading.

A ‘major’ difference

In fact, when students were asked about problems with their choice of a major, 80 percent replied “No,” 15 percent reported, “Yes, but I have no regrets,” and only 5 percent said “Yes, and I regret it.” In Division I football and men’s basketball, the percentages are 23 “yes, no regret” and 9 “yes, with regret.” Both the Constitution and Chronicle combined the “yes” answers to present a more dramatic figure without providing context.

NCAA officials understand some of that context and are looking for more. Is that 5 percent who said “with regret” a significantly negative finding?

“It depends,” said Harrison. “Is it a surprise to me or most other educators that student-athletes might choose not to major in certain fields where there are frequent afternoon labs (when they would normally be practicing)? I’m not surprised by that. I’m sure some student-athletes decide they will major in computer science instead of computer engineering because the latter has more afternoon labs.”

Brand wasn’t surprised by the 5 percent, either. He said a similar query to the general student body would probably reveal the many pressures all students face when balancing their choice of study with what their circumstances will allow. “Most people have to work through college,” he said. “Those who do are limited in their choice of major. Majors that require long labs are not easy to accommodate when you have to work — finding enough time to study isn’t easy when you have to wait tables. Intuitively, I’d be surprised if fewer than 5 percent of the general students would say they diverted their desired course of study to accommodate their life situation.”

Student-athlete have to weigh the trade-offs, too. Is the athletics scholarship and the subsequent benefit of participation in sports worth not having the full array of academic choices? According to the data, most say it is.

That answer, especially from current student-athletes under the enhanced progress-toward-degree standards, is significant for two reasons. One, it supports the values of athletics as a component of higher education, and two, it affirms that the new 40-60-80 progression of academic requirements is not as much of a deterrent to choice of major as some people suspected when the new standards were adopted with the entering class of 2003. In particular, opponents were concerned that requiring student-athletes to have completed 40 percent of their degree requirements before their third year was too much to ask. If anything, it has caused student-athletes to choose a major more quickly, but it has not tainted academic success.

McArdle said the new progress-toward-degree rules were evaluated using longitudinal data from the NCAA Academic Performance Census — data from more than 250 Division I universities resulting in more than 12,000 scholarship students per year from 1994-96, and including both graduates and nongraduates.

“Those academic records generally showed that the nongraduates had highly mixed academic trajectories, including many shifts of majors,” McArdle said. “However, the longitudinal data also showed that 95 percent of all eventual graduates would have met the thresholds of the 40-60-80 credit rules and the associated GPA requirements had they been in place at the time.”

Thus, McArdle said, the new rules were not intended to restrict the choice of a major, nor to force the major choice too rapidly. On the contrary, they were specifically based on requiring student-athletes to pattern their academic choices on the existing academic profile of most college graduates. In other words, the new standards were a more accurate indication of existing academic success patterns.

More to come

To be sure, the SCORE and GOALS studies do not reveal a utopian intercollegiate athletics environment. The NCAA sometimes is characterized as being Pollyannaish when it comes to its support of athletics as an integral part of the educational experience. While the data in this case are cause for celebration overall, NCAA officials aren’t turning a blind eye toward the bad news.

In fact, they will pursue more information about the “yes, with regret” cohort on choice of major. That is why the NCAA asked the question in the first place — it wanted to improve the student-athlete experience.

Harrison said, for example, that student-athletes deciding on their own to choose one major over another in light of their athletics time demands is one thing, but he said, “It’s quite another if you are channeled or steered into certain majors because they were easy. That would be alarming.”

McArdle said the NCAA will pursue cases where there were regrets and see what happened, especially people who didn’t graduate. He cited a higher representation of people who regretted their choice of major who then did not graduate. “That’s the group we’ll want to pursue,” he said.

Researchers also will mine the studies for sport-specific results on academic integration matters. Why, for example, does baseball grade poorly on sports versus academics? Why do some student-athletes say their grade-point averages might have been higher had they not been student-athletes? What does it mean when student-athletes say their teachers view them more as athletes than students?

The SCORE and GOALS studies are likely to provide guidance in all those cases. NCAA President Brand was right to call the research “a gold mine.” Studies that comprehensive can be sorted and structured to help with an array of challenging issues.

Overall, though, the good news significantly outweighs the concerns.

McArdle said he looked hard for the negative findings because as a researcher he likes to balance the good and bad — but the negatives were much harder to find.

“The positives were plain to see — yes, intercollegiate athletics was a great experience,” McArdle said of the results. “Now there are instances in which that is not true — some of the comments from individuals are quite negative about a particular coach or experience — but those instances are quite low. It’s not what we thought it could be — you always take a chance when you ask questions. But these questions were fair. We could have had an overwhelmingly negative response — we didn’t ask the questions in a way that forced them to answer positively. We were searching for the facts of the matter so that we could do better in the future.

“I give the NCAA credit for taking this on. No one else is asking these questions.”

And to critics who might say, “Well, what do you expect these people to say to the NCAA?”

“I appreciate that concern for GOALS (current student-athletes),” McArdle said, “since the NCAA is still their sheriff. But SCORE people have nothing to do with the NCAA anymore. With them it was simply, ‘Tell us your experiences, good and bad.’ We got hardly any bad. I’ve tried hard to be the most stringent critic, and I can’t find much wrong. That’s my surprise.”

Advisors help athletes make realistic academic choices

One voice that may have been inadvertently silenced in the discussion about academic majors is that of the people appointed to help student-athletes make informed decisions. Without them, the percentage of athletes disgruntled with their choice of major would probably be much higher.

They are the National Association of Academic Advisors for Athletics (N4A), whose members help counsel student-athletes to balance their athletics and academic pursuits. They, perhaps more than anyone, understand the context in which student-athletes make their academic choices.

To N4A President Kerry Howland, the 5 percent in the GOALS study who regretted their choice of major is low compared to what it would have been for the general student body.

“Athletics academic advisors are an asset,” she said. “It’s disappointing any time someone regrets their choice of major, but I think the percentage of such instances for the student body would be much higher.”

Howland, assistant director at the Thornton Student Life Center at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, said N4A members take pride in their ability to assess a student-athlete’s academic strengths and provide practical counsel about athletics time demands. That doesn’t mean steering student-athletes into majors they can merely handle, but finding a balance that will allow them to maximize their athletics participation without necessarily sacrificing the academic course they want to pursue.

“It’s our professional responsibility to make sure they are aware of career opportunities and test them on their strengths and priorities,” she said. “Ultimately, the student-athlete chooses his or her major, but it’s our job to be as realistic as we can. We certainly do not overtly influence the outcome, but we have to present the practicality of the situation.”

Howland’s only concern in fact is that the new 40-60-80 progress-toward-degree requirements force student-athletes to choose their academic path too quickly. Having to complete 40 percent of the requirements in a given major by the end of the sophomore year leaves little room for a change of course.

Though the 40-60-80 progression was implemented based on academic patterns of graduates, Howland said she and some of her colleagues believe it may affect student-athletes’ ability to thoroughly investigate and research majors.

“The 40 percent is a realistic benchmark, but it limits the opportunity to change your mind,” she said. “It may be OK to start in business and change to liberal arts in which you have more flexibility with electives, but if you want to do the opposite, you’re limited by the 40-60-80.”

Howland, who acknowledged that general students also face barriers when changing majors (such as prerequisites and grade-point average requirements), said some advisors worry whether every student-athlete is in “the right place developmentally” to realize how important their academic choices are so soon in their college experience. “But they do know how important their sport is to them, so they sometimes make quick decisions and don’t take full ownership of that decision,” she said. “Then later in their career when athletics is over and they didn’t achieve their professional-sports goals, perhaps they wish they had handled things differently.”

Still, that’s the kind of context Howland said is missing in discussions that categorize all student-athlete academic changes as athletics casualties.

“You have to present what you think is in the student-athlete’s best interests, given his or her priorities at the time,” she said. “There’s nothing coercive about presenting an accurate picture. We want to reach decisions based more on individual student-athletes’ capacity to learn than his or her involvement in sports. Not every regular student can major in engineering, just like not every regular student can compete in Division I intercollegiate athletics.”

Howland said some prospective athletes will choose the academic path over athletics. She cited a case in which a student who wanted to be a nurse decided her participation in sports conflicted too much with that goal, so she dropped sports.

“You have to look at advising campus by campus and student by student,” she said. “But in general, we know by student-athletes’ academic performance that they are intelligent, hard-working individuals who know their goals and understand what it takes to achieve them. And now as the NCAA research indicates, the vast majority use good judgment in making their academic decisions. In many cases, the comfort level student-athletes cite in the survey is due to an academic advisor helping them reach it.”

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy