NCAA News Archive - 2007

« back to 2007 | Back to NCAA News Archive Index

Centerpiece - Brave new media world

Advances in communication technology present opportunities, challenges

Advances in communication technology present opportunities, challenges

|

By Michelle Brutlag Hosick

The NCAA News

The NCAA News

Fifteen years ago, intercollegiate athletics departments were about to open the door to a brave new world that would forever change the way intercollegiate athletics interacted with the public.

Though the precursors to what we know today as the Internet were born in the late 1960s and early 1970s, use of the World Wide Web exploded after 1990 when restrictions on commercial use were lifted. The Internet carried audio and video for the first time in 1992. Today, the Internet, technology and its ever-expanding capabilities mean different things to different institutions and their athletics departments, depending on size, desire and capabilities.

For some institutions, technological advancements mean that even if a student-athlete’s parents live in California and the institution their son or daughter attends is in New York, those parents can still watch competition.

For other institutions, new media applications have allowed them to provide podcasts of press conferences or access to promotional television spots or even live chats with coaches and student-athletes.

Athletics departments make new media decisions based on what their audience demands — and what the institutions can afford to provide. But whether they are broadcasting every home game over the Internet or allowing a coach or athletics director to offer a few thoughts through a weekly blog, NCAA members are taking advantage of the opportunities the new media world is offering.

“The public wants everything you can give to them,” said Tim Nott, sports information director at Grand Valley State University. “In today’s society, that’s why newspapers break stories without having the right facts, because they can get beat out by the real time of the Internet. You can have it online instantly, and for a newspaper, you have to wait until tomorrow. Tomorrow’s no good anymore.”

At Arizona State University, Sports Information Director Doug Tammaro said he looks at the Sun Devils Web site as the athletics department newspaper. Where the sports information staff at Arizona State once competed with other area schools to get items into newspapers, now their Web sites compete with media juggernauts like ESPN.com and CBS Sportsline. They offer insider features the conglomerates don’t have access to — like the public service announcements about the Sun Devils athletics program or a collection of reproductions of billboards promoting an Arizona State athletics marketing campaign “Sun Devil Laws” that can be seen in person in the Phoenix area.

“You want to drive people to your Web site. It’s like your newspaper and your television station,” Tammaro said. “It’s a great way to get the word out about your team. You just have to have the people power to be able to do it.”

Use of campus resources

So how do you manage when you work on a staff with just two — or fewer — full-time sports information professionals? That is the life of most Division III and many Division II athletics department media relations offices.

Many institutions use their student population to help produce content for their athletics department Web sites. At Division III Ithaca College, the athletics department had a ready-made avenue for webcasting and broadcasting audio from competitions. With two campus radio stations and a campus television station broadcasting dozens of hours of live original programming per week, all three outlets were already actively covering athletics events. About seven or eight years ago, the stations began broadcasting through Ithaca’s Web site, a great service but one with limited availability. Eventually, the athletics department partnered with a company that could provide unlimited bandwidth and more technological capability that provides for unlimited audience potential.

Ithaca Sports Information Director Mike Warwick said it was beneficial to have two radio stations doing so many games, “but by that same token,” he said, “it kind of handcuffs us in that you can listen to all of our women’s basketball games, but you can’t listen to volleyball because they don’t choose to broadcast those. So we need to find ways to provide that kind of service to fans without having to rely on someone else on campus to actually provide it.

“It’s not because we’re not happy with (the campus stations) or we don’t appreciate it — they just can’t provide as much content as we want to be able to provide to our audience.”

To that end, more institutions like Ithaca are choosing to produce webcasts and audio broadcasts completely on their own, often with assistance from students from the institution’s communications program.

Stevens Institute of Technology launched its first full year of formal, branded webcasting with the 2006-07 academic year. Called “Duck Casts,” Warwick said the model is one he would like to emulate at Ithaca. Brian Granata, sports information director at Stevens Tech, said the Duck Casts are produced with a largely student-based staff. What started as a modest goal of producing about 30 webcasts quickly grew to 75 because of the demand.

Granata, who produced each event, trained several student producers to fill his role when he had to attend to other sports information duties. Students served as color and play-by-play announcers. They also did all the camerawork and provided graphics.

“It’s been challenging at times, but we have a talented student base that has latched on to this project,” Granata said. “It’s exciting.”

Meeting expectations

Even though the institutions might be smaller and less flush with cash than some of the larger Division I institutions, the expectations of the parents who send their children to play sports at a Division III school often are not lower than those who send their kids to a major Division I program. Warwick said that as technology has developed, people have begun to expect that certain things will be available to them.

“Because you’re dealing with parents of your student-athletes using this technology, they haven’t been parents of college athletes for 10 years like I’ve been SID for 10 years. They come into the role of being parents of college athletes and they see what technology is available, and they just expect to be able to listen to the game over the Internet,” Warwick said. “If they’re going to have that mindset, I’m glad we have the technology to be able to meet that expectation.”

Sometimes that expectation isn’t there, but institutions still can use technology to generate interest in their program among local and national audiences.

“I think at major Division I schools, there’s so much television and newspaper coverage, which brings on its own challenges, but the interest is already there and it’s going to feed itself,” Granata said. “At Division III, you’ve got to work to find new and creative outlets.”

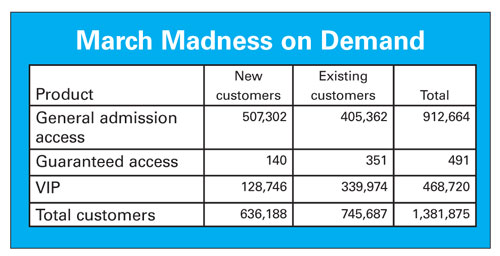

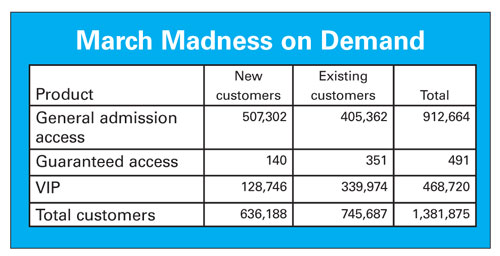

The NCAA and its corporate partners first ventured into webcasting with “March Madness On Demand” in 2003. For the first time in 2006, March Madness On Demand provided free live streams of Division I men’s basketball tournament contests (it had been a pay service before 2006). On the heels of incredible popularity in 2006, CBS Sportsline doubled the bandwidth for the project, built a live updating scoreboard into the video player, increased the viewing screen and included live radio broadcasts for the entire tournament. The network even added a halftime show.

Balancing new and old media

People responded to the product: 46 percent of the 1,381,875 users for MMOD were new in 2007 and total hours of consumption were up 28 percent.

At institutions at all levels, the Web is seen as a new area in which institutions can recruit — both student-athletes and the general student population. Tim Match, sports information director at Clemson University, said the Web has created opportunities for instantaneous feedback from all sources — positive or negative.

“The Internet provided a tremendous amount of opportunities for us to promote Clemson, and when you have more opportunities, you have to take advantage of them,” Match said. “We try to recruit 365 days a year, whether it’s a student-athlete or a student on campus. It’s a competitive market out there and you always have to be on the cutting edge.”

Just because a sports information director must now devote hours to webcasting and creating e-mail push products and regulating student-athlete blogs doesn’t mean they can abandon some of the traditional duties of sports information. For example, Nott at Grand Valley State said that he still has that editor at the small paper in the small town who seems averse to e-mail.

“You still need to fax stuff to him,” he said. “Just because the Web was created didn’t mean we could really get rid of anything.”

At Arizona State, Tammaro said his staff is trying to balance providing content for the public and the media. For example, he said, the media doesn’t want to listen to a podcast of a press conference — they want to read the quotes — so the sports information staff still transcribes the press conferences. But providing the audio for the general public has its advantages, too — the general fans can hear tones or inflections in the voice of a coach or student-athlete and judge context for themselves.

“You want to do all this new stuff, but you don’t want to get away from the stuff that the people you work with on a daily basis are using,” Tammaro said. “You basically get a lot more work, but some of it is kind of fun.”

Many sports information directors see the explosion of new media and the resulting expectations of the public as a mixed blessing. While it allows athletics departments in many cases to skip the middle man of mainstream media and take their stories and messages directly to the public, it has also created additional work.

Warwick said that new media has made the ultimate goals easier to reach.

“In one sense, it’s made for more work. It’s more work to prepare for a game when there’s going to be that kind of media coverage than it would be to prepare for a game that’s not going to be broadcast,” Warwick said. “By the same token, it’s made our jobs a little easier by making it easier to meet our goals. If our goal is to get information to as many people as possible, this is a way that just wouldn’t have been possible 10 years ago.”

At Grand Valley State, Nott said when the sports information professionals took over updating the athletics department Web site, it created more work for his staff, but it was also a watershed moment for the site.

“We were no longer relying on other people updating it. We’ve really taken initiative to make sure things get up there in a timely fashion,” he said. “It’s a lot more work because you’re doing it at home or you’re coming in late, but we’ve gotten a great response from our fans and they appreciate it. You kind of create your own monster. We felt it was something we needed to do.”

There’s no sign that the monster will need to be fed any less in the future. In fact, many sports information directors are contemplating forays into even more new media worlds.

Warwick said some things that seemed so foreign just two or three years ago are now staples in American life, like Internet radio and using the Web to widen the audience for intercollegiate athletics.

“It’s hard to imagine or predict how the changes that you know are coming in technology are going to give you chances and opportunities to do these kinds of things,” he said.

At Stevens Tech, Granata and the athletics department launched a complete redesign of the athletics Web site, www.stevensducks.com, earlier this month. “As a technology-based school, we feel that we should be at the forefront of new media. We added a lot of new features, things we don’t currently have,” he said. “Last year it was Duck Casts, this year it’s the new Web site. It’s going to be something new next year. We’re always trying to do something.”

Though the precursors to what we know today as the Internet were born in the late 1960s and early 1970s, use of the World Wide Web exploded after 1990 when restrictions on commercial use were lifted. The Internet carried audio and video for the first time in 1992. Today, the Internet, technology and its ever-expanding capabilities mean different things to different institutions and their athletics departments, depending on size, desire and capabilities.

For some institutions, technological advancements mean that even if a student-athlete’s parents live in California and the institution their son or daughter attends is in New York, those parents can still watch competition.

For other institutions, new media applications have allowed them to provide podcasts of press conferences or access to promotional television spots or even live chats with coaches and student-athletes.

Athletics departments make new media decisions based on what their audience demands — and what the institutions can afford to provide. But whether they are broadcasting every home game over the Internet or allowing a coach or athletics director to offer a few thoughts through a weekly blog, NCAA members are taking advantage of the opportunities the new media world is offering.

“The public wants everything you can give to them,” said Tim Nott, sports information director at Grand Valley State University. “In today’s society, that’s why newspapers break stories without having the right facts, because they can get beat out by the real time of the Internet. You can have it online instantly, and for a newspaper, you have to wait until tomorrow. Tomorrow’s no good anymore.”

At Arizona State University, Sports Information Director Doug Tammaro said he looks at the Sun Devils Web site as the athletics department newspaper. Where the sports information staff at Arizona State once competed with other area schools to get items into newspapers, now their Web sites compete with media juggernauts like ESPN.com and CBS Sportsline. They offer insider features the conglomerates don’t have access to — like the public service announcements about the Sun Devils athletics program or a collection of reproductions of billboards promoting an Arizona State athletics marketing campaign “Sun Devil Laws” that can be seen in person in the Phoenix area.

“You want to drive people to your Web site. It’s like your newspaper and your television station,” Tammaro said. “It’s a great way to get the word out about your team. You just have to have the people power to be able to do it.”

Use of campus resources

So how do you manage when you work on a staff with just two — or fewer — full-time sports information professionals? That is the life of most Division III and many Division II athletics department media relations offices.

Many institutions use their student population to help produce content for their athletics department Web sites. At Division III Ithaca College, the athletics department had a ready-made avenue for webcasting and broadcasting audio from competitions. With two campus radio stations and a campus television station broadcasting dozens of hours of live original programming per week, all three outlets were already actively covering athletics events. About seven or eight years ago, the stations began broadcasting through Ithaca’s Web site, a great service but one with limited availability. Eventually, the athletics department partnered with a company that could provide unlimited bandwidth and more technological capability that provides for unlimited audience potential.

Ithaca Sports Information Director Mike Warwick said it was beneficial to have two radio stations doing so many games, “but by that same token,” he said, “it kind of handcuffs us in that you can listen to all of our women’s basketball games, but you can’t listen to volleyball because they don’t choose to broadcast those. So we need to find ways to provide that kind of service to fans without having to rely on someone else on campus to actually provide it.

“It’s not because we’re not happy with (the campus stations) or we don’t appreciate it — they just can’t provide as much content as we want to be able to provide to our audience.”

To that end, more institutions like Ithaca are choosing to produce webcasts and audio broadcasts completely on their own, often with assistance from students from the institution’s communications program.

Stevens Institute of Technology launched its first full year of formal, branded webcasting with the 2006-07 academic year. Called “Duck Casts,” Warwick said the model is one he would like to emulate at Ithaca. Brian Granata, sports information director at Stevens Tech, said the Duck Casts are produced with a largely student-based staff. What started as a modest goal of producing about 30 webcasts quickly grew to 75 because of the demand.

Granata, who produced each event, trained several student producers to fill his role when he had to attend to other sports information duties. Students served as color and play-by-play announcers. They also did all the camerawork and provided graphics.

“It’s been challenging at times, but we have a talented student base that has latched on to this project,” Granata said. “It’s exciting.”

Meeting expectations

Even though the institutions might be smaller and less flush with cash than some of the larger Division I institutions, the expectations of the parents who send their children to play sports at a Division III school often are not lower than those who send their kids to a major Division I program. Warwick said that as technology has developed, people have begun to expect that certain things will be available to them.

“Because you’re dealing with parents of your student-athletes using this technology, they haven’t been parents of college athletes for 10 years like I’ve been SID for 10 years. They come into the role of being parents of college athletes and they see what technology is available, and they just expect to be able to listen to the game over the Internet,” Warwick said. “If they’re going to have that mindset, I’m glad we have the technology to be able to meet that expectation.”

Sometimes that expectation isn’t there, but institutions still can use technology to generate interest in their program among local and national audiences.

“I think at major Division I schools, there’s so much television and newspaper coverage, which brings on its own challenges, but the interest is already there and it’s going to feed itself,” Granata said. “At Division III, you’ve got to work to find new and creative outlets.”

The NCAA and its corporate partners first ventured into webcasting with “March Madness On Demand” in 2003. For the first time in 2006, March Madness On Demand provided free live streams of Division I men’s basketball tournament contests (it had been a pay service before 2006). On the heels of incredible popularity in 2006, CBS Sportsline doubled the bandwidth for the project, built a live updating scoreboard into the video player, increased the viewing screen and included live radio broadcasts for the entire tournament. The network even added a halftime show.

Balancing new and old media

People responded to the product: 46 percent of the 1,381,875 users for MMOD were new in 2007 and total hours of consumption were up 28 percent.

At institutions at all levels, the Web is seen as a new area in which institutions can recruit — both student-athletes and the general student population. Tim Match, sports information director at Clemson University, said the Web has created opportunities for instantaneous feedback from all sources — positive or negative.

“The Internet provided a tremendous amount of opportunities for us to promote Clemson, and when you have more opportunities, you have to take advantage of them,” Match said. “We try to recruit 365 days a year, whether it’s a student-athlete or a student on campus. It’s a competitive market out there and you always have to be on the cutting edge.”

Just because a sports information director must now devote hours to webcasting and creating e-mail push products and regulating student-athlete blogs doesn’t mean they can abandon some of the traditional duties of sports information. For example, Nott at Grand Valley State said that he still has that editor at the small paper in the small town who seems averse to e-mail.

“You still need to fax stuff to him,” he said. “Just because the Web was created didn’t mean we could really get rid of anything.”

At Arizona State, Tammaro said his staff is trying to balance providing content for the public and the media. For example, he said, the media doesn’t want to listen to a podcast of a press conference — they want to read the quotes — so the sports information staff still transcribes the press conferences. But providing the audio for the general public has its advantages, too — the general fans can hear tones or inflections in the voice of a coach or student-athlete and judge context for themselves.

“You want to do all this new stuff, but you don’t want to get away from the stuff that the people you work with on a daily basis are using,” Tammaro said. “You basically get a lot more work, but some of it is kind of fun.”

Many sports information directors see the explosion of new media and the resulting expectations of the public as a mixed blessing. While it allows athletics departments in many cases to skip the middle man of mainstream media and take their stories and messages directly to the public, it has also created additional work.

Warwick said that new media has made the ultimate goals easier to reach.

“In one sense, it’s made for more work. It’s more work to prepare for a game when there’s going to be that kind of media coverage than it would be to prepare for a game that’s not going to be broadcast,” Warwick said. “By the same token, it’s made our jobs a little easier by making it easier to meet our goals. If our goal is to get information to as many people as possible, this is a way that just wouldn’t have been possible 10 years ago.”

At Grand Valley State, Nott said when the sports information professionals took over updating the athletics department Web site, it created more work for his staff, but it was also a watershed moment for the site.

“We were no longer relying on other people updating it. We’ve really taken initiative to make sure things get up there in a timely fashion,” he said. “It’s a lot more work because you’re doing it at home or you’re coming in late, but we’ve gotten a great response from our fans and they appreciate it. You kind of create your own monster. We felt it was something we needed to do.”

There’s no sign that the monster will need to be fed any less in the future. In fact, many sports information directors are contemplating forays into even more new media worlds.

Warwick said some things that seemed so foreign just two or three years ago are now staples in American life, like Internet radio and using the Web to widen the audience for intercollegiate athletics.

“It’s hard to imagine or predict how the changes that you know are coming in technology are going to give you chances and opportunities to do these kinds of things,” he said.

At Stevens Tech, Granata and the athletics department launched a complete redesign of the athletics Web site, www.stevensducks.com, earlier this month. “As a technology-based school, we feel that we should be at the forefront of new media. We added a lot of new features, things we don’t currently have,” he said. “Last year it was Duck Casts, this year it’s the new Web site. It’s going to be something new next year. We’re always trying to do something.”

© 2010 The National Collegiate Athletic Association

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy