NCAA News Archive - 2007

« back to 2007 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Emerging traffic

Emerging-sports list proved invaluable to four newest NCAA championships

Emerging-sports list proved invaluable to four newest NCAA championships

|

By Michelle Brutlag Hosick

The NCAA News

The NCAA News

The 2007 Division I Women’s Rowing Championship went down to the last moment. The crowd was going crazy at the finish line, and when it was all complete, less than 2½ seconds separated the first- and fourth-place finishers in the First Eights Grand Final in May.

That battle involving Yale University and eventual champion Brown University was a great moment for rowing and women’s athletics in general — and one that might not have occurred without the concept of “emerging sports” for women.

Once rowing was listed as an emerging sport, coaches and administrators took advantage of the opportunity afforded them and nurtured the sport into the undeniable success it is today — with championships in all three divisions and broad sponsorship among the NCAA membership. That outcome is the model many emerging sports for women try to follow.

When the NCAA adopted the recommendations of its Gender-Equity Task Force in 1994, one of the biggest successes for some of the advocates on that panel was the creation of the list of emerging sports for women.

Nine sports were on that first list. In the past 13 years, some have become championship sports, while others have been added to the list. NCAA bylaws require that emerging sports must gain championship status within 10 years or show steady progress toward that goal to remain on the list. Institutions are allowed to use emerging sports to help meet the NCAA minimum sports-sponsorship requirements and minimum financial aid awards. Any sport, with proper, documented support, can self-identify as an emerging sport.

The NCAA Committee on Women’s Athletics is responsible for monitoring emerging-sport sponsorship and legislation. The CWA will address emerging sports and Olympic-sport opportunities at its upcoming meeting and look for creative ways to keep sports on the radar. Committee members plan to examine ideas from the NCAA Olympic Sports Liaison Committee for saving endangered Olympic sports, to see if any of those methods can be applied to emerging sports for women.

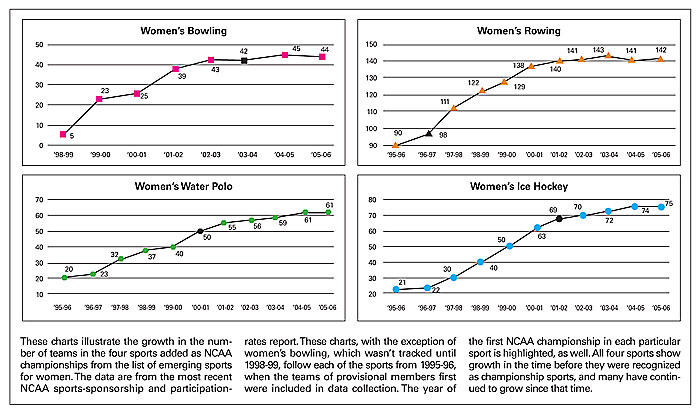

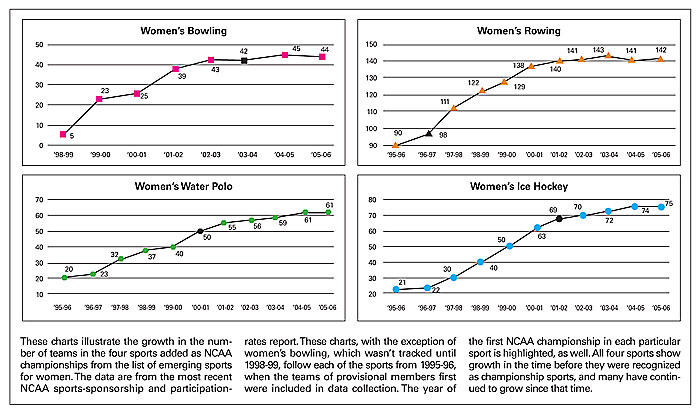

In the years since the emerging-sports list was created, four have earned full-fledged championship status. Women’s rowing, which became a National Collegiate championship in 1997 and split into championships for each division in 2002, has seen the most growth — and had the longest time to see the impact of NCAA recognition.

Women’s ice hockey and women’s water polo, which both earned NCAA championship status in the 2000-01 season, have experienced growth, too. Women’s bowling, a championship sport since 2003-04, is expected to see sponsorship numbers rise even higher in the upcoming season.

Each of those sports has grown and succeeded uniquely.

Rowing, after a decade as a championship sport, has seen the growth trickle down to the high school level, where participation has exploded. Dowling College coach Frank Pizzardi said that just on Long Island, the number of high schools sponsoring the sport has multiplied by five since rowing achieved NCAA championship status.

“They have the opportunity to compete (at the next level) now. The NCAA has made the sport more noticeable to the public,” Pizzardi said. “There were always high schools that had rowing teams, but the NCAA has helped promote the sport.”

That promotion also has improved the level of competition, said University of Tennessee, Knoxville, coach Lisa Glenn. At earlier championships, spectators would see one boat far ahead of the pack, but now, championships are decided by mere seconds.

“Overall competitiveness has greatly increased. You see a pack of boats just charging for the line, it’s more exciting,” Glenn said. “At the finish line the crowd is screaming and yelling, and you can’t hear anything coming down because the race is so close. There’s a lot of exciting competition going on because the teams are healthier and stronger.”

The way women’s rowing teams are functioning has changed, too, Glenn said, because to get to the championship, teams need a strong overall program and can’t just rely on one strong boat.

“Everybody matters. It’s a team approach to things, and the way we’ve structured the championship has made it exciting for all participants,” she said. “When you have a shot at going, you take it more seriously, and as more programs do that, then the number of viable teams increases. The programs that have been able to witness their teams competing in the championship have become excited about rowing.”

Another unique aspect of rowing — one Pizzardi believes has contributed to its popularity — is the ability of student-athletes to try out for a team without having previous experience.

“If a girl is the star on her high school basketball team but isn’t good enough to make it to the next level, she’s still an athlete. She wants to go to Tennessee. What are her chances of walking on to the basketball team or softball team? The one sport that you can still walk on to is rowing. That’s what makes it attractive,” she said. “Also, in those sports (like basketball and softball), there are some people who never get off the bench or into the game. Rowing is a sport that affords the opportunity for people to walk on and compete.”

Before the NCAA-sponsored championship, many teams aspired to participate in the Intercollegiate Rowing Association’s annual regatta, but Glenn said that was possible only for teams that could afford it. It remains popular, especially among men’s teams. For most teams, before 1997, the season ended at regional races. But the NCAA, which covers the cost of attendance for championship participants, allowed women’s rowing teams to work toward something larger at the end of the season.

“Obviously, you want to be the best at what you’re doing,” Glenn said. “This gives our programs — and rowing across the country — a way to do that.”

Glenn also said good rowers often make good students and good students make good rowers, which makes the sport an attractive option for athletics departments looking to boost their academic standing. Rowers also must be good communicators and leaders, Glenn said. Because the number of student-athletes is often high and the number of coaches is generally low, rowing student-athletes must accept accountability and responsibility for decision-making.

“There’s a quality, a unique element that’s brought to an athletics program, that adds some variety and some depth to the experience of athletics at your university when rowing is a varsity sport,” Glenn said. “These qualities are important on campus and within the athletics department as a whole.”

Glenn and Pizzardi both predicted more growth and an expansion of the championships.

“Schools are adding all the time,” Pizzardi said, pointing to two schools in Oklahoma that recently added rowing at the varsity level. “It really is a growing sport.”

Ice hockey warms up

Women’s ice hockey is also growing, with 15 teams added since the season before it was named an NCAA championship sport. As in rowing, coaches say the level of competition has risen commensurately.

“The depth of competitiveness has grown,” said Katey Stone, women’s ice hockey coach at Harvard University. “Every year, it seems like the field is more competitive.”

As the Women’s Frozen Four grows more popular, athletics directors are becoming more attracted to the sport. Institutions are investing more dollars and providing the funds necessary to field competitive programs — funds that pay for scholarships, recruiting and high-quality coaches.

“These are decisions that institutions are making to see that the sport grows. It provides an opportunity for student-athletes who otherwise wouldn’t have had that opportunity,” Stone said.

Before the NCAA championship, women’s ice hockey was largely a regional sport with conference championships, though teams did compete for a national championship during the three years before it became an NCAA championship sport. University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, coach Laura Halldorson said NCAA involvement brought the sport credibility and media attention.

Halldorson, who remembered the days when girls didn’t play ice hockey, said the first step toward legitimacy came when the Olympics added women’s ice hockey. She’s glad that the players she coaches today didn’t have to go through the discrimination against female hockey players that she experienced.

“Once women’s ice hockey was under the NCAA, it lent credibility to what we were doing. It led institutions to accelerate their eagerness to have a program,” Stone said. “For people who were out there pounding the pavement to try to get more institutions to start teams, it really helped.”

Stone said women’s ice hockey is about 10 years behind women’s basketball in some ways — most notably in fan base. She’d like to see more growth in fans and in institutions that sponsor teams.

“My dream is to walk into the arena at the Women’s Frozen Four and see 20,000 crazy hockey fans watching women play,” she said. “I’d like to see more institutions sponsor teams, especially in the Midwest. I’d like to see well-established club teams turn varsity, like at UCLA and Stanford. It would be great if women’s hockey was coast to coast.”

Water polo migration

While women’s ice hockey coaches dream of migrating their sport westward, women’s water polo coaches would like to see their sport head east. Southern California is water polo’s hotbed, but efforts are being made to promote the sport east of the Mississippi, too. For example, the University of Michigan hosted the 2005 championship.

Dan Sharadin, commissioner of the Collegiate Water Polo Association, said the sport is generally inexpensive to sponsor, so long as an institution has a swimming pool. And many pools aren’t used in the spring because no other water sports compete at that time.

The growth in women’s water polo is measured more by the size of the championship than the number of teams sponsoring the sport, though both figures have grown since 2001. In 2005, the championship grew from a four-team bracket to eight. All places in the tournament are played out, too, unlike at other championships in which a loss is an elimination.

Carin Crawford, San Diego State University women’s water polo coach, said the NCAA championship differs from other water polo experiences she had as an athlete or a coach. She said that initially, the transition from a 16-team club championship bracket sponsored by the national governing body to the four-team NCAA bracket was difficult for some in the sport to swallow. But as the championship size has doubled, the feeling is more positive.

“There is nothing quite like the excitement and the atmosphere of an NCAA championship,” Crawford said. “I feel like in any sport now I will be interested and intrigued, because when you have the chance to play for the national title, and you have the prestige and the financial backing and the commitment of an association like the NCAA, it’s great to see the student-athletes get to enjoy it and feel like first-class citizens. An NCAA championship is like nothing else in sports.”

Crawford sees water polo becoming more popular in the Southeast and Southwest, with both the University of Arizona and Arizona State University adding the sport in recent years. She would like to see growth within existing conferences so that her team could compete in the Mountain West Conference like other varsity sports at her school, instead of the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation.

While growth in the number of sponsoring institutions has plateaued for now, Sharadin predicted a resurgence. His conference has launched an initiative to help club teams make the jump to varsity status.

“We’re going to see some more growth,” he said.

Newest kid on the block

The NCAA has sponsored four women’s bowling championships, and in that time, the sport has given hope to smaller schools and schools that have never won a team championship. While powerhouse University of Nebraska, Lincoln, won the first two NCAA-sponsored bowling championships, the 2006 championship went to Fairleigh Dickinson University, Metropolitan Campus — the first team championship for a school rarely in the limelight. And in 2007, Vanderbilt University won the championship, its first team championship, as well.

Bowling can be relatively inexpensive, which makes it an attractive option for cash-strapped schools interested in adding a women’s sport. Almost every college town has a bowling alley, and equipment is minimal. Because the number of teams is so few and so spread out geographically, the biggest expense involved is traveling, said New Jersey City College coach Frank Parisi.

The number of high schools sponsoring the sport also has increased, said Vanderbilt coach Brian Reese, which helps in recruiting. Bowling adds a dimension to any institution’s program that other sports don’t have, he said.

“Athletes in nontraditional sports like bowling train as hard and as frequently as other sports. There’s a set strength and conditioning schedule they have to follow, and they follow all the academic requirements. They are treated like any other sport,” Reese said. “When you start having the success and see teams working out with other teams, the other athletes notice that the bowling team is working out just as hard as they are. That’s important.”

The bowling student-athletes at Sacred Heart University have stepped up their training schedule. Sacred Heart has sponsored bowling for 14 years, beginning as a club sport. Since the NCAA added bowling, the institution began looking at the sport differently, coach Becky Kregling said.

“We’ve got better funding. They made me a full-time coach last year. We definitely take it more seriously,” she said. “We work out a little bit more. It’s become more athletic. We look at it more in an athletic way, rather than as recreation or fun.”

Kregling said that while bowling hasn’t exploded as a sport in the last four years, the buzz is getting louder. She sees more and more e-mails from institutions looking to add the sport.

“Five years ago there was no word of anybody adding bowling,” she said. “You can be successful at a smaller school on the national level.”

While he loves competing against Divisions I and II schools, Parisi hopes eventually the championship grows enough to have separate divisional titles.

“That’s probably far down the road, but we definitely have the capability of growing, especially since the last two years the teams that have won it won the first NCAA championship for their schools,” he said. “If other schools look into how successful programs like Vanderbilt and Fairleigh Dickinson became in such a short time, you would think they would be more aggressive in starting a program.”

That battle involving Yale University and eventual champion Brown University was a great moment for rowing and women’s athletics in general — and one that might not have occurred without the concept of “emerging sports” for women.

Once rowing was listed as an emerging sport, coaches and administrators took advantage of the opportunity afforded them and nurtured the sport into the undeniable success it is today — with championships in all three divisions and broad sponsorship among the NCAA membership. That outcome is the model many emerging sports for women try to follow.

When the NCAA adopted the recommendations of its Gender-Equity Task Force in 1994, one of the biggest successes for some of the advocates on that panel was the creation of the list of emerging sports for women.

Nine sports were on that first list. In the past 13 years, some have become championship sports, while others have been added to the list. NCAA bylaws require that emerging sports must gain championship status within 10 years or show steady progress toward that goal to remain on the list. Institutions are allowed to use emerging sports to help meet the NCAA minimum sports-sponsorship requirements and minimum financial aid awards. Any sport, with proper, documented support, can self-identify as an emerging sport.

The NCAA Committee on Women’s Athletics is responsible for monitoring emerging-sport sponsorship and legislation. The CWA will address emerging sports and Olympic-sport opportunities at its upcoming meeting and look for creative ways to keep sports on the radar. Committee members plan to examine ideas from the NCAA Olympic Sports Liaison Committee for saving endangered Olympic sports, to see if any of those methods can be applied to emerging sports for women.

In the years since the emerging-sports list was created, four have earned full-fledged championship status. Women’s rowing, which became a National Collegiate championship in 1997 and split into championships for each division in 2002, has seen the most growth — and had the longest time to see the impact of NCAA recognition.

Women’s ice hockey and women’s water polo, which both earned NCAA championship status in the 2000-01 season, have experienced growth, too. Women’s bowling, a championship sport since 2003-04, is expected to see sponsorship numbers rise even higher in the upcoming season.

Each of those sports has grown and succeeded uniquely.

Rowing, after a decade as a championship sport, has seen the growth trickle down to the high school level, where participation has exploded. Dowling College coach Frank Pizzardi said that just on Long Island, the number of high schools sponsoring the sport has multiplied by five since rowing achieved NCAA championship status.

“They have the opportunity to compete (at the next level) now. The NCAA has made the sport more noticeable to the public,” Pizzardi said. “There were always high schools that had rowing teams, but the NCAA has helped promote the sport.”

That promotion also has improved the level of competition, said University of Tennessee, Knoxville, coach Lisa Glenn. At earlier championships, spectators would see one boat far ahead of the pack, but now, championships are decided by mere seconds.

“Overall competitiveness has greatly increased. You see a pack of boats just charging for the line, it’s more exciting,” Glenn said. “At the finish line the crowd is screaming and yelling, and you can’t hear anything coming down because the race is so close. There’s a lot of exciting competition going on because the teams are healthier and stronger.”

The way women’s rowing teams are functioning has changed, too, Glenn said, because to get to the championship, teams need a strong overall program and can’t just rely on one strong boat.

“Everybody matters. It’s a team approach to things, and the way we’ve structured the championship has made it exciting for all participants,” she said. “When you have a shot at going, you take it more seriously, and as more programs do that, then the number of viable teams increases. The programs that have been able to witness their teams competing in the championship have become excited about rowing.”

Another unique aspect of rowing — one Pizzardi believes has contributed to its popularity — is the ability of student-athletes to try out for a team without having previous experience.

“If a girl is the star on her high school basketball team but isn’t good enough to make it to the next level, she’s still an athlete. She wants to go to Tennessee. What are her chances of walking on to the basketball team or softball team? The one sport that you can still walk on to is rowing. That’s what makes it attractive,” she said. “Also, in those sports (like basketball and softball), there are some people who never get off the bench or into the game. Rowing is a sport that affords the opportunity for people to walk on and compete.”

Before the NCAA-sponsored championship, many teams aspired to participate in the Intercollegiate Rowing Association’s annual regatta, but Glenn said that was possible only for teams that could afford it. It remains popular, especially among men’s teams. For most teams, before 1997, the season ended at regional races. But the NCAA, which covers the cost of attendance for championship participants, allowed women’s rowing teams to work toward something larger at the end of the season.

“Obviously, you want to be the best at what you’re doing,” Glenn said. “This gives our programs — and rowing across the country — a way to do that.”

Glenn also said good rowers often make good students and good students make good rowers, which makes the sport an attractive option for athletics departments looking to boost their academic standing. Rowers also must be good communicators and leaders, Glenn said. Because the number of student-athletes is often high and the number of coaches is generally low, rowing student-athletes must accept accountability and responsibility for decision-making.

“There’s a quality, a unique element that’s brought to an athletics program, that adds some variety and some depth to the experience of athletics at your university when rowing is a varsity sport,” Glenn said. “These qualities are important on campus and within the athletics department as a whole.”

Glenn and Pizzardi both predicted more growth and an expansion of the championships.

“Schools are adding all the time,” Pizzardi said, pointing to two schools in Oklahoma that recently added rowing at the varsity level. “It really is a growing sport.”

Ice hockey warms up

Women’s ice hockey is also growing, with 15 teams added since the season before it was named an NCAA championship sport. As in rowing, coaches say the level of competition has risen commensurately.

“The depth of competitiveness has grown,” said Katey Stone, women’s ice hockey coach at Harvard University. “Every year, it seems like the field is more competitive.”

As the Women’s Frozen Four grows more popular, athletics directors are becoming more attracted to the sport. Institutions are investing more dollars and providing the funds necessary to field competitive programs — funds that pay for scholarships, recruiting and high-quality coaches.

“These are decisions that institutions are making to see that the sport grows. It provides an opportunity for student-athletes who otherwise wouldn’t have had that opportunity,” Stone said.

Before the NCAA championship, women’s ice hockey was largely a regional sport with conference championships, though teams did compete for a national championship during the three years before it became an NCAA championship sport. University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, coach Laura Halldorson said NCAA involvement brought the sport credibility and media attention.

Halldorson, who remembered the days when girls didn’t play ice hockey, said the first step toward legitimacy came when the Olympics added women’s ice hockey. She’s glad that the players she coaches today didn’t have to go through the discrimination against female hockey players that she experienced.

“Once women’s ice hockey was under the NCAA, it lent credibility to what we were doing. It led institutions to accelerate their eagerness to have a program,” Stone said. “For people who were out there pounding the pavement to try to get more institutions to start teams, it really helped.”

Stone said women’s ice hockey is about 10 years behind women’s basketball in some ways — most notably in fan base. She’d like to see more growth in fans and in institutions that sponsor teams.

“My dream is to walk into the arena at the Women’s Frozen Four and see 20,000 crazy hockey fans watching women play,” she said. “I’d like to see more institutions sponsor teams, especially in the Midwest. I’d like to see well-established club teams turn varsity, like at UCLA and Stanford. It would be great if women’s hockey was coast to coast.”

Water polo migration

While women’s ice hockey coaches dream of migrating their sport westward, women’s water polo coaches would like to see their sport head east. Southern California is water polo’s hotbed, but efforts are being made to promote the sport east of the Mississippi, too. For example, the University of Michigan hosted the 2005 championship.

Dan Sharadin, commissioner of the Collegiate Water Polo Association, said the sport is generally inexpensive to sponsor, so long as an institution has a swimming pool. And many pools aren’t used in the spring because no other water sports compete at that time.

The growth in women’s water polo is measured more by the size of the championship than the number of teams sponsoring the sport, though both figures have grown since 2001. In 2005, the championship grew from a four-team bracket to eight. All places in the tournament are played out, too, unlike at other championships in which a loss is an elimination.

Carin Crawford, San Diego State University women’s water polo coach, said the NCAA championship differs from other water polo experiences she had as an athlete or a coach. She said that initially, the transition from a 16-team club championship bracket sponsored by the national governing body to the four-team NCAA bracket was difficult for some in the sport to swallow. But as the championship size has doubled, the feeling is more positive.

“There is nothing quite like the excitement and the atmosphere of an NCAA championship,” Crawford said. “I feel like in any sport now I will be interested and intrigued, because when you have the chance to play for the national title, and you have the prestige and the financial backing and the commitment of an association like the NCAA, it’s great to see the student-athletes get to enjoy it and feel like first-class citizens. An NCAA championship is like nothing else in sports.”

Crawford sees water polo becoming more popular in the Southeast and Southwest, with both the University of Arizona and Arizona State University adding the sport in recent years. She would like to see growth within existing conferences so that her team could compete in the Mountain West Conference like other varsity sports at her school, instead of the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation.

While growth in the number of sponsoring institutions has plateaued for now, Sharadin predicted a resurgence. His conference has launched an initiative to help club teams make the jump to varsity status.

“We’re going to see some more growth,” he said.

Newest kid on the block

The NCAA has sponsored four women’s bowling championships, and in that time, the sport has given hope to smaller schools and schools that have never won a team championship. While powerhouse University of Nebraska, Lincoln, won the first two NCAA-sponsored bowling championships, the 2006 championship went to Fairleigh Dickinson University, Metropolitan Campus — the first team championship for a school rarely in the limelight. And in 2007, Vanderbilt University won the championship, its first team championship, as well.

Bowling can be relatively inexpensive, which makes it an attractive option for cash-strapped schools interested in adding a women’s sport. Almost every college town has a bowling alley, and equipment is minimal. Because the number of teams is so few and so spread out geographically, the biggest expense involved is traveling, said New Jersey City College coach Frank Parisi.

The number of high schools sponsoring the sport also has increased, said Vanderbilt coach Brian Reese, which helps in recruiting. Bowling adds a dimension to any institution’s program that other sports don’t have, he said.

“Athletes in nontraditional sports like bowling train as hard and as frequently as other sports. There’s a set strength and conditioning schedule they have to follow, and they follow all the academic requirements. They are treated like any other sport,” Reese said. “When you start having the success and see teams working out with other teams, the other athletes notice that the bowling team is working out just as hard as they are. That’s important.”

The bowling student-athletes at Sacred Heart University have stepped up their training schedule. Sacred Heart has sponsored bowling for 14 years, beginning as a club sport. Since the NCAA added bowling, the institution began looking at the sport differently, coach Becky Kregling said.

“We’ve got better funding. They made me a full-time coach last year. We definitely take it more seriously,” she said. “We work out a little bit more. It’s become more athletic. We look at it more in an athletic way, rather than as recreation or fun.”

Kregling said that while bowling hasn’t exploded as a sport in the last four years, the buzz is getting louder. She sees more and more e-mails from institutions looking to add the sport.

“Five years ago there was no word of anybody adding bowling,” she said. “You can be successful at a smaller school on the national level.”

While he loves competing against Divisions I and II schools, Parisi hopes eventually the championship grows enough to have separate divisional titles.

“That’s probably far down the road, but we definitely have the capability of growing, especially since the last two years the teams that have won it won the first NCAA championship for their schools,” he said. “If other schools look into how successful programs like Vanderbilt and Fairleigh Dickinson became in such a short time, you would think they would be more aggressive in starting a program.”

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy